After my great grandfather retired from a successful 40-year career in the wholesale food business, he took an active interest in the stock market and managed his own investments during the time of the Great Stock Market Crash of 1929. Would he lose his life savings like so many unfortunate others at the time?

In a letter to his eldest daughter Josephine, my grandmother, dated June 2, 1932, he wrote:

“…if we could get rid of a lot of these Rotten Banks and Stock Market thieves the world would come around all right in no time. A person has no show with that New York Stock Exchange. Just a lot of crooks and I don’t think these common stocks have any value at all, not worth the paper they are written on, most of them, but all this will come (out) all right but people have got to lose a lot of money and that’s that.”

William Thomson Sherron (1863-1932) was born in Salem, New Jersey, the son of Albert Wood Sherron and Eveline Stokes Gaunt Githens. His wife, Gertrude Gill, (1869-1940), born in Philadelphia, was the daughter of Thomas Reeves Gill and Josephine Love.

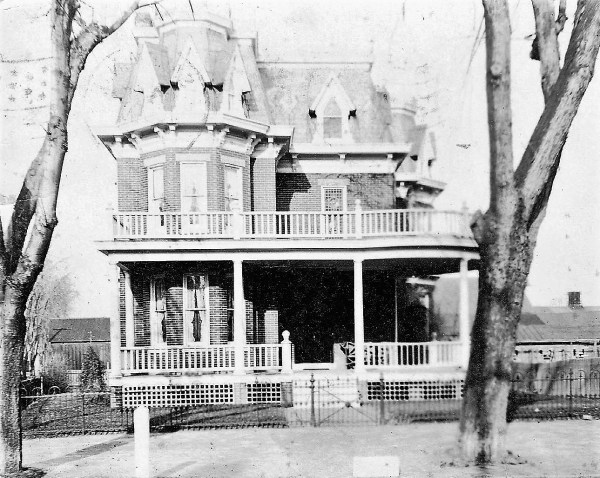

In November 1891, William and his bride settled in their new family home at 100 W. Broadway, Salem, New Jersey, where they stayed for the next twenty years. This beautifully refurbished Queen Anne style Victorian house still proudly stands today.

(Their first home -100 W. Broadway, Salem, New Jersey)

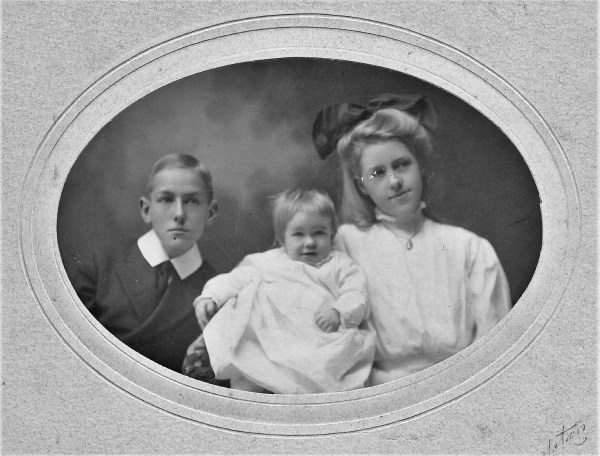

The couple had three children – Josephine (1893-1964) Social Media – Then and Now, Roger (1895-1963) Sherron and his Texas Betty and Alberta (1906-1992) Elopement … or not?. Josephine, my grandmother, her stockbroker husband and their two sons eventually settled in Montreal, Quebec. Their son Roger had mental health issues and lived with them until their deaths. Alberta married very young, had a son nine months later and remarried happily a while after that and had three more children.

(Roger, Alberta and Josephine Sherron – 1906)

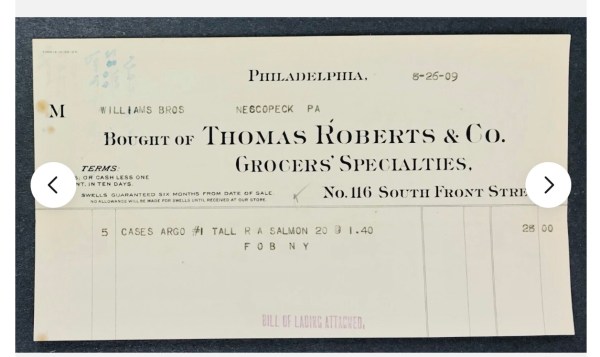

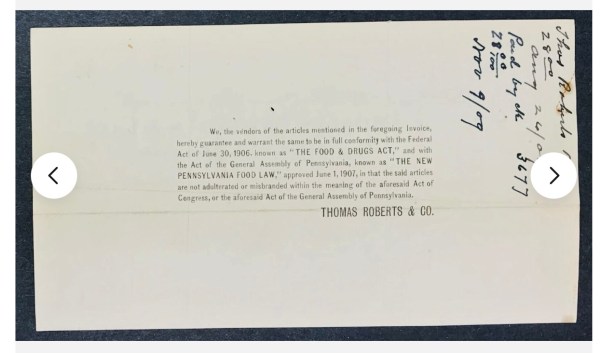

William first worked for Thomas Roberts & Co. in the wholesale grocery business for 25 years in Philadelphia before going into the same business for himself in 1905 at the age of 42. He opened his own office at no. 37 South Front Street, Philadelphia, about a half mile from their new home at 261 W. Harvey where they lived for the another twenty years.

(Invoice – front and back from the grocery wholesale business)

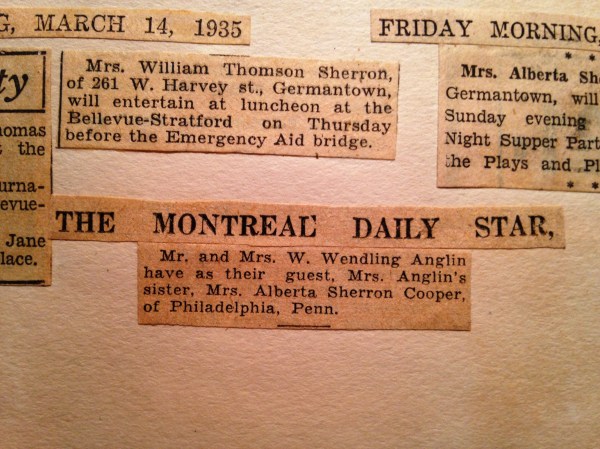

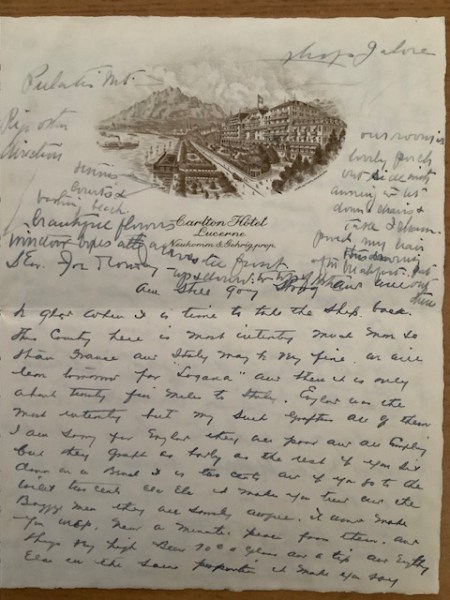

His wife and daughters took an active role the local Germantown social scene. Their endless teas, luncheons, bridge parties and charity fundraisers were regularly featured in the social pages of the local newspaper.

(Gertrude Sherron and her daughters in the Society Pages)

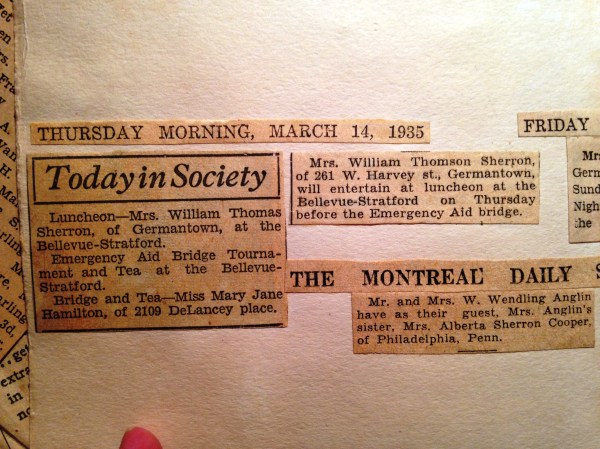

Along with the usual collection of family posed photographs in my dusty old boxes, I found a delightful photo of 55-year old William. He is holding up a string of sizable fish, possibly bass, outside “the Windsor Avenue cottage” (which looks more like an old country inn). He is wearing a light coloured baggy jacket and matching pants with a proper shirt and tie, white shoes and a floppy “fishing” hat. The smile on his face reflects pure joy for the day’s “catch”.

(William and his catch of the day!)

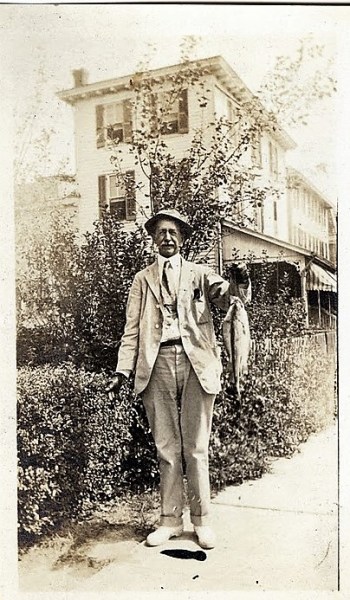

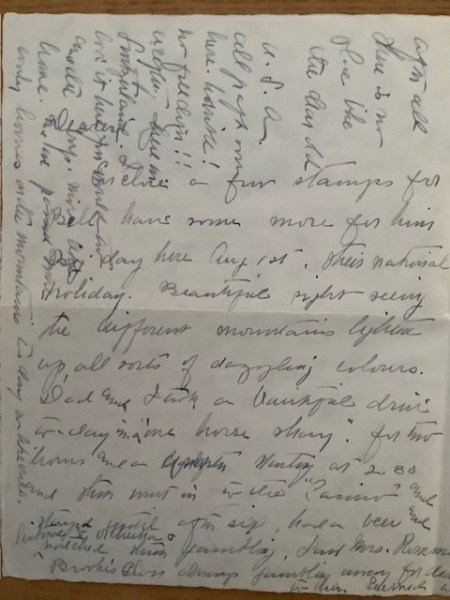

In 1930, just a couple of years before William’s death, the couple enjoyed an extended trip to Europe. They stayed at the famous luxurious Carlton Hotel in Lucerne while visiting Switzerland and I have the note sent to their daughter Josephine. William began the correspondence writing at a slant that became a little more difficult to maintain as he ran out of room on the notepaper. Then Gertrude took over filling every remaining inch of the note – to the bottom, up the sides and finishing up at the top of the page! Nevertheless, I could just barely make out from their undecipherable scrawls that they “adored Switzerland”, the hotel was “a dream” and “Interlaken was perfect”. As for Paris, Gertrude didn’t mince words when she exclaimed “Paris is a horribly dirty city.” However, she “loved London” and thought the people dressed “heaps better than in Paris.” At one point in the note, William generously invited their daughter to join them and wrote “I will pay the fare.”

(Excerpt of their note to their daughter Josephine)

So, it seems that William didn’t lose his money in the stock market after all, and had plenty to splurge on a once-in-a-lifetime trip to Europe with his wife.