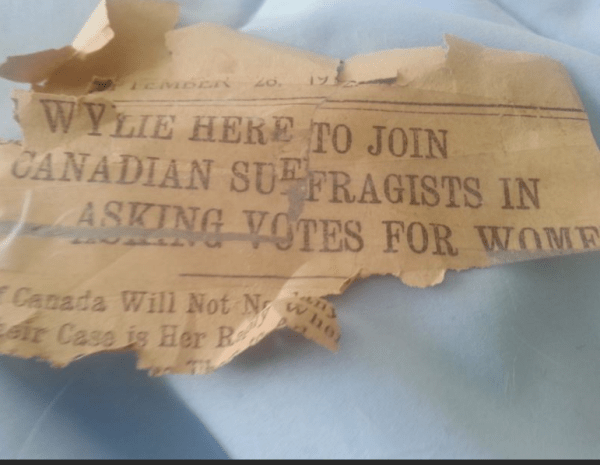

On September 26, 1912, a tall, slim, beautiful and well-dressed young woman stepped off the train at Viger Station in Montreal to be met, well, by no one.

There was a group of local reporters on the platform but they were waiting for someone else to arrive, someone far less fetching, as it were.

The journalists were expecting Barbara Wylie, a British suffragette. Wylie was one of Mrs. Pankhurst’s radical troops and British suffragettes were mostly manly, weren’t they?

When the reporters realized that this stylish beauty was, indeed, Miss Wylie it caused quite a commotion according to a newspaper article in the Montreal Witness clipped by my husband’s great aunt Edith Nicholson.

The reporters immediately raced over and encircled the lovely lady.

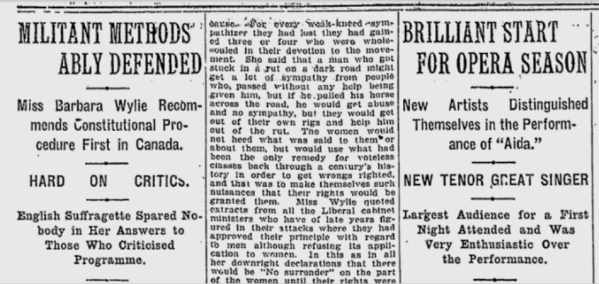

Barbara Wylie did not disappoint on the radical front. The Scottish firebrand brashly answered questions about her reason for coming to Canada and glibly defended a British suffragette who recently had thrown a hatchet at British Prime Minister Asquith. “Had it hit the mark, it might have knocked some sense into him.”

Whoa!

When I first found the Witness newspaper report among Edith’s massive stash of yellowed newspaper clippings on the suffrage movement, it did not make an impression on me. I had heard of the British suffragettes, for sure. Who hadn’t? But, the name of Barbara Wylie meant nothing.

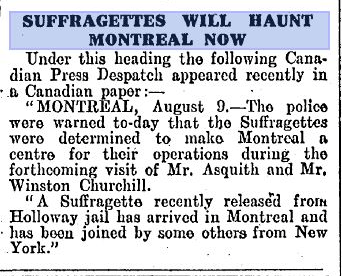

And I knew zilch about how, around 1910, some of Emmeline Pankhurst’s troops visited Montreal to try and convince “inert”1 Canadian suffragists that not-so-peaceful protest was actually the way to go.

Lets’ face it: there was nothing about Canadian women suffrage in my 1968 high school history book.

Miss Barbara Wylie was head of the Edinburgh Chapter of Mrs. Pankhurst’s Women’s Social and Political Union. She came to Canada in 1912 on a year-long country-wide tour, but her loose-cannon ways did not get her far.

In Montreal, on November 4, 1912, Wylie climbed the speaker’s platform at the YMCA as a guest of the Montreal Local Council of Women. News reports say she was wearing a pretty powder blue silk dress, but her rhetoric was of the red-hot variety.2 “Why speak of men as brave and women as pure? Would it not be better to bring the idea into society that men can be pure and women brave?”

The meeting had to be adjourned early when a fist fight nearly broke out – between two men.

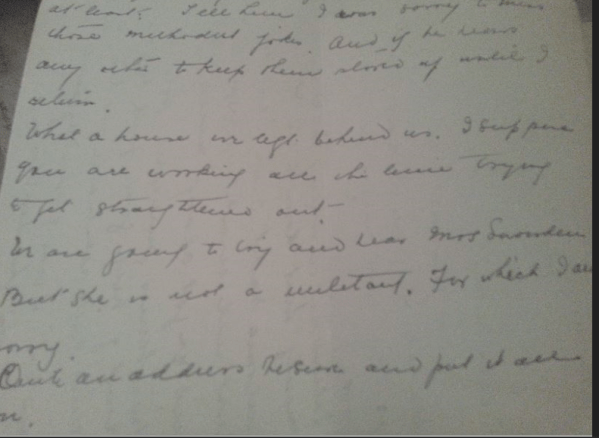

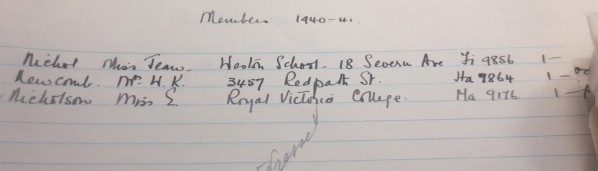

Edith Nicholson, 27, didn’t attend Wylie’s rowdy Montreal speech. A family letter reveals Edie returned home from Montreal to Richmond, Quebec on November 2. But the Montreal Witness clipping isn’t the only document I have that suggests Edie, an over-worked, under-paid teacher at Ecole Methodiste Westmount, was all for the “hysterical” window-smashing suffragettes.

On May 2, 1913, Edie is in Montreal with her two sisters, Marion and Flo, and she writes this in a letter home to her mom, Margaret: “We are going to hear Mrs. Snowden speak. But she is not a militant for which I am very sorry.”

This sentence, too, I might well have over-looked had it not been for that Wylie newsclipping because that fragile disintegrating memento prompted me to conduct more in-depth research on the messy, all-but-forgotten Montreal suffrage movement.

The first British suffragist brought in by the Montreal Council of Women was Mrs. Ethel Snowden, in 1909. Snowden was the young wife of a British Labour M.P. She spoke at Stevenson Hall.

Described in one report as “a daughter of the gods, divinely fair,” Snowden’s oratorical skills also impressed that day. She condemned the British militants, who were just beginning their ‘deeds, not words” path, saying “Mrs. Pankhurst has unleashed a Frankenstein monster.”

The Council soon passed an ambiguous resolution somewhat in favour of women suffrage.

Emmeline Pankhurst, herself, visited Montreal in December, 1911. She was brought in by Council President, Miss Carrie Derick (a closeted suffragette sympathizer) “so that women could hear the other side of the suffrage story.”

In her speech at Windsor Hall, the famed feminist, looking tired and frail, stated her case with eloquence but she made sure to avoid provocative language.

So afraid were Montrealers of Mrs. Pankhurst (whose troops back home were angry at Asquith over a broken promise) that the Council had to give away 200 tickets at the last minute and only broke even on the night. Mrs. Pankhurst’s fee was considerable too. After all, she was on the tour to raise money for lawyers.

May, 1913 saw Mrs. Snowden’s second visit to Montreal. This time she spoke at St. James Methodist Church.

In the spring of 1913, Mrs. Pankhurst’s militants in England were in full battle mode, setting fire to post boxes, hunger-striking in prison and playing ‘cat and mouse’ with the police.

Mrs. Snowden calmed the fears of Montrealers in the audience, telling them not to worry, women wouldn’t suddenly want to run for Parliament with the vote (sic). “All men care about is money, but women care about the home, children and humanity,” she proclaimed. The vote for women, it seems, was all about saving babies.

This is exactly what the majority of women in the Montreal suffrage movement wanted to hear. These ladies were mostly well-off middle-aged matrons or unmarried teachers of a certain age. They were maternal suffragists, not equal-rights suffragettes, and they had worked very hard to keep any young, excitable unmarried women (even of their own class) out of the local movement.

These matrons did not like what they saw coming out of the UK or the U.S: the spontaneous marches in sundry small towns; the highly-publicized cross-country tramps; the gigantic uber-organized parades in major cities, including one with10,000 people that swept down 5th Avenue in New York led by a young suffragette goddess on horseback. They were especially afraid for/of their own daughters: A lengthy editorial in the Montreal Gazette described women’s colleges like McGill’s Royal Victoria College as”suffragette factories” churning out de-sexed females.

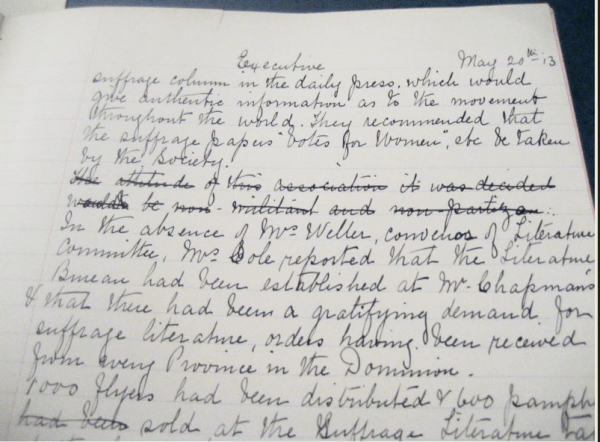

So, in March, 1913, they started up the Montreal Suffrage Association, an elite organization with a mandate to provide a ‘quiet and peaceful education of the people’ led reluctantly by, who else, Miss Carrie Derick – with a membership by invitation only.4

Ethel Snowden ended her 1913 speech by calling Mrs. Pankhurst’s troops “cavemen” giving the reporters their headline for the next day.

If Great Aunt Edie was in attendance that night in the large landmark Gothic Revival church on Ste. Catherine Street in Montreal, and I have no proof one way or another, she must have been mightily dismayed.

Originally published in Beads in A Necklace, Genealogy Ensemble’s compilation of family stories.

Furies Cross the Mersey is my story about the British Suffragette Invasion of 1912 from 3 different points of view. This era was a study in Media Literacy, that’s for sure. Journalists broke every rule of their trade covering the ladies of the suffrage movement. (For example: Were young suffragette sympathizers ‘manly and desexed’ or ‘excitable and hormonal?) Suffragists and Suffragettes wanted to take away men’s alcohol (overt)and their right to have sex before marriage with prostitutes (tacit). “Why can’t men be pure.” Mrs. Pankhurst, a doctor’s wife, was upset at the fact so many virginal women contracted veneral disease as a wedding present.(Hence the law requiring blood tests before marriage.). Also, many of her husband’s patients in the north of England arrived at his surgery pregnant by incest.

Margaret Votes published on this website. (How did Margaret Nicholson feel about voting for the first time in 1920? Very happy! Her neighbours not so much:) ) Most Canadian women won the right to vote in 1918. (Some with men in the military, earlier, in 1917) Quebec women in their province only in 1940.

- “Inert” was the word used by Carrie Derick to describe the Canadian Suffrage Movement in 1912.

- The British suffragettes, many of them young, were careful to dress well, knowing that it is easy to diss a woman on her appearance. This lead to news reports on the various marches in the UK and US sounding like fashion news.

- The Montreal Local Council of Women launched the MSA in 1913, despite the fact this was not their mandate. They were supposed to be an umbrella for the various women’s organizations that had sprung up from the grass roots. I believe they launched the MSA because some other British Suffragettes, namely Caroline Kenney, sister of Annie Kenney, Emmeline Pankhurst’s working class lieutenant, were trying to start up a militant group (open to all) and even planning a march to Ottawa in the style of Rosalie Jones’s tramp.

I know this because the Ottawa press covered their story, not the Montreal press. Another Kenney sister, Nell, had moved to Montreal (Verdun) with her journalist husband, Frank Randall Scott, in 1910, after he had swept her away to safety during a police action at a UK rally with Sir Winston Churchill, then the Home Secretary! His fonds are in the McCord Museum and include photographs of all the Kenney women – as well as the Royal Princes who came to visit in 1924. If you want to read more of their story read Furies Cross the Mersey, my book.

4. Carrie Derick is, famously, Canada’s first female university professor. A few other McGill professors were brought onto the Board of the Montreal Suffrage Association as well as some clergymen. The clergymen in particular hated – and feared – Mrs. Pankhurst. Many women on the Board secretly supported her, especially a Mrs. Weller, wife of a prosperous Westmount business man (electrical systems) who had made it a point to study the question in detail. She had invited Barbara Wylie into her home and she had visited the Suffragettes in England and had even given a speech about her visit.