Early on a mid-December morning, back when gatherings indoors happened frequently, I drove to a church in the West Island of Montreal to join descendants of United Empire Loyalists, Orangemen, Irish army regulars and pro-Fenians.

Together, we listened in awe as Dr. Jane G. V. McGaughey, a professor from the Irish studies department at Concordia University talked about a battle that took place in November 1838 on the shores of the St. Lawrence River.1

Traditional historians usually ignore genealogists, but McGaughey, who integrated genealogy into her first book “Ulster’s Men,” treated us like the respected colleagues we are.

Her practice should be more widespread. Genealogists can be some of the most fervent history buffs out there, and historians can build strong platforms if they succeed in getting our attention.

We also help democratize history so that it includes everyday people instead of focussing primarily on elites. Most of my stories feature farmers, store-keepers, carpenters and other working class people.

Because family historians in Canada research specific individuals, we also get interested in the most minute details about small communities. We expose secrets within families. We bust long-held myths, reveal unusual settlement patterns and emphasize the roles of otherwise ignored individuals in societies. We help Canadians discover who they are.

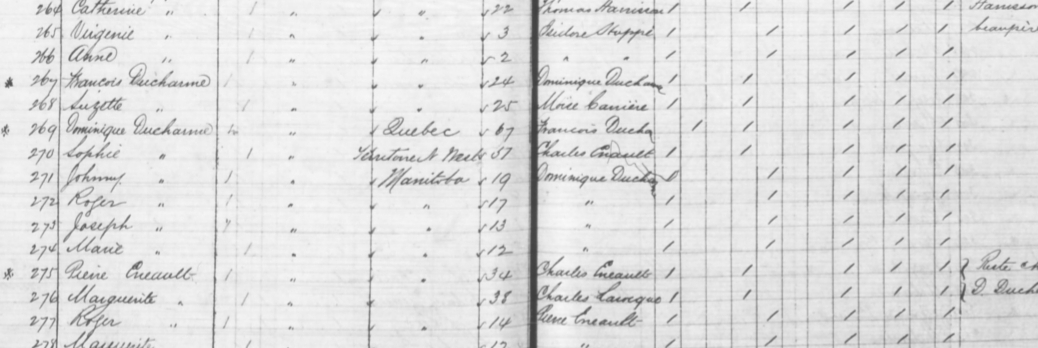

Sometimes, we discover reasons for tourists and visitors to stop by tiny hamlets that used to be important gathering centres. A story about my four-times great grandmother on my father’s side had me investigating a small community on the shores of the Seine River between Winnipeg, Manitoba and Grand Forks, North Dakota, for instance. Today, not many people notice the tiny place next to the Trans Canada and #12 highways, but it played many important roles in previous eras, as an Aboriginal village, a Catholic Mission and as a stopover on the Dawson Trail during the Red River Rebellion. The community was called Oak Point when Marie Sophie (Séraphie) Henault-Canada was born there in 1818. It became St. Anne by the time she died in the same town 74 years later. (Read my stories about Oak Point here and here.)

Researching the minute history of communities across the country can attract diverse audiences. Sharing such research at presentations and get-togethers can create entirely new memories and evolve our culture.

Researcher Monisha Pasupathi described the process in which adults develop individually and together to create a common culture for a paper in the Psychological Bulletin journal.

“…I have argued that talking about past experiences is a process by which our autobiographical memories are socially constructed. I proposed that talk about the past in conversation is coconstructed, and that subsequent memories for events talked about in conversation are likely to be consistent with that socially constructed version. Thus, the content of autobiographical memory is a result of both experiences and social reconstructions of those experiences. Later I suggested that conversing about past experiences both influences and can be influenced by adult development. Socially constructing the past may promote either continuity or change in identity across adulthood.”2

Academics frequently underestimate family historians. Archivist, researcher, and information science professor from the University of Michigan interviewed 29 specific genealogists in detail to discover what kinds of problems they try to solve. Her analysis determined that we are much more detail-oriented and meaning-seeking than she anticipated.

Genealogy and family history are examples of everyday life information seeking and provide a unique example of intensive and extensive use of libraries and archives over time. In spite of the ongoing nature of this activity, genealogists and family historians have rarely been the subject of study in the information seeking literature and therefore the nature of their information problems have not been explored. This article discusses findings from a qualitative study based on twenty-nine in-depth, semi-structured interviews with genealogists and family historians and observations of their personal information management practices. Results indicated that the search for factual information often led to one for orienting information. Finding ancestors in the past was also a means of finding one’s own identity in the present. Family history is also an activity without a clear end goal; after the ancestry chart is filled in the search continues for more information about the lives of one’s forebears. Thus, family history should be viewed as an ongoing process of seeking meaning. The ultimate need is not a fact or date, but to create a larger narrative, connect with others in the past and in the present, and to find coherence in one’s own life.3

Genealogists often work from home, which is why we pay to access historical data.

Some academics worry that the partnership between genealogists and corporations like Family Search and Ancestry emphasize religious or corporate goals over historical accuracy, but those issues stem from consumer-oriented cultures, not from the practice of genealogy itself. Public institutions in France and Quebec have created impressive databanks without the help of religious or private organizations. As public education cuts funding to historical research centres, genealogists have enabled archives, foundations and libraries to collect and protect documents that would otherwise be destroyed.

The people in the room listening to McGaughey were typical of every genealogical presentation I’ve attended. We all represented different sides of a feud going back generations and emotions ran high. Not because we were angry at the others or sought to heal an ancient misjustice. A genealogy presentation is the one place where diversity isn’t just tolerated, it’s sought out. With diverse researchers, the chance of learning about new sources, techniques and ideas grows exponentially. Our excitement came from the possibility that someone might share an important detail that would help us better document an ancestor’s life.

That’s the key difference between family historians and most of our academic cousins. We concentrate on the lives of specific people rather than significant issues or eras. Social historians and those who focus on biography are not so different from genealogists. We too are learning to source digital, secondary and derivative records properly, seek accreditation for the quality of our analyses, and write narrative nonfiction in compelling ways.

Our work certainly reaches a lot of people in word-of-mouth ways. A few years ago, I prepared a mini genealogical report as a gift for my great-aunt’s 96th birthday. The report garnered more attention from the teens and young adults in the family who had never heard of genealogy. They had lots of questions about the small Ontario town in which she was born, the Edmonton home she lived in during her teens and the kind of work she did during World War II. I knew the conversation connected them to their ancestors, when one of the young people told me that “these sound like real people.”

Feminist researchers might consider collaborating with genealogists. In my experience, most genealogists are women, and we have a lot of trouble finding good sources of information to find our female ancestors. Perhaps by linking family historians with academic historians, we could reduce the level of gender bias in historical narrative over time.

So often, the stories we hear about the past are myths made up of half-truths. Academic and family historians can partner to co-create new stories to captivate all Canadians.

1McGaughey Dr. Jane G. V., Family Ghosts: When Personal History and Professional Research Collide, presentation for the Quebec Family History Society, Briarwood Presbyterian Church Hall, Saturday, December 14, 2013, 10h30.

2 Pasupathi, Monisha. The social construction of the personal past and its implication for adult development. Psychological bulletin 127, 2001, p 664.

3 Yakel, Elizabeth, Seeking Information, Seeking Connections, Seeking Meaning: Genealogists and Family Historians, Information Research: An International Electronic Journal, v10 n1 Oct 2004.