The black-leather-lined plasticized bilingual identity card wacked my arm as it fell from the shelf. Until then, I had never really noticed the card among the many items my grandmother left me.

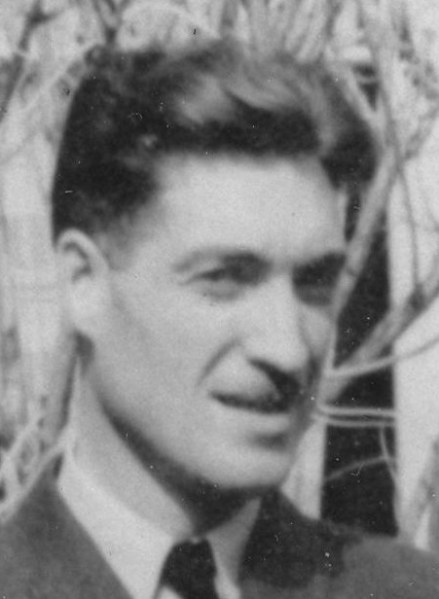

Luckily, its heavy construction protected the words on the card, which remain as legible as they were when my grandfather received it on January 4, 1936.

The Canadian federal “Department of Marine” issued the card to give my grandfather credibility as a radio inspector. It says:

“The bearer G. Arial is hereby authorized to issue and inspect private radio receiving licences in Edmonton East. He is further authorized to require the production of private radio receiving licences for inspection.”

Turns out that this little artifact hints at a short-lived controversy in Canadian history. The card expired on March 31, 1937, but it would be defunct before then.

The Department of Marine seems like an odd overseer of radio licences until you realize that early broadcasting began in the 1890s when Morse Code was used to enable ship-to-ship and ship-to-shore communication. The idea of a public broadcaster begin in May, 1907, when the Marconi station in Camperdown, Nova Scotia began broadcasting regular time signals to the public.

The “wireless telegraphy” industry continued to develop with private individuals investing in ham radios with no regulation. By June 1913, the federal government decided to regulate the industry to protect military communication.

When World War I began in August 1914, private licenses were banned altogether. Only the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company of Canada, Ltd. kept operating during the war years, in part because it became a research arm of the military.i

After the war, the private industry blossomed, particularly in Western Canada. Many of the new broadcasters came from multiple religious communities, a situation the federal government tried to prevent by setting up a public broadcasting system through the Radio Broadcasting Act of 1932.

That act led to the establishment of a licensing commission called the Canadian Radio Broadcasting Commission under the leadership of Hector Charlesworth. Charlesworth’s group censored many religious groups and political groups, but none more than the Jehovah’s Witnesses.

Norman James Fennema described the controversy in his 2003 dissertation, Remote Control.

…in Canada we find a situation in which the original impetus for regulating radio broadcasting began with the specific aim of putting a rein on religious broadcasting. Originally directed at the radio activities of the Watchtower Bible and Tract Society, this expanded in the early 1930’s into a policy against the licensing of religious broadcasters, a policy initially justified on the basis of the scarcity of the broadcasting spectrum, but that survived the expansion of the system.ii

By 1935, Clarence Decateur Howe became both the Minister of Railways and Canals and the Minister of Marine,iii the ministry under which my grandfather’s job was created.

Howe favoured private broadcasting, and encouraged new private entities to flourish.

Prime Minister Mackenzie King preferred a public broadcast system however. In February, 1936, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) came into being, and my grandfather’s job ended.

Sources

i https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_broadcasting_in_Canada, accessed May 26, 2020.

ii Fennema, Norman James. REMOTE CONTROL: A History of the Regulation of Religion in the Canadian Public Square, PhD thesis, 2003, https://dspace.library.uvic.ca/bitstream/handle/1828/10314/Fennema_Norman James_PhD_2003.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

iii https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minister_of_Transport_(Canada), accessed May 26, 2020.