Prologue: In my last post I explained how I recently learned, through DNA, that my biological father was likely Pontic Greek on the father’s side. Pontic Greeks are Orthodox Christian Turks who believed they are descended from ancient Greeks, who once lived on the southern coast of the Black Sea in cites like Samsun and Trabzon and who speak either a unique form of Greek or Turkish. In that post, I also wrote about the 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey. Here, I elaborate.

In 2010, I visited my older brother who lives in Denmark at his holiday home in Plomari, Lesbos, Greece. The large island of Lesbos is off the northwest coast of Turkey. On a good day you can see Turkey from the capital city of Mytilini. It’s only 17 miles away.

Back in 2010, before I explored my DNA, I naturally assumed I was half French Canadian and half Yorkshire British, just like my older brother, but I also knew, deep down in my heart of hearts, that I resembled the Greek locals, both in looks and in temperament.

The harbour is two streets down.

Today, I understand that I am very likely related to some of those local Greek citizens on Lesbos, perhaps even closely related. I know this because of a photograph I recently discovered in an article from the November, 1925 National Geographic magazine.

There is no shortage of online information on the 1923 Greek/Turk ‘population exchange’ that came on the heels of a horrific event referred to back then as ‘The Smyrna Holocaust,’ but I had high hopes that this story entitled History’s Greatest Trek. Tragedy stalks through the near east as Greece and Turkey exchange 2,000,000 of their people, written in real time by a world class journalist in a world class magazine, would shed some light on the path my Pontic bio-father (or grandfather) may have taken to reach Montreal, Canada in 1954.

I have tree matches in Samsun, a port on the Black Sea in northern Turkey. My mother, who lived and worked in the Notre Dame de Grace area of the city, likely knew Greek men whose grandparents fled Smyrna (now Izmir) in 1922, on the west coast of Anatolia on the Mediterranean Sea. Could I connect the two places?

I was not disappointed. Right at the beginning of the sixty page article there’s a picture of a young Greek man from Samsun. The caption reads: A Refugee from Samsun. He took part in the first trek of 100,000 refugees from the Anatolian interior.

According to online sources, post WWI, most elite Greeks in Samsun were killed off and all other able-bodied men sent into the interior to join the Turkish army.

Clearly, some of these Pontic Greek men and women escaped the Turkish hinterland to make it to the Mediterranean coast and Smyrna in 1922, in the hope of catching a ride to safety.

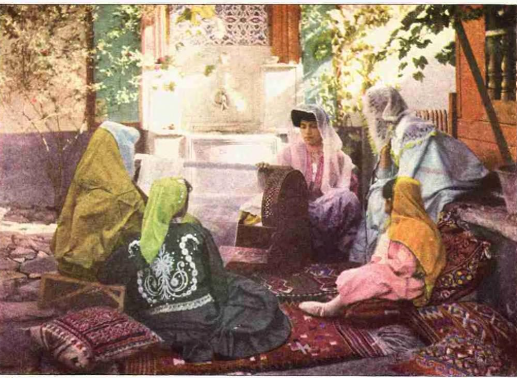

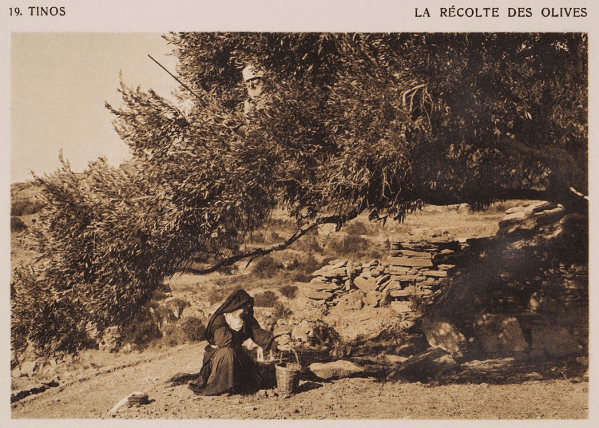

This 60 page article from 1925 is a classic piece of National Geographic reporting. It is workman-like in its execution with a prose style on the flowery side. The article offers readers a succinct historical and political perspective on the infamous 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey. The reporting is objective: The Muslim story is discussed with as much respect as the Christian story. And, of course, the article contains many, many photographs, about one hundred of them. Oddly, the prettiest colour ones all depict quiet Turkish life.

Still, the author, Melville Chater, pulls no punches as he uses his gift with words to capture the true horror of the situation in the port of Smyrna during the late summer of 1922: the hope, despair, death and disease and, eventually, the chaos, the total breakdown of civilized life.

Chater and his companion were in that coastal city when the Greek military lines collapsed in August, 1922, effectively ending the three year old Greco-Turkish war. They were in Smyrna in September to witness the Greek soldiers flee home on their military barques, leaving only ‘neutral’ observer boats in the habour.

Immediately thereafter, they saw the victorious Turkish cavalry enter the city, the riders’ left palms outstretched in a peace gesture, and a few days hence they witnessed the great fire of Smyrna that forced local citizens to flee in chaos to the quay and mix with the tens of thousands of refugees from further afield amassed there. By this time “the city had become a gigantic blast furnace… Affrighted faces mingled with wild-eyed animals, and human cries with the neigh of horses, the scream of camels, and, last, the squeaking of rats, as they scuttled by in droves from the underworld of a lost Smyrna.”

The beginning, late August, 1922.

“Refugees from anywhere within 150 miles inland herded seaward into Smyrna. At first they came in orderly trainloads or in carts, with rug-wrapped bedding, some little household equipment, and perhaps even a few animals, But as the distant military momentum speeded up, the influx became a wild rabble of ten, then twenty, then thirty thousand a day. Their increasingly scanty possessions betokened a mad and yet madder stampede from the scene of sword and fire, until September 7 saw utterly destitute multitudes staggering in, the women wailing over the first blows of family tragedy, whereby mothers with no food for their babies had been forced to abandon their older children in wayside villages….

….By now Smyrna’s broad quay swarmed with perhaps 150,000 exiles who camped and slept there, daily stretching their rugs as makeshift shelters against the sun, whose furnace-like heat was the mere forerunner to a terrible epic of fire.”

The Greek Army flees,the Turkish cavalry arrives.

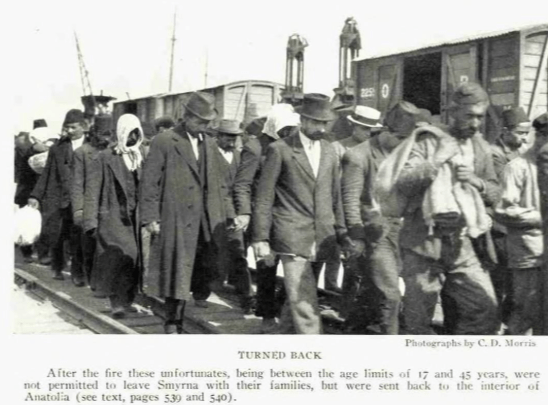

On September 23rd, a fire breaks out in the Armenian quarter. The Turks give permission for women and children and old men to leave. People are dispatched to Athens to organize a flotilla of rescue boats. The Turks then give the rescuers one week to evacuate the refugees or they will be forced into the interior. Further chaos ensues.

“Uncounted hundreds were crushed to death or pushed over the quayside to drown, on that first day, when eight ships, convoyed by American destroyers left with 43,000 souls aboard. For those left behind there remained but six more chances—a chance a day—then the black despair of deportation into the interior.

The aftermath:

A notification is posted permitting (well, forcing) all non-Muslims to leave Asia Minor before November, 30, 1922. Hoardes of Anatolian Greeks, former prisoners of war, men, women and children, head to the Black Sea coast.

“With ship-deserted quays, as at Smyrna, and with the Black Sea ports glutted with sidewalk-sleeping, disease breeding paupers, who had been thrifty cottagers a few weeks before, the gap was finally bridged by the arrival of Greek ships flying the Stars and Stripes and convoyed by American destroyers….

….”By January, 1923, Athens had slammed its official doors protesting against further expulsions.”

With a big nudge from the US, Britain and the League of Nations, Athens agreed to accept hundreds of thousands more Christian Greek refugees in an exchange for Muslims living in Greece.

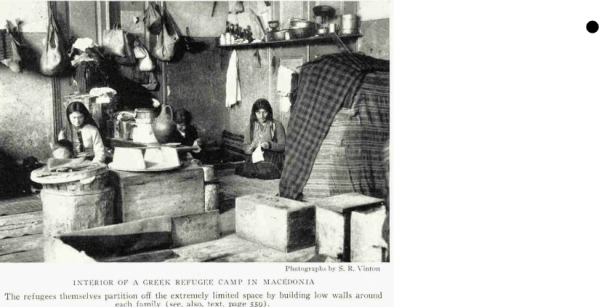

The exchange would begin in May, 1923 and be carried out in various ways. Most Greek refugees are funnelled to the Athens region as well as to Thessonaliki in the northern part of Greece and to some Aegean Islands like Lesbos.

They live in refugee camps rife with disease and death. There is little usable land left in Greece due to past wars.

Greece, then a country of 6 million souls, would take in almost a million and a quarter refugees within a year of the Smyrna disaster, increasing its population by 25 percent.

“There is no adequate parallel whereby to convey even remotely a picture of Greece’s plight in 1923,” Chater summarizes.

Pretty heavy stuff – and yet the 1925 magazine article somehow manages to maintain the feel of a breezy travelogue.

Epilogue:

In the style of Virginia Woolf’s 1925 masterpiece Mrs. Dalloway, I imagine a comfortably middle class lady, back in the mid 1920’s, perhaps my husband’s grandmother in her favourite club chair in her cottage in Westmount, flipping through this very issue of the National Geographic, cup of tea in one hand. The inky new pages crackle as she turns them with her free hand. “How awful,” she whispers under her breath when she gets to the bit about the Greek women holding their still-born babies at their breasts because they had no place to bury them. And, then, “How pretty,” as she eyes the flowing costumes on the Turkish women, the colourful mosques and the charming minurats. And, then, as she comes to the full-page advertisement for Campbell’s Soup at the end of the article, she perhaps thinks, “Yes, tomato soup for the children, for tomorrow’s lunch.”

Here’s the archive.org link.

https://archive.org/details/nationalgeographic19251101/page/550/mode/2up?q=mosques

![DSC06981[1]](https://genealogyensemble.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/dsc069811.jpg)