In collaboration with Justin Bur

When my great-great grandfather Stanley Clark Bagg died in 1873, his wife and five children inherited large tracts of farmland on the island of Montreal, land that they made a family business of selling.1 But misunderstandings over who owned what and how to keep track of the income created a lot of difficulties.

Stanley Clark Bagg (I usually refer to him as SCB to differentiate him from his father, Stanley Bagg, and his son, Robert Stanley Bagg,) had inherited most of this property from his grandfather John Clark (1767-1827).2 But there were conditions attached to some of these bequests: Clark’s 1825 will stated that land that comprised the Durham House property, and land comprising Mile End Farm, should pass down through three generations of descendants before it could be sold. The legal term for this, in civil law, is a substitution. However, a change in the law, passed in 1866, limited substitutions to two generations.3 That meant that the generation of Robert Stanley Bagg and his sisters Katharine, Amelia, Mary and Helen were the last generation affected by the substitutions and they could do what they liked with these properties.

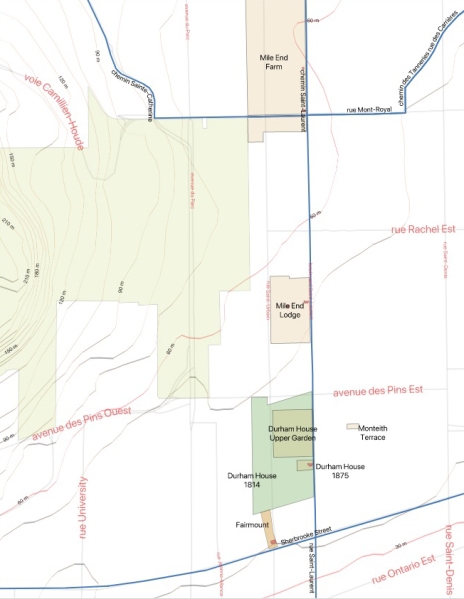

The substitution clause referring to Durham House was part of the 1819 marriage contract between SCB’s parents, in which John Clark gave that property to his daughter as a wedding present.4 (It is shown in dark green on the map below.)

When SCB died at age 53, none of his family members was ready to manage these properties. His only son, Robert Stanley Bagg, or RSB, (1848-1912) had recently graduated in law, but he had no experience in renting or selling properties. Furthermore, neither the notary who completed the inventory of SCB’s estate in 1875,5 nor SCB’s widow, nor his children were aware of the substitutions. The Durham House and Mile End Farm properties were treated as though they were no different than the other properties belonging to the late SCB’s estate.

The 22-acre Durham House property (lots 19–28 and 101–115, cadastre of the Saint-Laurent ward) was located north of Sherbrooke Street, on the west side of today’s Saint-Laurent Boulevard. SCB had subdivided part of it and sold lots from it as early as 1846. In 1889, RSB, who was an executor of his father’s estate, subdivided the Upper Garden of Durham House (lot 19, Saint-Laurent ward) and began to sell those lots. He signed the property documents as “R. Stanley Bagg for the estate,” and his mother, Catharine Mitcheson Bagg, also signed.

But the Durham House property actually belonged jointly to the five Bagg siblings. It was not part of SCB’s estate, and his widow could not inherit this land, sell lots from it or acquire income from it. Yet that is what she did: the name Dame Catharine Mitcheson, widow of Stanley Clark Bagg, appeared on five deeds of sale in 1889.

It is not clear who discovered the error, but perhaps someone close to the Bagg family took a good look at the property documents and noticed these details. SCB’s middle daughter, Amelia Bagg, was to marry Joseph Mulholland the following year, and he worked as a real estate agent for the Stanley Clark Bagg Estate. Also, Joseph’s brother-in-law, John Murray Smith, was about to purchase several of the Durham House lots. Any one of these people could have discovered the marriage contract and John Clark’s will, which SCB had registered at the provincial land registry office.6

As soon as they became aware of the situation, the Bagg siblings tried to remedy it with a notarized document called a Ratification.7 It said that, as the actual owners, they ratified and approved the five sales made by their mother. A few weeks later, in January and April of 1890, the Bagg siblings sold five lots to John Murray Smith and four to James Baxter, and this time, the vendors named in the deeds were correct.

Next, Catharine and her five children took a step to sort out the income from lots from the Durham House property that SCB had sold in his lifetime. They did not involve a notary, but tried to look after the issue as a family, signing a document called an Indenture on May 12, 1890.8

The indenture stated that neither Catharine nor her children had known about the marriage contract until December, 1889. The Bagg children (by now all were adults) declared the love and affection they had for their mother and their desire to settle the matter amicably, and released her from all claims and demands. For her part, Catharine agreed to repay to her children the capital sums she had received from the sale of these properties. Because she had paid taxes and expenses on them, the children made no claim for the interest payments she had received.

Action Demanded

No doubt confident that everything had been resolved, RSB took his wife and two young daughters on an extended trip to England, leaving his mother and sisters to handle offers for land sales during his absence. After his return, however, the family dispute blew up once more, this time over the Mile End Farm property. Two of the married sisters, Katharine Sophia Mills and Mary Heloise Lindsay, hired a notary to represent their interests.

Notary Henry Fry sent a complaint on their behalf to the three living executors of SCB’s will — Catharine Mitcheson Bagg, Robert Stanley Bagg and notary J.E.O. Labadie – demanding immediate action. Dated July 22, 1891 and titled Signification and Demand,9 this document stated that the executors of SCB’s will were bound, upon his death, to deliver over the Durham House and Mile End Farm properties to his children, and to produce an account of the administration of these properties.

It stated that the executors “have wholly failed and neglected to render such account, but on the contrary, have, since the death of the said Stanley Clark Bagg, continued in possession of the said substituted property and have even sold and alienated portions thereof and have received the consideration money of such sales and have received and retained the entire revenues therefrom and that although they have been recently requested to render such account, the said executors have neglected and refused to do so.”

The executors had until August 10 to provide an account of the property belonging to the substitutions. They must have met this demand because no further complaints have turned up. Furthermore, the Bagg siblings seem to have found a better solution to their dilemma: they partitioned the Durham House property and sold a large chunk of the Mile End Farm.

In September 1891, the remaining unsold lots of the Durham House property were grouped into five batches, and the five siblings pulled numbers out of a hat to determine who got which ones.10 They could then sell these lots, or keep them, as they pleased.

Two months later, the five siblings sold 145 arpents of land, including most of the Mile End Farm and a section of the adjoining Black Gate Farm, to Clarence James McCuaig and Rienzi Athel Mainwaring,11 These Toronto land developers had plans to develop an exclusive housing development they called Montreal Annex in the area.12

As for keeping track of property sales, Amelia, the middle Bagg sibling who was now married to Joseph Mulholland, took on that responsibility. Starting in 1892, she kept a ledger in which she wrote down the dates, names of purchasers and prices paid for each of the lots that were part of the Mile End Farm and Durham House properties.13

This article is also posted on my personal family history blog, www.writinguptheancestors.ca

See also:

Janice Hamilton, “Bagg Family Dispute Part 1: Stanley Clark Bagg’s Estate”, Writing Up the Ancestors, Dec. 13, 2023, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2023/12/bagg-family-dispute-part-1-stanley-clark-baggs-estate.html

Janice Hamilton, “Aunt Amelia’s Ledger” Writing Up the Ancestors, April 26, 2023, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2023/04/aunt-amelias-ledger.html

Janice Hamilton, “Stanley Clark Bagg’s Family”, Writing Up the Ancestors, Feb. 29, 2020, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2020/02/stanley-clark-baggs-family.html

Janice Hamilton, “My Great-Great Aunts, Montreal Real-Estate Developers”, Writing Up the Ancestors, October 11, 2017, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2017/10/my-great-great-great-aunts-montreal.html

Janice Hamilton, “A Home Well Lived In”, Writing Up the Ancestors, Jan. 21, 2014, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2014/01/a-home-well-lived-in.html

Notes:

The Indenture, the Deed of Ratification and several other documents mentioned in this article were donated to the archives of the McCord Stewart Museum in Montreal around 1975 by my cousin.

This article was written in collaboration with urban historian Justin Bur. Justin has done a great deal of historical research on the Mile End neighbourhood of Montreal (around Saint-Laurent Blvd. and Mount Royal Ave.) and is a longtime member of the Mile End Memories/Memoire du Mile-End community history group (http://memoire.mile-end.qc.ca/en/). He is one of the authors of Dictionnaire historique du Plateau Mont-Royal (Montreal, Éditions Écosociété, 2017), along with Yves Desjardins, Jean-Claude Robert, Bernard Vallée and Joshua Wolfe. His most recent article about the Bagg family is La famille Bagg et le Mile End, published in Bulletin de la Société d’histoire du Plateau-Mont-Royal, Vol. 18, no. 3, Automne 2023.

Sources:

- Stanley Clark Bagg will, J.A. Labadie, n.p. no 15635, 7 July 1866

- John Clark will, Henry Griffin, n.p. no 5989, 29 August 1825

- In 1866 the government of Lower Canada enacted the Civil Code. This was a compilation and revision of the civil law inherited from the French regime; article 932 of the code put a two-generation limit on substitutions.

- Marriage contract between Stanley Bagg and Mary Ann Clark, N.B. Doucet, n.p. no 6489, 5 August 1819

- Stanley Clark Bagg inventory, J.A. Labadie, n.p. no 16733, 7 June 1875

- John Clark’s will and the marriage contract between Stanley Bagg and Mary Ann Clark are still publicly available at the Registre foncier du Québec. John Clark’s will had been transcribed there in 1844 (Montréal ancien #4752). The marriage contract (Montréal Ouest #66032) was transcribed in 1872. SCB’s will was transcribed into the register (Montréal Ouest #74545) in 1873.

- Deed of Ratification, Adolphe Labadie, n.p. no 2063, December 12, 1889, register Montreal Est #25109, McCord Stewart Museum (P070/66,3) This notary was a son of notary J.E.O. Labadie, who was an executor of the will, and grandson of notary J.A. Labadie, who had handled SCB’s will and the inventory of his estate.

- Indenture, May 12, 1890, McCord Stewart Museum (P070/B6,3).

- Signification and Demand, Henry Fry, n.p. no. 2234, 22 July 1891, McCord Stewart Museum (P070/B6,3).

- Deed of Partition, John Fair, n.p no 3100, Sept. 10, 1891, register Montreal Est #29503, McCord Stewart Museum (P070/B8,4).

- Deed of Sale, William de Montmollin Marler, n.p. #17571, 20 November, 1891, register Hochelaga-Jacques-Cartier #40225

- Justin Bur, Yves Desjardins, Jean-Claude Robert, Bernard Vallée, Joshua Wolfe, Dictionnaire historique du Plateau Mont-Royal (Montreal, Éditions Écosociété, 2017), p 271.

- Amelia Josephine Bagg Mulholland, Grand livre, 1891-1927, McCord Museum, Fonds Bagg, P070/B07,1. https://collections.musee-mccord-stewart.ca/en/objects/293626/a-j-mulholland-ledger (accessed April 3, 2023)

Among the more than 1100 gravestones and several hundred more unmarked graves in this cemetery, I was looking for the resting places of three of my direct ancestors: my six-times great-grandfather Daniel Bagg, his father-in-law, Isaac Phelps, and his son’s father-in-law, Consider Moseley. I found them in the southeast section of the cemetery where many of the oldest plots are located.1

Among the more than 1100 gravestones and several hundred more unmarked graves in this cemetery, I was looking for the resting places of three of my direct ancestors: my six-times great-grandfather Daniel Bagg, his father-in-law, Isaac Phelps, and his son’s father-in-law, Consider Moseley. I found them in the southeast section of the cemetery where many of the oldest plots are located.1

Lieut. Consider Moseley’s red sandstone tombstone, with a carved face, crown and wings symbolizing everlasting life, was close to Isaac’s.5 Consider (1675-1755) was the fifth of 10 children of John Maudsley (the name was spelled various ways) and Mary Newberry. The Maudsley/Moseley family moved from Windsor to Westfield around the time of Consider’s birth. In 1709, when Consider was 34 years old, he married Elizabeth Bancroft. They had eight children, including twins Elizabeth and Daniel, born in 1714. After his first wife died, Consider married widow Rebecca Dewey. His daughter Elizabeth married David Bagg, the son of Daniel Bagg and Hannah Phelps, in 1739.

Lieut. Consider Moseley’s red sandstone tombstone, with a carved face, crown and wings symbolizing everlasting life, was close to Isaac’s.5 Consider (1675-1755) was the fifth of 10 children of John Maudsley (the name was spelled various ways) and Mary Newberry. The Maudsley/Moseley family moved from Windsor to Westfield around the time of Consider’s birth. In 1709, when Consider was 34 years old, he married Elizabeth Bancroft. They had eight children, including twins Elizabeth and Daniel, born in 1714. After his first wife died, Consider married widow Rebecca Dewey. His daughter Elizabeth married David Bagg, the son of Daniel Bagg and Hannah Phelps, in 1739.