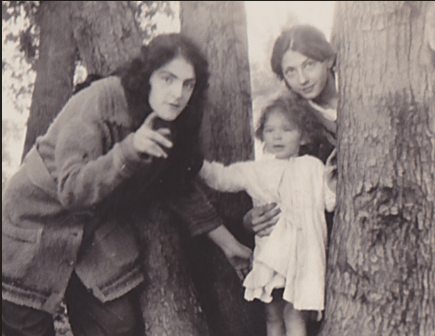

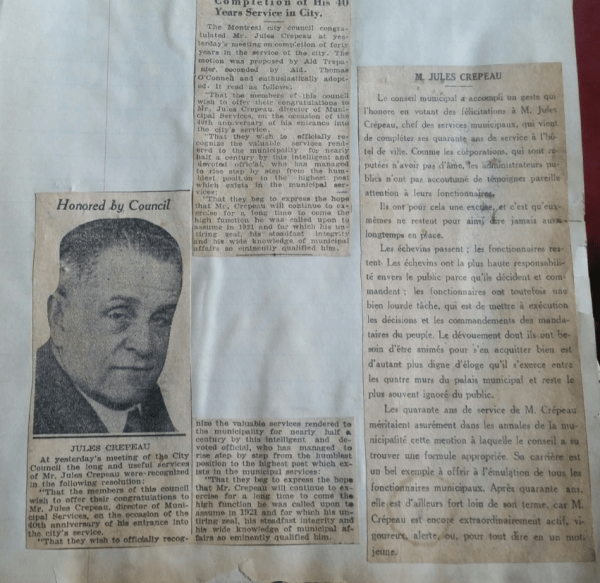

My mom liked to tell me that her father, Jules Crepeau, started work at eight years old in the 1880’s sweeping the floors at Montreal City Hall and that by the Roarin’ Twenties he had risen to be the highest paid civil servant in the city.

This family myth spoke volumes to me: my grandfather was a self-made man and a man of the very highest calibre.

By 1921, when my mother was born, Jules was Director of City Services responsible for just about everything that came down in the city, from the Prince of Wales’ official visits to damage control during typhoid epidemics to the handing out of liquor licenses in the Prohibition Era

All seven city departments were under his control, including and most significantly, the Police Department. My mother said that my grandfather occasionally brought her to work at City Hall. This must have made quite a huge impression on her.

My grandfather’s City Hall file reveals that he started out young as an intern in the city Health Department in 1888 and by 1901 he had worked his way up to the position of Second Assistant City Clerk, * aka the person who sees all the paperwork that passes though City Hall.

Jules had complete recall so this was a useful learning experience. In 1921, he landed that plum post of Director of City Services, a new position set up specifically to ensure an even distribution of municipal assets across the wards. Before the post was created, community groups from across the spectrum were invited to give their input on the subject.

I have since learned that Montreal’s burgeoning Greek community most probably had a hand in his promotion.1

A few years after my mom died in 2009, I took a closer look at a disintegrating family scrapbook my Aunt Flo had kept. It contained yellowed news clippings from 1928 and 1930. In 1928, my father was being applauded for his 40 years of stellar service at City Hall. In 1930, he was being forced out by new Mayor Camillien Houde.

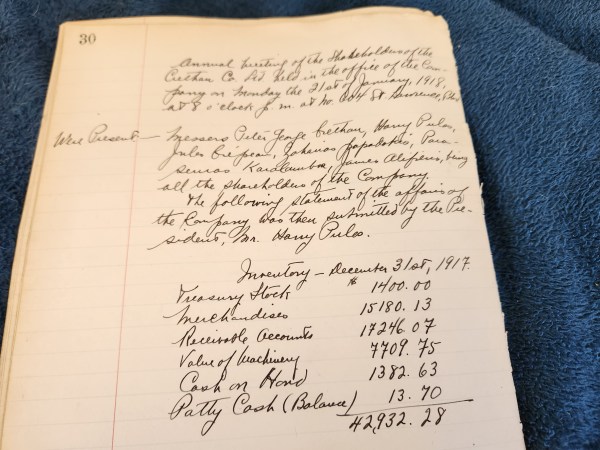

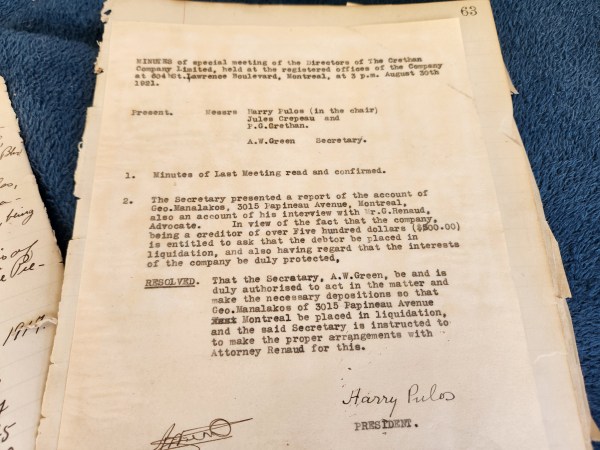

I noticed that the dilapidated black volume had originally been a minute book for The Crethan Company, a confectionery/food distribution company run out of Clarke Street by a handful of Greek men as well as my grandfather.

The President was Harry Pulos aka Harambolous Koutsogiannapoulos, the defacto leader of the early Greek Community in Montreal.2 How interesting.

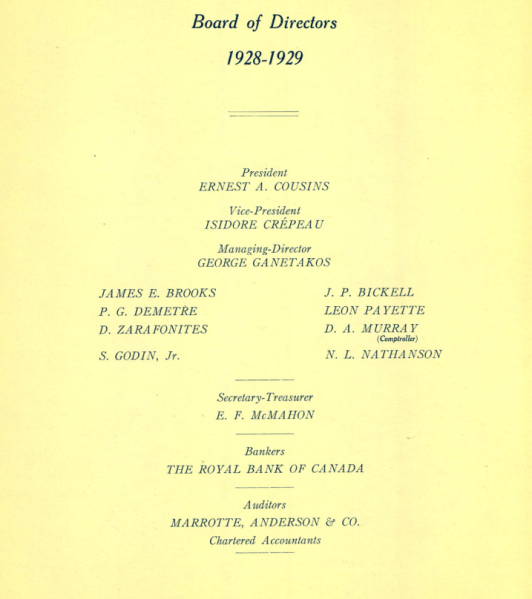

You see, by that time, I had researched my genealogy and discovered that my mom’s Uncle Isadore Crepeau had been VP of United Amusements, a movie distribution titan founded in the 1910’s by Laconian immigrant George Ganetakos. Ernest Cousins, an Anglo businessman was President..

So, I checked to see if these two men, Harry Pulos and George Ganetakos, were related: the answer is very likely.3

My mother had never mentioned her father’s Greek connections, not once, but she did talk about working in the Montreal movie biz before she was married.

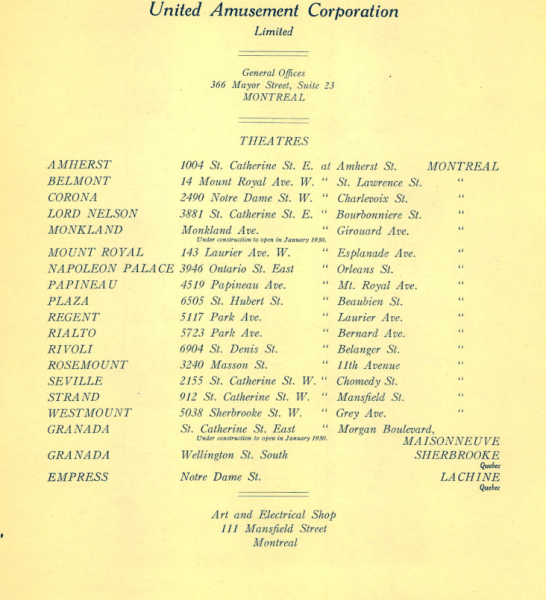

In 1941, right out of Marguerite Bourgeoys secretarial school, my mom got a job at RKO Movie Distribution, a United Amusements affiliate.4 Both companies were located on Monkland Avenue in Notre Dame de Grace, near her family home at the corner of Oxford and Monkland. (LINK to story I Remember Maman)

Taking an even closer look at the Minute/Scrap Book I suddenly noticed the significance of the dates. The Crethan Company was started in 1916 and ran until (at least) 1922 when the minutes end.

Grandpapa Jules seems to have aligned himself at just the right time with these ambitious men from Laconia. They probably helped him land his prize post and, in turn, he helped them with motion picture and restaurant licenses. 5I can’t prove it, but Jules almost certainly got his brother Isadore, an insurance salesman, his gig as VP of United Amusements.

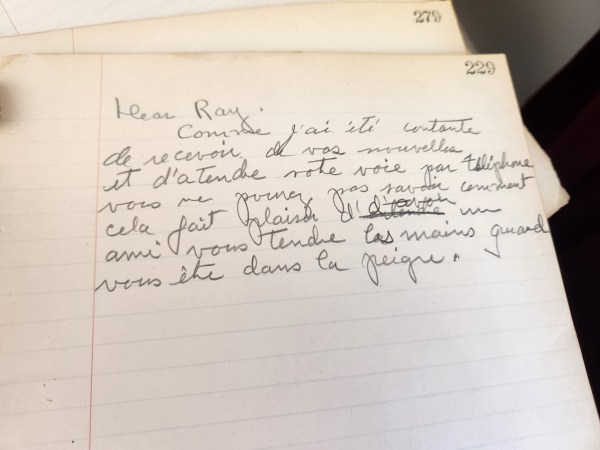

Dear Ray. How happy I was to receive your news and to hear your voice by telephone. .you can’t imagine how nice it is when a friend extends his hands when you are ‘dans la peigre.” Does she mean piege as in trap.Pegre as in underworld. If she meant Pegre, is she using a metaphor for ‘being grounded’ or does she truly mean ‘in the underworld?

In 1927 came the fatal Laurier Palace Motion Picture House Fire, where 78 children perished in a crush to the door. It was a real game changer in Quebec, and my grandfather got caught smack in the middle. He was blamed for looking the other way when citations were given to movie houses for letting in children unaccompanied by an adult.

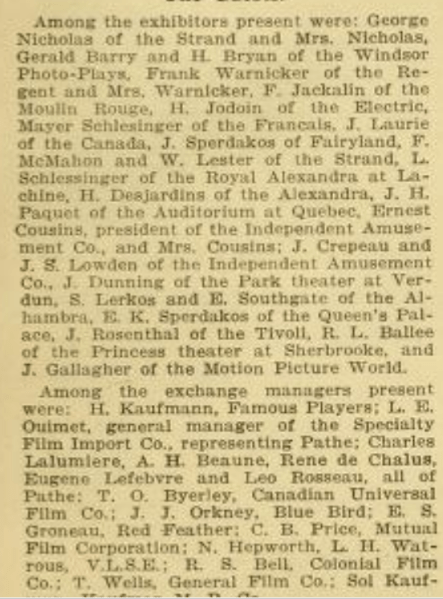

George Ganetakos, using the name George Nicolas, immediately set up a fund for the victims. During the inquest my grandfather brought in Earnest Cousins to plead for continued Sunday showings. Isadore also spoke. Sunday showings for adults were allowed to continue.

As it happens, two years before in late 1924 during an inquest into organized crime, corrupt policemen and Montreal’s sex industry, a cop-on-the-take took the stand and accused the Greeks of “corralling” children into movie houses and warned, “one day there’s going to be a fire and no one will be able to get out.” He wasn’t even being asked about movie houses: He brought this up out of the blue. I suspect this cop was a go-between and he was sending a coded message to my grandfather.

My grandfather certainly thought so. He had that same policeman fired the very next day.

My grandfather, in turn, was ousted in 1930 by the new Houde administration, but not before negotiating a huge life pension, likely in exchange for his silence. In 1937, during the Depression his hefty pension was rescinded by City Hall as an emergency measure – and just two weeks later my grandfather got run over by a plain clothes policeman near his home in NDG. Hmm. He spent 3 months in hospital and died the next year of complications at the age of 59.

My opinion only: Obviously my grandfather had nothing to do with the fatal fire, but his enemies may have had a hand in it.

The Laurier Palace was owned by Syrians, a group that was often conflated with Greeks back in those days.

Funny, whenever I’d ask my mom why I couldn’t go to the movies as a child she would tell me the story of ‘all the little babies who died in the Laurier Palace Fire’ and she’d pretend to rock an infant in her arms.

She didn’t know the real story.

The End

- L.O. David, the patrician head City Clerk, was a scholar who preferred working on his history books over the bureaucracy of City Hall. My eager-beaver grandfather got to do all the work! Montreal had universal male suffrage, but in the century earlier Montreal was an English majority city and the Mayors had to have 10,000 dollars in the bank just to run and the aldermen had to have 2,000 dollars and be fluent in speech and writing. They abolished these rules in and around 1910 as the city grew, absorbing the suburbs. The city became majority French. They also abolished the rule that an English Mayor must follow a French Mayor. Populist mayors, petit bourgeois, were now elected instead of the well-educated professionals of the Victorian Age. It must also be noted that the post of Mayor became less and less powerful, almost a figurehead in the 1920’s with the Executive Committee having all the sway. 1910 saw an immigration boom, so there were important votes to be had among these newcomers.

- To Build the Dream, Sophia Florakas Petsalis. 2000 explains that Koutsagiannopoulos was a pre-turn of the twentieth century arrival who had a fruit store across from where Eaton’s would be built, a highbrow location. Phillip’s Square was so ritzy, it was one of the few areas female students from Royal Victoria College up on Sherbrooke, were permitted to venture. According to the book, Pulos made sure to take care of his fellow Laconians, finding them jobs upon landing, etc. Other names on the board: Pappas, Antoniou; Economides; Crethan, Pappadakis, Karalambos and at one point a Forget.

- Drouin (Greek EvangelizmosChurch Montreal) reveals that in 1907 a Zarafonity from Dourali Laconia married a Koutsgiannopoulos- a marriage witnessed by Ganetakos, also from Dourali. He likely had a Zarafonitis mother. Koutsogiannopoulos also was godfather to John Zarafonity son.

- Lovell’s Directory reveals this fact. She lived on Monkland and Oxford with her Mom and brother and sisters. Her dad died in 1938.

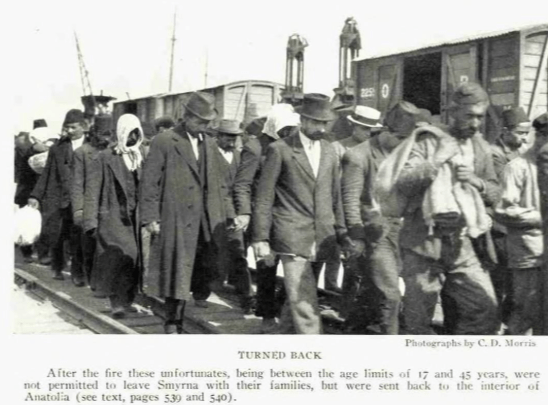

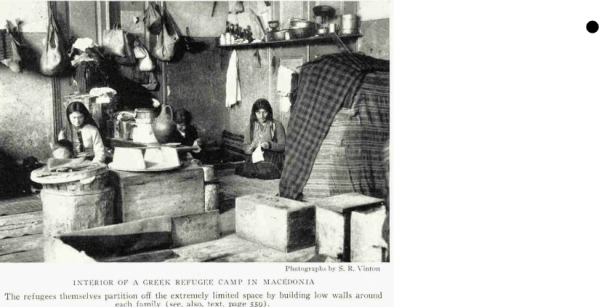

Greek men (mostly from Laconia, many related),were involved in all aspects of the movie distribution industry in Montreal back in the day. Ganetakos was only the most prominent of these movie men. The Syrians who were conflated with Greeks in the newspapers might have been Pontic Greeks from Turkey.

These new Canadians often started out working in the food industry, often pushing carts through the streets, then starting up stalls and then expanding into stores, cafes and restaurants.

The story goes that Ganetakos’s uncle, Demetre Zarafonitis, started playing ‘flickers’ at his fancy uptown café, the Cosy Parlour near Phillips Square, and that George noticed these early movies were more popular than the ice cream.So he started up his own motion picture house, the Moulin Rouge in 1908.

Two decades later, George Ganetakos was working out of his palatial office on Monkland Avenue, distributing Hollywood films for Famous Players and RKO, building architectural masterpieces like the Rialto Theatre on Park Avenue, and getting lots of press in the Hollywood trade journals. (My grandfather got a fair bit of press there as well.)

It seems that George Ganetakos was as much of a self-made man than my grandfather. However, I had contact with a descendant of the Zarafonitis’ and she was told her ancestors got the bum deal.

Greeks were referred to as Syrians in the press and they faced obstacles to their success by established merchants. People complained the cart pushers yelled too much on the street. At one point, the city wanted to tax stall merchants 200 a year as they did regular stores. An alderman, one loyal to my grandfather, spoke up for them saying this would force them out of business.

- During the Coderre Inquiry into Police Malfeasance in 1924, a policeman on the stand said that Jules personally forced policeman to look the other way when it came to underage clients of movie houses. He also said Greeks ‘corralled’ young children into the movie houses. He brought this up out of context. No one cared about children and movie houses. In those days, across North America, Sunday showings were often an all- kid affair. (The parents got an afternoon off). And besides, the streets at that time were dangerous with horses and autos running amok with no street rules. The Inquiry was about illegal booze and, mostly, the sex trade. In Juge Coderre’s final report in 1925, published in the Gazette and other places and rehashed for a 1926 US Senate hearing into Prohibition, the testimony getting into a two page spread in the New York Times, Coderre imperiously asked, “Who is this man Jules Crepeau who tells the Chief of Police what to do?”

A strange bit from a May 20,, 1916 Motion Picture World with the guestlist for a bash in honor of a Pathe movie star in town written by a Gazette reporter. Seems to show my Grandfather J. Crepeau with Ernest Cousins of “Independent Amusement”. Is this a typo, supposed to be I for Isadore? Either way a mystery. Did my grandfather dip his toe into the movie business as well as the food business in 1916? Or did Isadore have the movie gig as early as 1916? George Nicholas at top is likely George Ganetakos. (I have to delve deeper. I believe Indepent Amusement became United Amusements.) And is the T Wells my husband’s grandfather? See all the Greek names? Sperdakos, Lerakos etc. and M. Ouimet of the legendary Ouimetoscope.

Dec, 1921.