A strange clomp, clomp, clomping woke me up. I looked around a strange room, from a strange bed, in a strange country. It was 1973 and I had arrived in West Germany the day before on a Canadian German Academic Exchange Society trip. I was going to a farm to work for two months, but the only location I had was Hofgut Dorntal. I knew it was in West Germany, but I had no idea where.

The clomping was the farmer, Herr Leo Knorzer going downstairs on his artificial leg. I assumed he lost it during the war and never asked him about it. It turned out it was in a car accident. His leg was broken and the cast was put on too tight. By the time his brother, a doctor visited, gangrene had set in and the leg couldn’t be saved.

I had just finished my third year at Queens University in Kingston Ontario. I had taken German as an elective, although majoring in biology. One day, the professor announced that we should all apply for a summer exchange in Germany, so I thought, why not! We could apply to study or to work. I didn’t expect to be chosen but when another student dropped out, I was offered a place.

We flew to Frankfort and picked up train tickets to our final destinations. My ticket said Eubigheim. I boarded a train to Munich, but had to change in Lauda. I sat alone on a bench outside the Lauda station in the cold and wet, thinking I would rather be home! I When the Eubigheim train arrived, it was only a two-car commuter train. All the seats were full, so I sat on my suitcase. I hadn’t slept, so I dozed as the train rumbled on. I kept jolting awake, hearing strange words around me. I knew they were German but some sounded like out-of-context English. I had to keep alert so I wouldn’t miss my station.

When we arrived at Eubigheim, I gathered my luggage and followed the commuters off the train. They hurried through an empty station and out the other side. With no one to ask, I wandered around outside the station and found a man in a little office. With some difficulty, I made him understand that I wanted to contact Herr Leo Knorzer at Hofgut Dorntal. He called and soon their son arrived in his little Porsche sports car. I was expected, but not that day. His parents were out at a farmer’s meeting. Ekkehard spoke good English but said this was the only time he would speak English, as I needed to learn German to communicate with his parents.

Ekkehard and his wife Gutrune had their own apartment in his parents’ house. Gutrune was expecting a baby, so they needed help with the chickens. They gave me supper of rye bread, cheese and salami while we watched Bugs Bunny cartoons on TV in German. What was I doing there! They showed me to my room on the other side of the house and I slept, to be awoken by the clomping. I had forgotten the alarm clock I had purchased for the trip, so Frau Knorzer had to wake me with a knock on my door.

My main job was collecting eggs. They had a large barn with two sections of hens. One section, the horse stalls, was up steep cement steps where I collected the eggs by hand into buckets and carried them down. I always worried about falling down the stairs with all the eggs! The other section was on the ground floor and automated. They had conveyor belts which carried the eggs into the grading room where they would be sorted by size and weight. Any dirty eggs had to be washed and misshapen eggs broken into a bucket. Those eggs were frozen sent to make egg noodles. The conveyor belt worked well until an egg broke. Then, with the call gelbe, gelbe (yellow, yellow) the conveyor was stopped and Herr Knorzer had to go into the hen house and clean it up so not all the eggs would need to be washed.

Conveyor belts under the cages carried away the poop and others supplied food. Pipes carried their water and the dispensers often leaked.

“ Today I washed all the egg racks and pails. Then I swept and removed cobwebs in the cellar. Then I washed the whole wash kitchen. When I collected the eggs there was water dripping. One of taps was gone and the feeding tray was full of water. I held my fingure over the hole while Gurtrune tried to block it. Then I carried out the wet feed.”

Most hens lay an egg a day. When their production falls, they are crated and sent away. That was tough work as the hens didn’t cooperate, resulting in scratched and pecked hands. The Knorzers didn’t raise hens from chicks but would buy a new set of laying hens.

“ The new hens came today, all 2000 of them. The men came at 7 am. What a stinking mess. Shit all over the place from the frightened birds. I took out the birds while Frau K. put them in cages. I got more bruises on my poor arm.”

These new hens laid lots of eggs. One morning I collected 3261 eggs or 27 pails full that all had to be carried down the stairs.

Most evenings, Frau Knozer would deliver the eggs to customers. So Herr Knorzer and I often ate, just the two of us. He was very interested in how everything worked in Canada: farms, hospitals, schools and transportation. With my rudimentary German and his only English words, grandfather and grandmother one would think we would have trouble communicating but he could always find another way to say something so I would understand. Because of his patience, I learned quite a bit of German.

Frau Knorzer, on the other hand, had no patience. She would get very frustrated when I didn’t understand what she wanted me to do. “Die Mary this and die Mary that!” she would say with a sigh. She did everything quickly but one vacuumed slowly. She always told me, “Immer langsam.” I still hear her, “always slowly,” every time I vacuum. I did learn to clean the house to her satisfaction and weed the garden while only pulling out some of the lettuce.

The farm was a few miles from anywhere, so at night we would just watch TV. They took me most places they went, including to their next farmers’ meeting. We walked into a room with about twenty people sitting around a large table. They introduced me, and I had to walk around and shake everyone’s hands. They treated me as one of the family so much so that after their two daughters and their families left after a visit, Frau Knorzer said she was tired of entertaining them and glad it was just us!

“My last day wasn’t a good day. Overnight visitors came and I am sleeping on a lawn chair in the sewing room. After the eggs, I had to clean out my room, help change the beds, vacuuum, make a cake with 20 minutes beating sugar and eggs, clean Soren’s room, clean up the kitchen, sweep, then lunch, clean the car, wash the floors and then I was finished!”

I left at the end of July after two months of work. I then had a month to travel before meeting up with my exchange group in Frankfurt for a trip to Berlin, before we flew home. I left the farm without any real plans. The Knorzers said that if I had any problems or for any reason, I was welcome to come back. They drove me to Osterburken, where I boarded a train to Heidleburg on my way to Frankfurt to begin another adventure.

My parents didn’t know where I was going or even if I had arrived. I sent a postcard soon after I arrived.

“ I got 2 letters today. One from Mom and one from Dad. They just got my postcard on the 27th. That took over a month to get there. I think they were kind of worried.”

Notes:

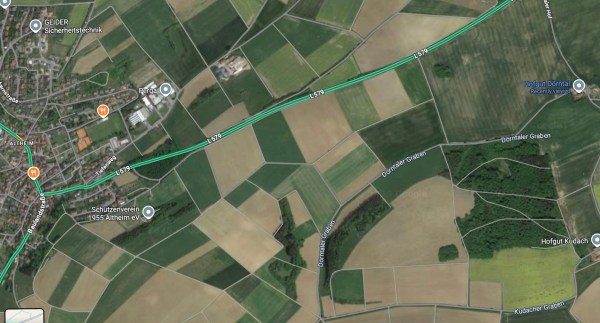

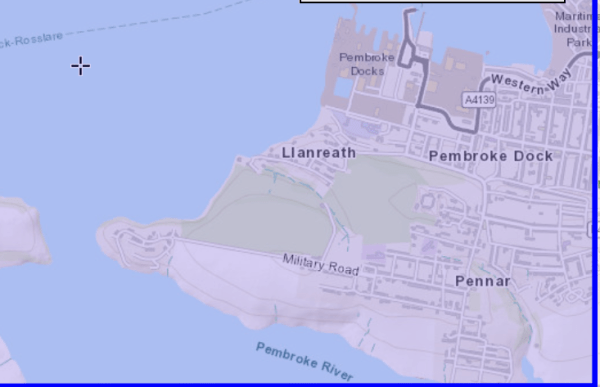

Fast forward to 2026. I Googled Hofgut Dorntal and Google Maps took me right to the farm. I could see the house and the outer buildings.

I also couldn’t find Eubigheim, but when I Googled Altheim, the town nearby, Eubigheim appeared on the map, right on a railway line. It was the closest station to the farm, but not the most convenient. There is a three-story building where the Banhof should be, but on the side of the building is a big sign “Eubigheim,” so it appears that it is the station.

All the quotes are from a journal I kept during the summer of 1973.

I looked up Leo and Erna Knorzer on the internet and found their final resting places.

Gravsten: Friedhof Osterburken (Neckar-Odenwald-Kreis) Germany.

Knorzer Erna Hofmann 1922-2007. Knorzer Leo 1911-2006.

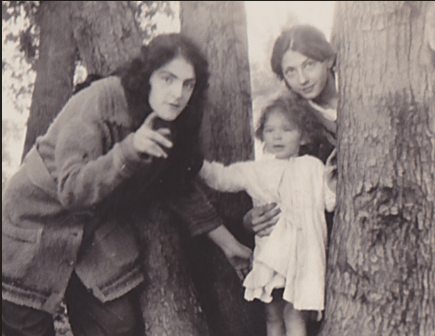

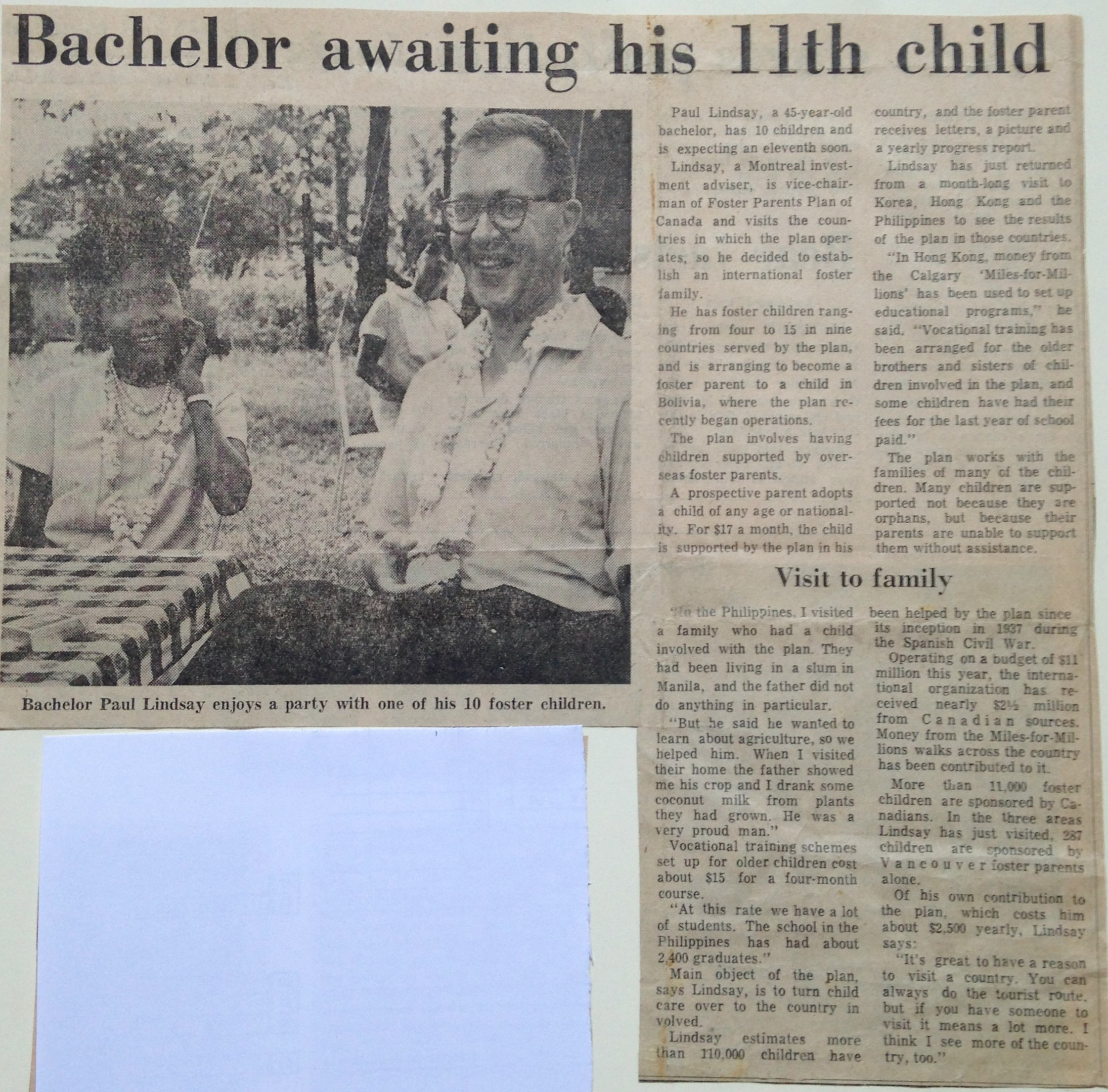

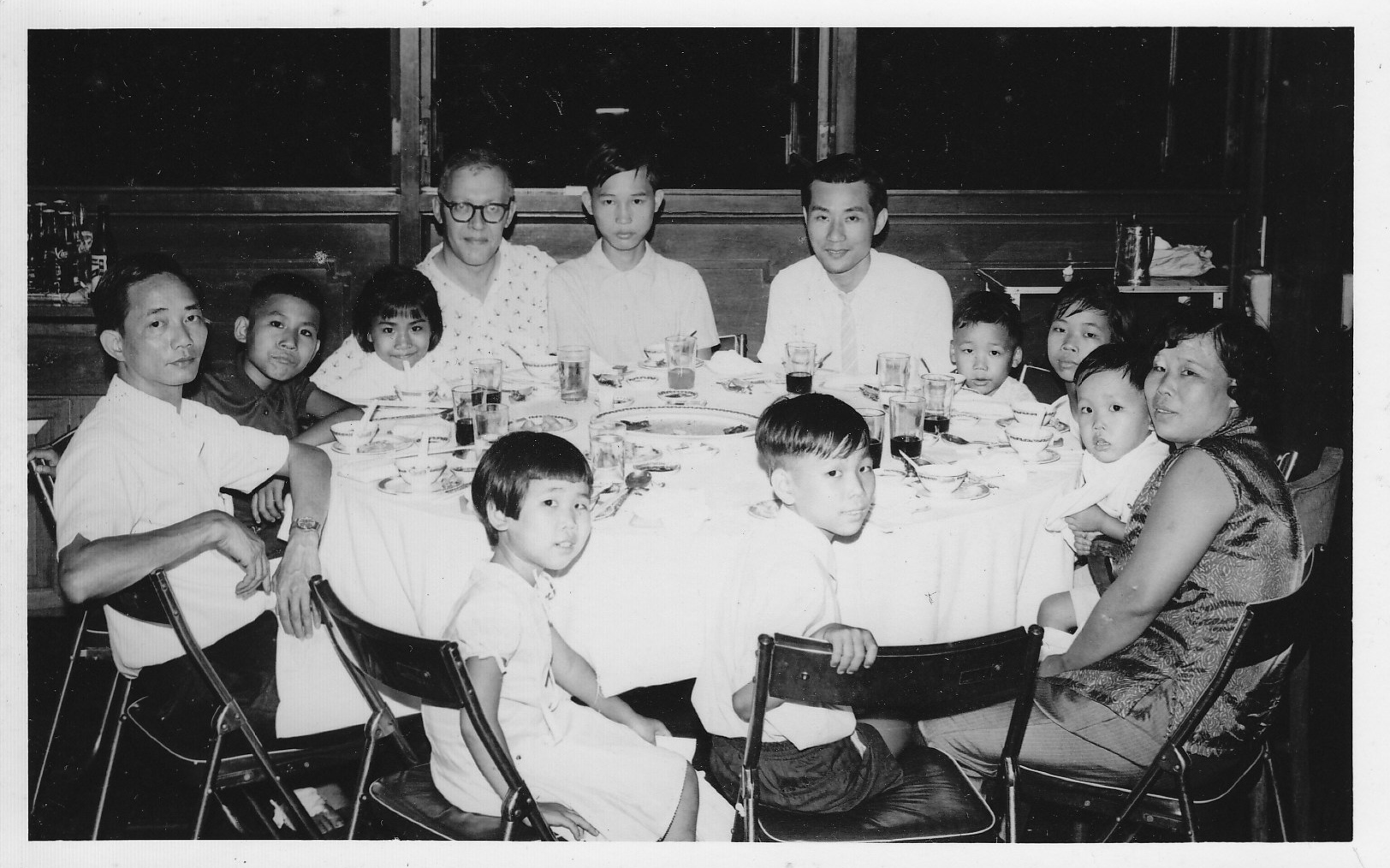

1969 – Uncle Paul travels internationally to visit his foster children.

1969 – Uncle Paul travels internationally to visit his foster children. Uncle Paul with some of his foster children and their family.

Uncle Paul with some of his foster children and their family.

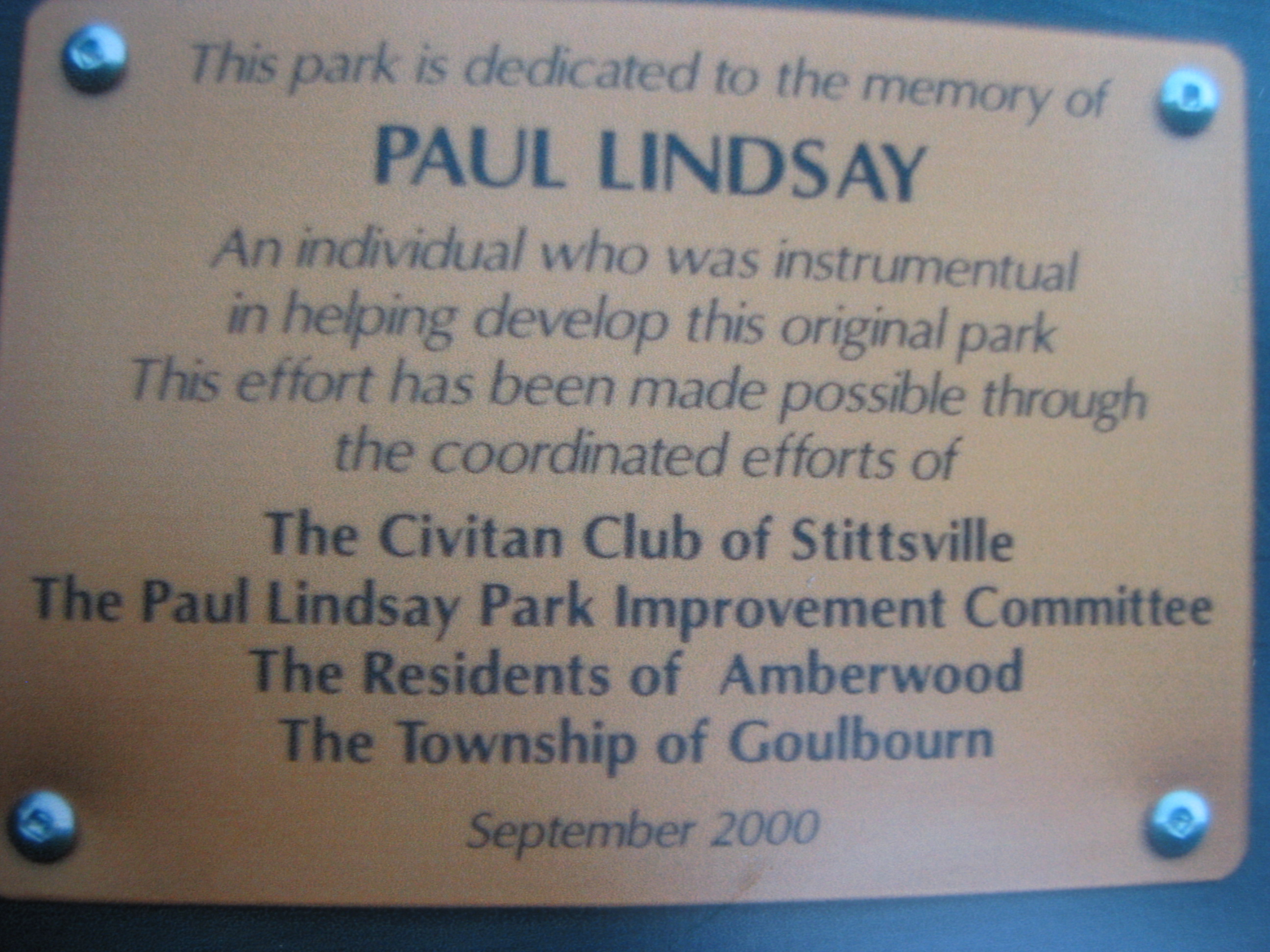

Paul Lindsay Park Dedication

Paul Lindsay Park Dedication Uncle Paul’s Nieces, Nephews and Family – May 2018

Uncle Paul’s Nieces, Nephews and Family – May 2018 Paul Sydenham Hanington Lindsay (1923-1987)

Paul Sydenham Hanington Lindsay (1923-1987)