My 2X great-grandfather, George Murray Boggie, born in 1826 in Old Deer, Aberdeen, Scotland,1 spent his whole life in the Royal Navy. This was a life of adventure, variety, and camaraderie, but also homesickness, hard work, long hours, and sometimes sickness.

George didn’t start out wanting to be a sailor. When he was 15, and perhaps earlier, he and his brother, James worked as apprentice writers in Peterhead, Aberdeenshire. They lodged with John Bradie, a newsroom keeper. 2 John probably worked at the same newsroom as George and James.

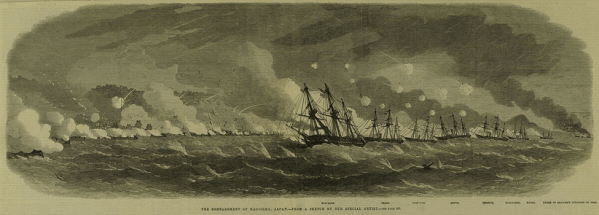

It turned out that writing was not the job for George. George started volunteering in the navy when he was 20. He served on about 14 ships between 1846 and 1854. In January 1854, he was serving on the HMS Euryalus. He then signed his indenture papers on 13 February 1854, which committed him to ten years of continuous service in the Royal Navy.3 The HMS Euryalus was commissioned in 1853 and soon after George joined the crew, it was deployed to the Baltic to take part in the Baltic Campaign as part of the Crimean War.4 The HMS Euryalus was part of an Anglo-French fleet that entered the Baltic to attak the Russian naval base of Kronstadt.5

While I do not have a picture of Great-Grandfather George, Royal Navy Form 95 says that he was 5 ft., 7.5 inches tall, with a ruddy complexion, dark hair, and blue eyes. He had a tattoo on his left arm, his initials: G.M.B. 7

George was already married and a father with two children when he started his indentureship. His daughter, Mary, was 4 and my great-grandfather, Henry was just two years old. His wife, Elspeth Milne would have had her hands full with a young family and an absent husband. Elspeth would also have been worried about George as he was in active military service. As George remained a member of the Royal Navy his entire working life, it is probable that he participated in many battles.

Sailors were constantly at work when at sea. All ships were dangerous workplaces and injuries and death as a result of injuries were common. Their sleeping quarters were cramped, the sailors’ sleep was often disturbed, and their meals were neither copious nor balanced. Although some ships did issue a daily ration of lime juice and sugar, but in quantities not exceeding one ounce of each, assumably to prevent scurvy. The ships were cold, damp, and uncomfortable and their clothes could be damp for months at a time. Most ships did not have a physician or surgeon on board so some health conditions could not be addressed quickly. Sailors’ wages were usually paid in arrears as a deterrent to desertion.8

Sailors were susceptible to tropical diseases and while dysentery can be caught anywhere, It’s a more common condition in tropical areas of the world with poor water sanitation. The Royal Navy sailed the world over, often in tropical waters. Dysentery on board was common. It is contagious and can be contracted from eating food prepared in unsanitary conditions or by drinking contaminated water. 9

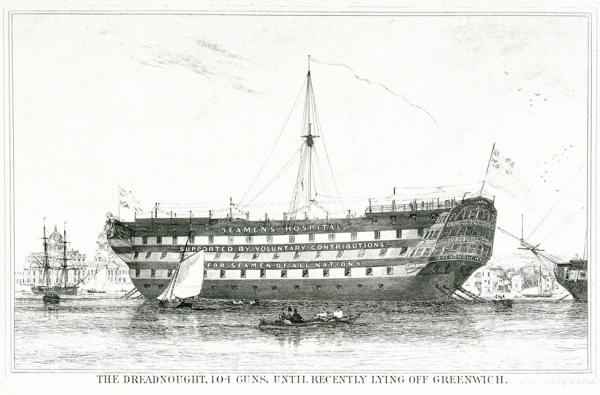

As George worked on 14 ships before he signed up for continuous service in 1854, he already had a good idea of what he was getting into. On 5 February 1847, George was admitted to the Dreadnought Seaman’s Hospital to treat dysentery.10 The registration indicates that he was victualled for 46 days which, I believe means that he was paid for the 46 days that he was in the hospital.

The Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital provided seafarers with hospital care for 150 years. It started in 1821 as a wooden warship moored in the River Thames at Greenwich, England. After 1870, the hospital transferred to dry land at the former Greenwich Hospital Infirmary, and the hospital continued to treat sailors in Greenwich until its closure in 1986.11 In 1987, a Dreadnought Unit opened at St. Thomas Hospital in London.12

George was a member of the Royal Navy during the second half of the 19th century and, at that time, naval warfare underwent a complete transformation due to steam propulsion and metal ship construction. While Britain was required to replace its entire naval fleet, it managed to do so through unparalleled shipbuilding capacity and financial resources.13 When George started his career, he served on a wooden hulled steam frigate. By the time he completed his career, he would have seen great leaps of technological improvements.

- Scotland’s People, Old Parish Registers, Boggie, George Murray, 1826, Old Deer, Aberdeenshire, accessed 7 June 2024.

- Scotland’s People, 1841 Census, Boggie, George Murray, Peterhead, Aberdeenshire, accessed 12 June 2024.

- Form 95, Indentured royal navy papers, Boggie, George Murray, dated 13 February 1854, National Archives, accessed 3 July 2024.

- Wikipedia, HMS Euryalus (1853), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Euryalus_(1853), accessed 20 November 2024.

- Wikipedia, Crimean War, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crimean_War#Baltic_theatre, accessed 20 November 2024.

- Wikipedia, HMS Euryalus (1853), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Euryalus_(1853), accessed 20 November 2024.

- Form 95, Indentured Royal Navy Papers, Boggie, George Murray, dated 13 February 1854, National Archives, accessed 3 July 2024.

- The Old Operating Theatre, Life at Sea: The Working Conditions and Health of a Sailor, https://oldoperatingtheatre.com/life-at-sea-the-working-conditions-and-health-of-a-sailor/, accessed 13 November 2024.

- Cleveland Clinic, Dysentery, https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/23567-dysentery, accessed 20 November 2024.

- Ancestry, Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital Admissions, 1826-1930, Boggie, George Murray, accessed 13 November 2024.

- Royal Museums Greenwich, https://www.rmg.co.uk/collections/hms-nhs-nautical-health-service-transcription-project, accessed 20 November 2024.

- Seafarer’s Hospital Society, https://seahospital.org.uk/about-us/our-history/, accessed 20 November 2024.

- Wikipedia, The Royal Navy, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Royal_Navy#:~:text=At%20the%20start%20of%20World,during%20the%20following%20four%20months