In 1848, Montreal hardware merchant William Workman was encouraged to run for mayor. He refused. Twenty years later, Workman was elected as the city’s mayor, bringing his extensive experience in business, banking and philanthropy to the position for three years.

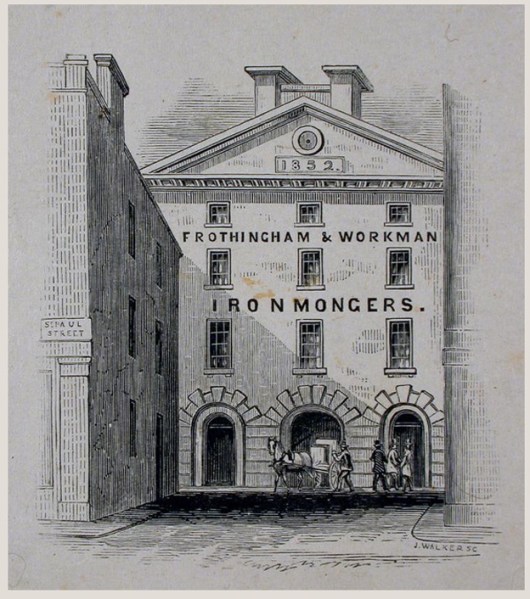

A Protestant immigrant from Ireland, Workman (1807-1878) came from a middle-class family. He became a partner with the Montreal wholesale hardware company Frothingham and Workman and, after retirement in 1859, he remained active on the boards of several banks and philanthropic organizations.1

In politics, he was a liberal and, like several of his eight siblings, a member of the Unitarian Church. “All the (Workman) brothers had been instilled with a strong sense of morality, had learned skills to earn their living, possessed an ability to think through issues for themselves, and seemed to seek knowledge for its own sake,” Christine Johnston wrote in her biography of Willam’s brother Dr. Joseph Workman.2

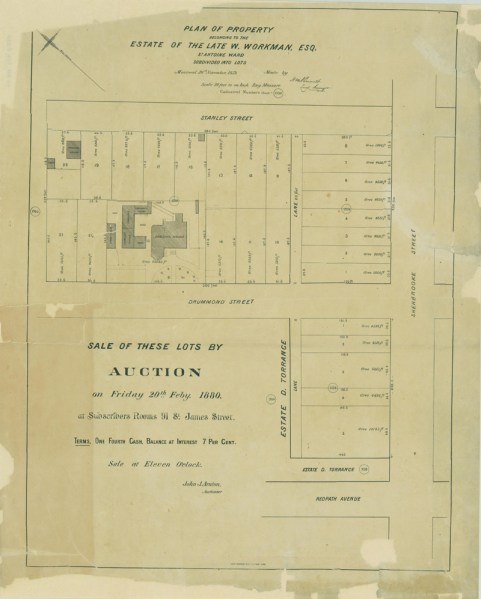

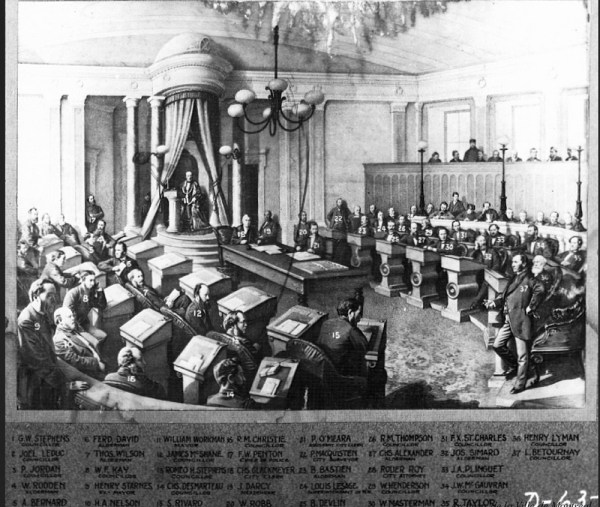

In 1868, when Workman agreed to run, democratic institutions were relatively new. Montreal had been incorporated as a city in 1833, but its mayor was not elected by public voters until 1852, and there was no secret ballot until 1889. At first, only property owners were eligible to vote. As of 1860, renters – and in this city, most people were renters – could vote, provided they had paid their taxes. Anyone running for mayor, however, had to own property worth at least 1000 pounds.3 Thus, most of the city’s early mayors were from the business community, and about 60 percent of the people elected to city council were anglophones.

Banker and railway entrepreneur William Molson put Workman’s name forward at a nomination meeting. His opponent was Jean-Louis-Beaudry, a businessman who had already served several years as mayor. At first, there was a question as to whether Workman was eligible to run, then Beaudry claimed that Workman should be disqualified. His objections were dismissed and Workman beat Beaudry with 3134 votes to 1862.4

In 1869 and 1870, Workman was acclaimed mayor, but he did not run again in 1871.

The most distressing of Montreal’s problems was the high mortality rate for young children. Some people suspected that this was linked to its water supply. Cholera epidemics had reached Montreal in 1832, 1849 and 1854, but even most physicians did not understand that cholera was caused by bacteria, spread in contaminated drinking water. Instead, they believed that disease was spread by miasma, or unpleasant vapours in the air. William Workman, however, may have had some understanding of the contagiousness of cholera because his brother Joseph had done his thesis on cholera while a medical student at McGill University.6

As president of the Montreal Sanitary Association, William realized the importance of clean water. Over the three years he served as mayor, he looked at municipal economic development and urban life as two sides of the same coin. He was the first mayor to do so.7 His administration focused on improving the city’s water system, improving sanitation and making the city more livable for residents.

Workman improved the city’s aqueduct system to ensure it could provide enough water to everyone. He ensured that the sewer system was modernized, replacing rotting wooden sewer pipes with clay ones. He also saw to it that low-lying areas, where potentially contaminated water could accumulate, were drained.7

He turned his attention to garbage collection, introducing regulations concerning the pickup of manure, dead animals, soot and ashes. People were required to store waste in boxes or barrels, and the city now picked up garbage on a daily basis. The city built public baths, since many homes did not have hot running water, and it constructed municipal slaughterhouses.

To ensure that the city benefit all residents, he advocated for the creation of large public parks, on the top of Mount Royal and on Île Sainte-Hélène, where people could breathe pure air.8 Not long after Workman left office, the city purchased the necessary land and hired famous landscape architect Frederick Olmstead to design Mount Royal Park. It was officially opened in 1876 and it is still today a much-loved feature of Montreal. Île Sainte-Hélène, in the St. Lawrence River, also remains a popular green space.

One of the most exciting events of Workman’s time as mayor may have been the clear, crisp October day in 1869 when 19-year-old Prince Arthur, Queen Victoria’s third son, arrived in Montreal as part of a Canadian tour. Workman greeted the prince in the old port and made a short welcoming speech, then he and his guest took part in a procession through the streets. People cheered as they passed by, and homes and commercial buildings were decked out with banners and flags. The following day a lacrosse tournament took place.

Workman proved to be a very popular mayor among both English- and French-speaking Montrealers, and when he left office, citizens showed their appreciation. A public banquet was organized in his honour, and people from all classes came to thank him for his hard work and the generous hospitality he had offered to visitors. The Gazette was effusive in its description of the banquet and the expensive thank-you gifts of a diamond ring and silver dishes that Workman received.

The speech Workman gave during this dinner revealed that he had had concerns about going into politics. Addressing the crowd, and especially members of municipal council, he said, “I entered upon the duties of my office under great inexperience.… I laboured under great misgivings and suspicions as to the conduct of affairs in your corporate administration. Then, as now, the press had been sounding the alarm as to combinations, jobs and rings. I watched with great attention and anxiety in every department to discover the truth of these assertions, but I watched in vain and, after three years experience, I can truly say that, if it is one of the great blessings of a city … and of the citizens to find the corporate action of its representatives in unison with right and honest discharge of duty, then Montreal enjoys that blessing to its fullest extent.”

This story is also posted on my personal family history blog, http://www.writinguptheancestors.ca.

See also:

Janice Hamilton, “William Workman: Public Successes, Personal Problems” Genealogy Ensemble, Jan. 7, 2026, https://genealogyensemble.com/2026/01/07/william-workman-public-successes-personal-problems/

Photo credits:

Mayor William Workman, Montreal, QC, 1870, photo by William Notman, McCord Stewart Museum, 432611, accessed March 3, 2026

Archives de Montreal, Bref historique des élues et élus de la Ville de Montréal, https://archivesdemontreal.com/2021/06/01/bref-historique-des-elues-et-elus-de-la-ville-de-montreal/, Galerie photo,1870, https://archivesdemontreal.com/documents/2021/06/1870_VM166-D00015-22-5-002.jpg, accessed March 4, 2026

Kanien’kehá:ka group with William Workman, Mayor of Montreal, Montreal, QC, 1869; 1869 10 09; photo by James Inglis, McCord Stewart Museum, M6308, accessed March 4, 2026

Sources:

1. G. Tulchinsky, “WORKMAN, WILLIAM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed February 22, 2026. https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/workman_william_10E.html.

2. Christine I. M. Johnston, The Father of Canadian Psychiatry: Joseph Workman, Victoria: The Ogden Press, 2000, p. 38.

3. Archives de Montreal. Montreal: Democracy in Montreal from 1830 to the present: Electoral system. http://www2.ville.montreal.qc.ca/archives/democratie/democratie_en/expo/institutions-municipales/systeme-electoral/index.shtm, accessed Feb. 22, 2026.

4. Claude-V. Marsolais, Luc Desrochers, Robert Comeau, Histoire des maires de Montréal, Montreal: VLB Éditeur, 1993, p. 309

5. Paul-Andre Linteau, translated by Peter McCambridge, The History of Montreal: the story of a Great North American City, Montreal: Baraka Books, 2013. p 87.

6. Johnston, The Father of Canadian Psychiatry: Joseph Workman, p. 22.

7. Marsolais et al, Histoire des maires de Montreal, p. 87.

8. Archives de Montreal. Montreal: Democracy in Montreal from 1830 to the present: Mayors of Montreal: William Workman. (1868-1871), http://www2.ville.montreal.qc.ca/archives/democratie/democratie_en/expo/maires/workman/index.shtm, accessed Feb. 21, 2026

9. “Dinner to Wm. Workman, Esq.” The Gazette, March 8, 1871, p. 2. Newspapers.com, accessed Feb. 23, 2026.