The North Yorkshire town

Where my ancestors toiled

In the nearby fields

And laboured

In the limestone quarry

Or – in one case – bent over smartly

As footman to the local Earl

Is now a pristine tourist destination

For posh Londoners

(Who like to hunt partridge, grouse and pheasant)

With high-end clothing shops

And luxury gift boutiques

Lining the old market square

Two wellness spas

And at least one pricey Micheline-recommended restaurant

Serving up the likes of Whitby crab

(with elderflower)

Or herb-fed squab

On a bed of

Black Pudding.

The oh-so pretty North Yorkshire town

Where my two-times great-grandmother

A tailor’s wife

Bore her ten children

And worked ‘til her death at 71

As a grocer

(So says the online documentation)

Now has food specialty shops as eye-pleasing as any in Paris or Montreal

With berrisome cupcakes and buttery French pastries

(Some gluten-free, some vegan)

Mild Wendsleydale cheese

(From the udders of contented cows)

Locally-sourced artisanal game meats

Hormone-free, naturally

And free-range hen’s eggs with big bright orange yolks

That light up my morning mixing bowl like little suns gone super-nova.

And, for the culturally curious

Packages of the traditional North Country oatcakes

(Dry like cardboard if you ask me.)

It cannot be denied

Nary a wild rose nor red poppy is out of place

In this picturesque

Sheepy place

3000 years old!

(Apparently)

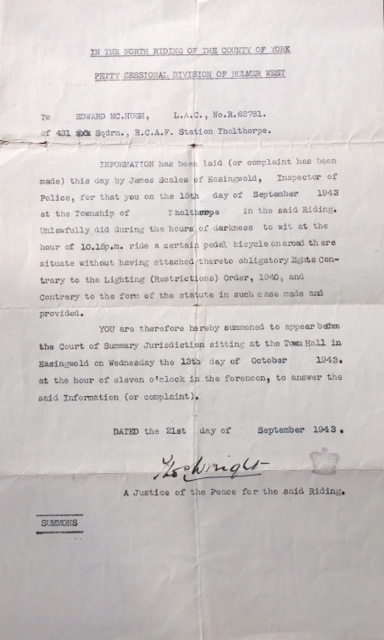

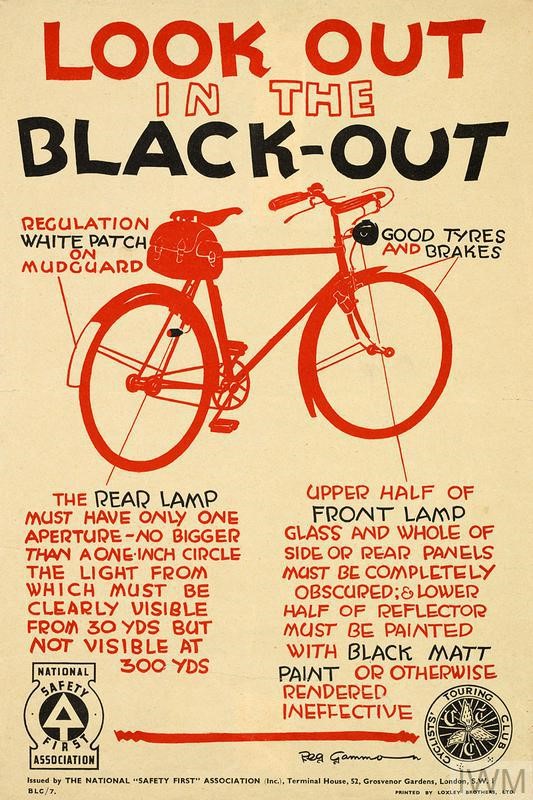

Where my great-grandfather

During WW1

Managed the Duncombe saw mill

Supplying timber for telephone poles

And trench walls.

Where because of the highly variable weather

(I’m assuming)

Rainbows regularly arched over the hills and dales

From Herriotville to Heathcliffetown,

Back then

As they

Do now.

(At least I met with one as I drove into my ancestral town– and thought it a good sign.)

Off-season,

This is a town for locals

Not for overseas imposters like us.

I was told…

The natives drive only short distances as a rule

From dirtier, busier places

like Northallerton

(but an hour away)

Through the awesome

(no hyperbole here)

Primeval forests and heathery plateaus

Of the much storied Moors

On narrow snaking highways.

Wearing rainproof quilted jackets in boring colours

They walk their well-behaved dogs

Spaniels mostly

In and out of ice cream shops

And cafes

Or up and down

the daunting (to me)

muddy

….medieval

…………..Fairy

…………………….Staircase

…………………………………..along

…………………………………………..the Cleveland

…………………………………………………………………….Way.

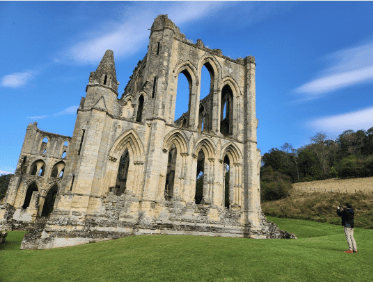

To visit quaint Rievaulx

And admire the Grade II Heritage cottages

With their bewitching thatched roofs

And wisteria-laced windows

Where the skeleton of the old Cisterian monastery

Rules the blue horizon

Like a giant antique crustacean trapped in grim History.

(Unlike myself, they do not pay the ten plus pounds to visit the Monastery ruins.

“And would you like to donate an extra 75p to the National Trust?”

Sure. Why not?)

They just like to walk their dogs.

Yes, all is picture-perfect these days

(It’s early October in 2024)

In my ancestral town

In the North of England

Where at least two in my family tree

Travelled the Evangelical Circuit

From Carlisle to Whitby

Preaching thrift and abstinence

And other old-fashioned values

To men and women with calloused hands

And a poor grasp of the alphabet.

Except, maybe, for the Old Methodist Cemetery

*no entrance fee required

Just around the corner from our charming air bnb

Where the crows, flocking for winter (I guess)

Caw maniacally in the moulting trees

And a black cat might cross your path

(It did for me)

And the old tombstones jut out helter-skelter like crooked mouldy teeth

From the soft-sinking Earth under which some of my ancestors lie,

Mostly

,,,,,,,But

Not ,,,,,,,,

,,,,,,,,,Entirely

Forgotten.,,,,,,,,,,