Mourning Woman, 1883 Vincent Van Gogh

I had a great-granduncle who went by the name of William Richard Case Palmer O’Bray. William Richard was a brother to my great-grandfather. William Richard and his wife Margaret Elizabeth Burnett had a family of 14 children eight girls and six boys.

Three of his girls died within a month of each other and William Richard died at quite a young age, 44.

A shipwright by trade he lived, worked and died in New Brompton and Gillingham Kent, England. It would appear he had a hard life at work and at home.

William Richard’s occupation, in St. Mary, Pembrokeshire, Wales in 1871 when he was sixteen years old, was as an apprentice blacksmith. In 1881 he was a shipwright in Gillingham, Kent. By 1891, he lived in New Brompton, now part of the Medway District still working as a shipwright.

Shipwrights were responsible for constructing the structure of a ship and most of the internal fittings. Shipbuilding was a tough job, ships were built in open-air shipyards throughout the year, even in winter. The tools used, such as drills and riveters were loud and dangerous. (1)

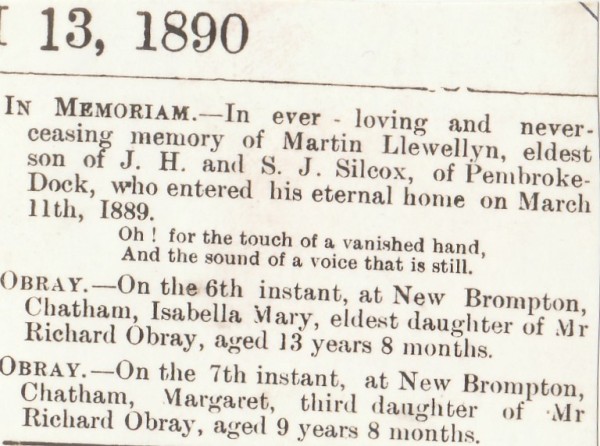

However, upon researching his family I discovered to my sadness that in 1890 on the 6th of March his eldest daughter, Isabella Mary aged 13, died. The very next day, Margaret Elizabeth, aged 9 years and 8 months died.

On the 13th of March 1890, the family posted an obituary for Isabella and Margaret.

Unfortunately, on the 23rd of March 1890, Minnie Ann (twin to Florence Ann), aged 3 years and 3 months also died. Below is the death card, typical for that era, for the three sisters. (3)

The text reads:

Three lights are from our household gone, three voices we loved are stilled; three places are vacant in our home, which never can be filled.

Not gone from memory, not gone from love, but gone to our Father’s home above”

I am in the process of obtaining the death certificates of the three girls, and I hope to add an update later on the cause of their deaths.

The 19th century in England was marked by the widespread prevalence of diseases such as tuberculosis, cholera, typhus fever and smallpox. These diseases posed significant medical challenges to society, with limited medical knowledge and resources available to combat them.(2)

My first thought was the profound shock my poor family must have suffered. William Richard Case Palmer suffered many tragedies in his short life.

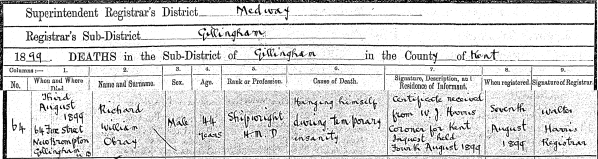

Ten years later, on the 3rd of August 1899, William Richard Case Palmer O’Bray died by his own hand. His death certificate reads:

“Hanging himself during temporary insanity”

Losing a child is not what a parent should experience, but to lose three in the same month is unimaginable. Was he depressed? I would think so, even 10 years later. There was nothing to help with the heartfelt losses in the 1800s. His wife, Margaret Elizabeth died in June 1919 aged 62 in Medway, Kent.

Sources:

(1) https://www.wcml.org.uk/our-collections/working-lives/shipwrights/

(2) 19thcentury.us/19th-century-diseases-in-england/

(3) This is my blog on British mourning cards.