On a recent family trip to Cork, Ireland, we detoured briefly looking for the Anglin Family farmhouse ruins from the early 1800’s. Several Anglin cousins over the years recorded and shared their trips so that with copious precious notes in hand we thought we were well equipped for our adventure!

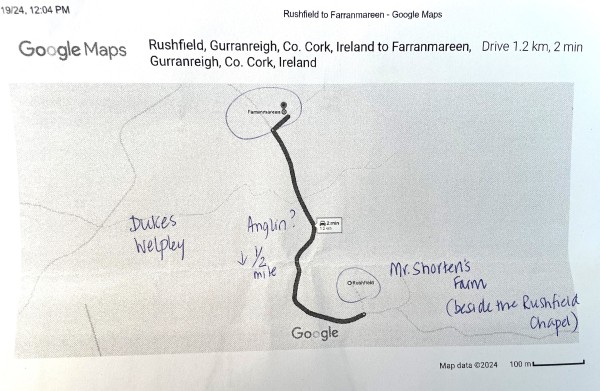

An Anglin letter from 1963 pinpointed the location of the family home somewhere between Farranmareen in the north and Rushfield (one kilometre further south) “near Bandon” just 36 kilometres west of Cork. We looked up the two geographic latitude and longitude (GPS) coordinates for the two markers so … how hard could it be?

All eyes were focused left and right as we drove the kilometre between the two points. Alas! Nothing to see but green fields everywhere and a scattering of houses. Where were the signs with “The Anglin Farm was HERE”?

Upon reaching Rushfield, my notes referred to a chapel not far from a farmhouse on the corner. Spying a farmhouse nearby, we made our way through the barking dogs and knocked on the door, but no one answered. We persevered as there was a vehicle in the driveway and a huge transport truck parked nearby. Another knock. Suddenly a farmer walked around from the side of the house munching on a bit of lunch.

I introduced myself as an Anglin and referred to the cousins over the years who had made the same pilgrimage. The farmer looked puzzled. So I inquired about the whereabouts of the Rushfield Chapel to which in reply he pointed to some ruins across the road that barely even looked like a building anymore. Disappointed but refusing to give up, I checked my notes and inquired if he knew a Mr. Shorten who was helpful to my cousin in 1963. He smiled and introduced himself as … Mr. Shorten!

Rushfield Chapel ruins

This Mr. Shorten didn’t recognize the Anglin name (it must have been his father in 1963) but guessed where the Anglin farm might have been. Back up the road to Farranmarren we drove to knock on a few more doors. The next stop was a bungalow with another barking dog. A middle-aged lady came to the end of the drive and thought the Anglin farm might have been in the field beside her. However, she suggested that her elderly neighbour across the road might know more and brought me to meet her.

“Looking for the farm some years ago, with my wife and two Anglin cousins, we could not find any buildings. But we knocked on a door at a corner where you leave the main road. The door was answered by an older lady whose maiden name turned out to be Duke. She gave us tea and said that our Anglin ancestors operated mixed farming and would have been comfortable during the famine.” (Perry Anglin)

After a brief introduction, I couldn’t resist asking her: “Is your maiden name ‘Duke’ by any chance?” Well her eyes lit up and she smiled saying: “Yes!” My great great grandfather William’s oldest brother John Anglin married Sarah Duke in 1836 in Cork. I was speaking with my (very) distant cousin!

William and John’s parents, Robert Anglin and Sarah Whelpley, had four sons and one daughter. All four sons emigrated to Kingston, Ontario, one by one, with my great great grandfather William (the youngest son) leaving Ireland in 1843 just before the Great Famine. John eventually joined the others in Kingston but only after the death of their parents. Their sister emigrated to the States possibly not wanting to stop in Kingston to care for four brothers!

William married Mary Gardiner in 1847 in Kingston and had two daughters (both died young) and two sons (William and James) who both became doctors and surgeons.

It appears likely that over the years Mother Nature reclaimed the Anglin Family farm with its defining stone walls having disappeared completely beneath the greenery. However, I can attest to the fact that the view described by my cousin remains the same:

“It is a stunning view from the farm down into the Bandon River and beyond to a coastal range tinted mauve in the distance.”

I would like to finish my little story by sharing some helpful information with my Anglin cousins! Here are the GPS coordinates of the Anglin Family farm: 51°47’00.3″N 8°56’09.8″W

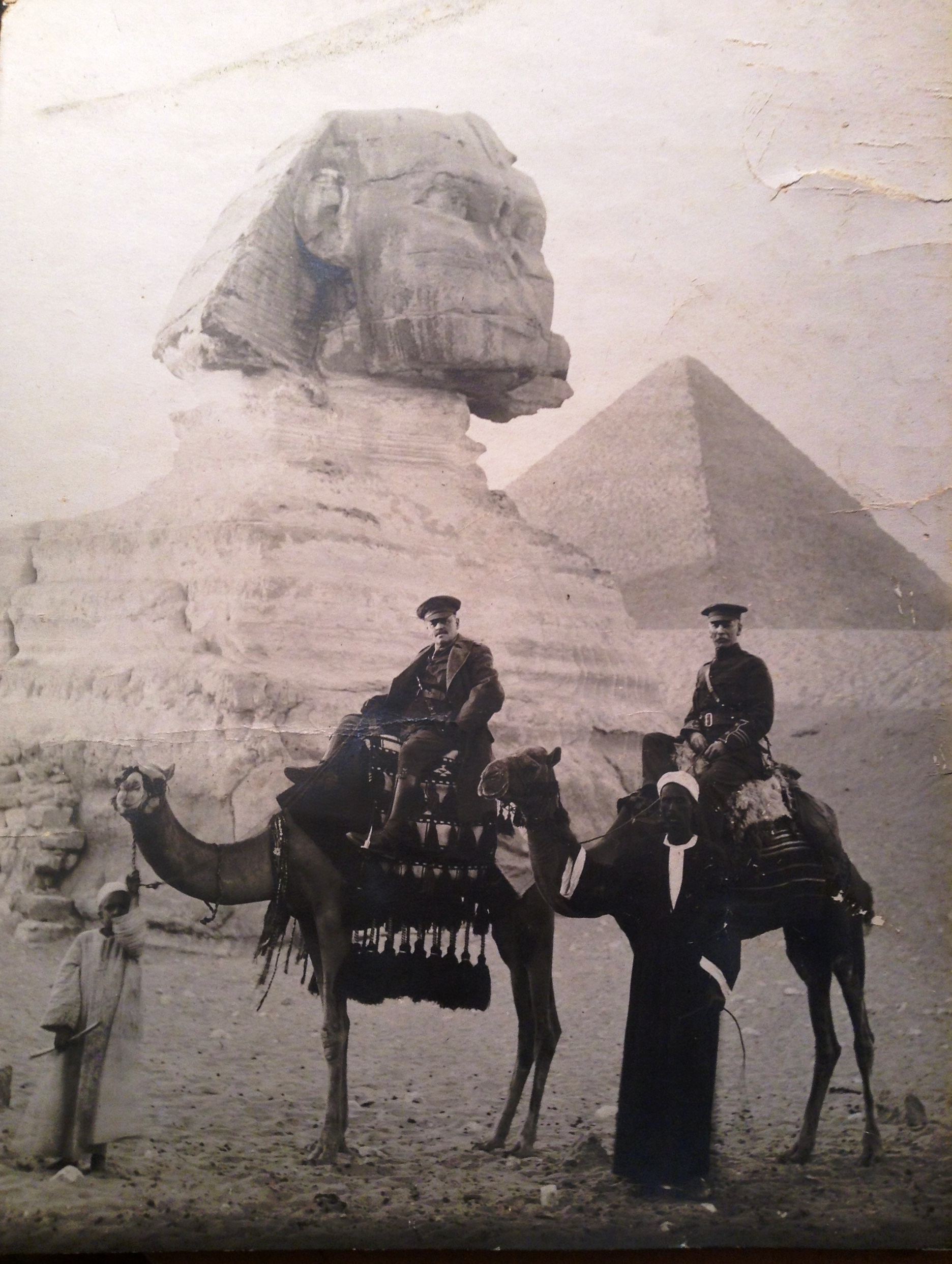

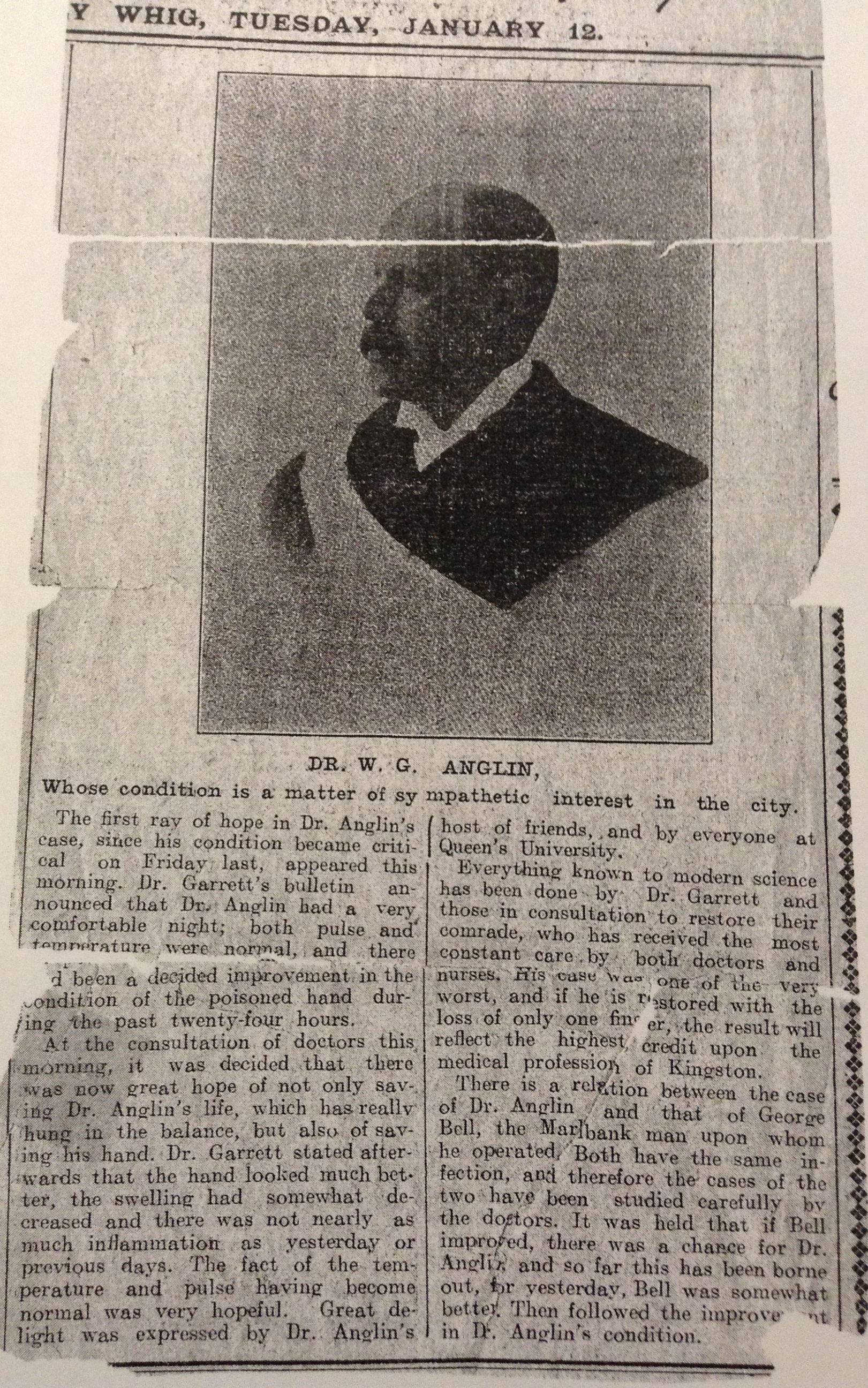

He served as a civil-surgeon with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel until 1916 when he became ill with Malta fever and phlebitis. He was given a medical discharge and sent back home.

He served as a civil-surgeon with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel until 1916 when he became ill with Malta fever and phlebitis. He was given a medical discharge and sent back home. The story told was that by using his “thought-reading” skills, he was able to physically draw down the infection in his right arm to his middle finger. The amputation of that one finger removed all traces of infection from his body probably saving his life… and enabling him to continue his work as a surgeon.

The story told was that by using his “thought-reading” skills, he was able to physically draw down the infection in his right arm to his middle finger. The amputation of that one finger removed all traces of infection from his body probably saving his life… and enabling him to continue his work as a surgeon.