(Correction: I have been informed that is more likely that Reverend Henry Gordon took these photos, developed them and gave them to Miss Lindsay. The dog team photo would have been taken by Rev. Gordon during the winter and the fishermen in the boat must be south of Cartwright due to the lighthouse.)

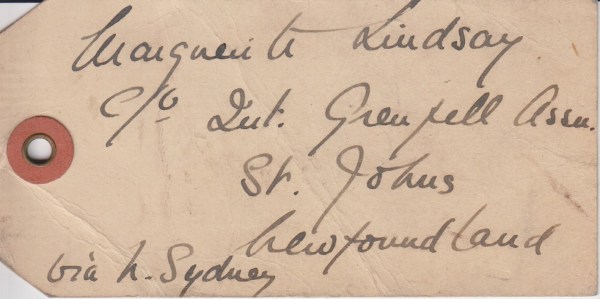

Miss Lindsay’s baggage tag- June 1922

Just over 100 years ago, my great-aunt volunteered as a summer teacher with the Grenfell Mission in Cartwright, Labrador, under Henry Gordon. In August 1922, just days before she was due to return home to Montreal, Quebec, she disappeared. Her body was found four months later, in December 1922, with a bullet through her heart.

I already wrote and published her story in seven parts (links below) and thought I had gleaned every bit of information possible from my “dusty old boxes.” But our ancestors want their story told and my great-aunt, Marguerite Lindsay (1896-1922), had quite a blockbuster to tell. Perhaps it was she who “tweaked” my cousin to finally look into his unopened boxes of family papers and memorabilia.

You can’t possibly imagine my excitement when I received his email:

“Hi Lucy,

Apologies for taking so long to get to this. I attach scans of the small

black-and-white prints of Labrador scenes that I found in the box of

clippings and photos. I assume that this is from when Stanley (sic) visited

the area after Marguerite’s death but don’t know for sure. Only two had

writing on the back – the dog team at rest and the school house. I

scanned those too in case you recognize the writing.

Lots of love!

Doug”

Eureka!

It appears that Miss Lindsay had access to a camera while she was there! And yes indeed I recognized her handwriting! It matched the writing on the tag on her baggage that accompanied her when she travelled to Labrador in June 1922. She went there to look after the youngest students (orphaned by the Spanish Flu epidemic) along with another volunteer, Anne Stiles from Boston, while their regular teacher took their summer break. Between the two of them, they oversaw all the children’s lessons, meals and activities.

A few days before she disappeared that August, she mailed a letter to her brother Stanley in Montreal. That precious last letter shared a long and loving detailed description of her life in Cartwright. The five newly discovered photos seem to match several parts in her last letter.

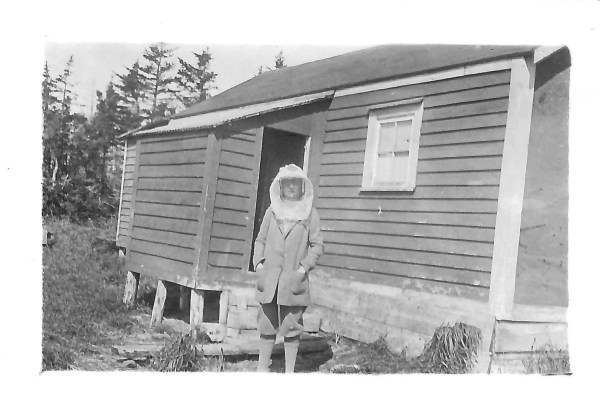

1. The first photo is of Marguerite wearing a hat she fabricated to protect her from all the bugs. The cabin in the background was a family home as she shared a room with Anne Stiles in the school dormitory that summer. This photo along with the commentary in her letter helps me imagine being there myself.

Miss Lindsay wearing her bug hat outside a family home beside the school in Muddy Bay

It is really cold here and foggy quite often, but very bracing, and I like it much better than heat; also when it is cold, there are no flies, and that means a great deal. I could compete with Sir Harry Johnson’s bugs in Africa, and match about even. The mosquitoes just swarm: at first you think it is fog or haze, lying low over the marshes, till you try and walk through them. We bathe in citronella. About 50 of them were getting free transportation on different portions of my anatomy, and I remarked to one of the natives, that the mosquitoes were bad; at which he laughed, and said to wait till they hid the sun, then I would call them bad.

The children are terribly bitten, and wail all night when they are extra bad. Well, there is a species of black fly, and their team work with the mosquito is extraordinary. They don’t bother to pierce your epidermis for themselves, but follow exactly in the footsteps of the mosquitoes, and they hurt. I could hardly turn my head for a day, the back of my neck was so bitten. I may have mentioned that there are no such things as screens on our windows; but we put up some surgical dressings, and tacked the gauze up as a slight protection. As little extras there are deer flies, flying ants and sand flies.

2. The second photo represents not only the local day-to-day fishing activities but other adventures like the exciting one she described in her letter.

Local fishermen in boat with Iceberg, south of Cartwright (there were no lighthouses near Cartwright)

It would be a great help if we had ice; but none comes up the bay. Some of the men tried to capture a young iceberg, and tow it home from the outside coast—behind the motor boat, but the friction of the rope wore through the ice, so it never arrived. Last Wednesday, Mr. Gordon told us we had been working so hard, we had better take a day off, and go up the bay with one of the fishermen, on an expedition for wood. We started off in a motor boat, towing an empty scow: just Anne and I, four boys of about 12, and the fisherman.

It was a perfect warm sunny afternoon, and Anne and I were almost asleep on the sloping bow of the boat, when we came around the point into a heavy wind and all but rolled off. It blew up very strongly, and Anne and I and the boys got into the very bottom of the boat, under our rugs for warmth. I was wearing everything I possessed; about what I wear for skiing. The fisherman was having a very hard time with the scow. It looked once or twice as though water would come down on our heads, when our boat got between the waves and it rested on the crest.

It took us over three hours to reach our destination – the point at White Bear river. There we went up to the warm cottage of some very kind fisher-folk, just as it started to pour, and thunder and lightning. We had expected to sleep on the floor, so had brought rugs; but Anne and I were given a bunk in a room about the size of a dugout, which was really comfortable after we had skillfully removed a pane of glass with a knife, the window being purely for ornament. They provided us with a feather bed in the bunk and warm dry rugs and fed us with smoked salmon and caribou meat. It was loads of fun.

3. The third photo shows the eager faces of a few of her students by the water’s edge hoping for a swim with Miss Lindsay that afternoon.

Some of Miss Lindsay’s summer pupils waiting for a swim

We are teaching the children to swim; the water is not so cold as you might think. There are some perfect walks around; nowhere are the trees too thick to push through; so though we have got lost once or twice, it is never for long. It is rather fun climbing the mountains; your feet get drenched, in the marsh, but we are used to that now. You would be amused to see me giving the children drill, and getting them to breathe through their noses.

We are going across the bay to hold nutrition classes, and persuade them to order whole wheat flour, instead of white.

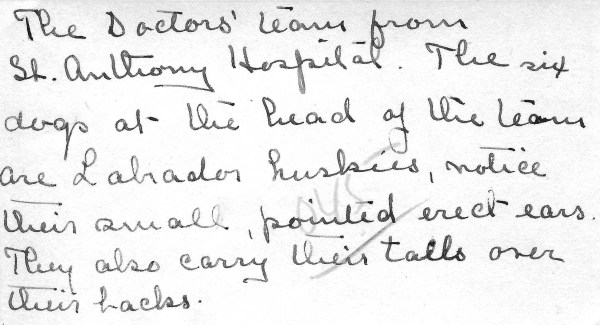

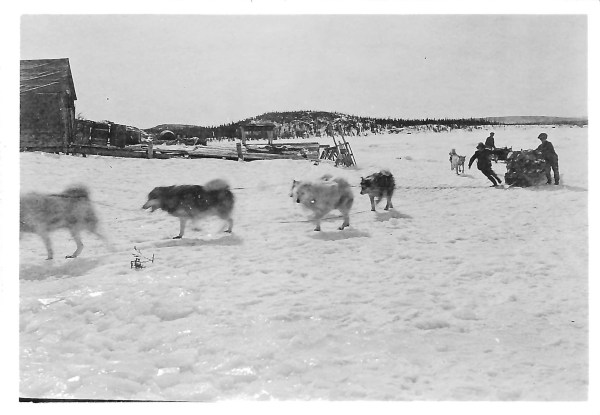

4. The fourth photo is of a dog and sled team. According to her note on the back, it belonged to the Doctor from St. Anthony (about 570km away). She noted that two Labrador Huskies lead the team and made special mention of their curled tails and pointed ears.

Local dog and sled team delivering wood in the winter time to the public school in Muddy Bay with a handwritten note on the back

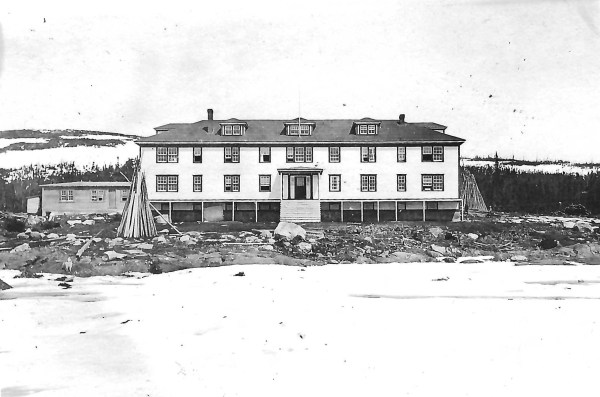

5. The fifth and final photo is of the newly constructed Labrador Public School in Muddy Bay, near Cartwright, which later burned down. The school in Cartwright today was named after her superior: The Henry Gordon Academy. To this day, the children are told Miss Lindsay’s story. Her handwritten note on the reverse side of this photo makes it that much more special for me.

Labrador Public School in Muddy Bay with handwritten note on the back.

I am so delighted about the recent discovery of these photos and very grateful to my cousin for finding these gems! I remain eagerly optimistic for more of Miss Lindsay’s undiscovered treasures to appear someday!

Miss Lindsay – The Early Years