In 1665, 1,200 French soldiers arrived in New France to set up a series of fortresses along the Richelieu River to protect New France colonies in the Saint Lawrence Valley from the Five Nations of the Iroquois.

They were known as the Carignan-Salières Regiment and my ancestor Blaise Belleau dit LaRose was among them. He served in the La Tour Company, one of the 20 companies officially commanded by Marquis Henri de Chastelard de Salières. (Note: the regiment’s name came from a merger of the Salières Regiment with the regiment of Emmanuel Philibert of Savoy, Prince of Carignan, in 1660.)1

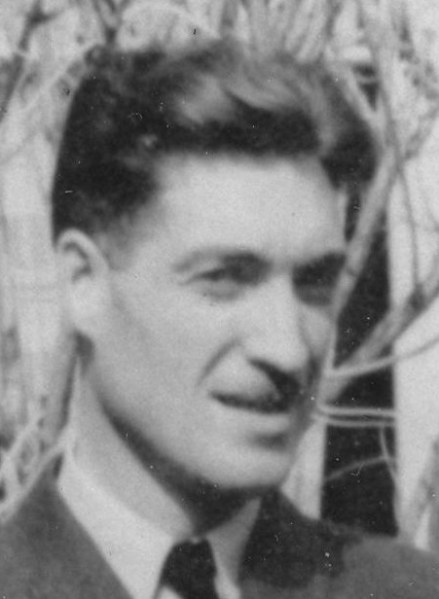

© Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec

Collection initiale

Cote : P600,S5,PAQ33

After Christmas 1664, Belleau left his parents (François Belleau and Marguerite Crevier) to join 1,099 soldiers in Marsal, Lorraine. They began marching across France in January 1665 to get to La Rochelle, where seven ships waited to carry them to New France. They were stationed on the Île d’Oléron and the Île de Ré prior to leaving.

On April 19, 1665, Belleau crossed the Atlantic Ocean on the Viex Siméon, a 200-ton ship piloted by Sieur Pierre Gaigneur. In addition to soldiers from the La Tour Company (probably eight officers and sub-officers: Captain, Lieutenant, Ensign, Sergeant, Corporal, Cadet, Drummer, and a Surgeon plus 50 soldiers), the ship carried passengers from the Chambly, Froment and Petit companies. They arrived in Quebec City on June 19.2

Another 200 men from four additional companies (Berthier, La Brisandière, La Durantaye and Monteil) arrived in Canada under the command of Alexandre de Prouville de Tracy, Lieutenant-General of the Antilles and New France on June 30. The rest of the soldiers continued arriving until the fall. (Note that some documents place my ancestor Belleau in the Berthier Company, which means he would have gone to the Antilles prior to getting to Quebec.)

The Regiment’s first task was to build forts Saint-Louis, Richelieu, and Sainte-Thérèse along the Richelieu River to block Iroquois intending to invade New France colonies. By late September, the forts were built and all the soldiers had arrived to fully station them. The Marquis de Tracy stationed others in Quebec City, Ville Marie (Montreal), and Trois-Rivières.

Although they initially served as defence forces, the following year, the regiment went on the offensive. By the winter of 1666, 500 to 600 soldiers, volunteers, and Indigenous allies headed towards Iroquois villages in what is now New York State. The cold and lack of food prevented them from continuing, however, and 60 men died en route. Despite that failure, some Iroquois Nations began negotiating peace treaties with New France. In September 1666, a second expedition of 1000 soldiers, 600 militiamen and 100 Hurons and Algonquins reached four abandoned Mohawk villages, which were burned to the ground. These attacks combined with smallpox and scarlet fever epidemics led the Mohawk Nation to sign a treaty with France in Quebec City on July 10, 1667. Eventually, all Five Iroquois Nations signed onto the treaty concluding the Beaver Wars and bringing a 17- to 18-year respite to New France.

The Carignan-Salières Regiment was recalled to France in 1668, but King Louis XIV offered land to soldiers and officers who wished to establish themselves in the new colonies. Belleau was among nearly 400 men who chose to demobilize and settle. He was also among another 283 men who married a Fille du Roi (King’s Daughter).

Blaise Belleau dit LaRose (also known as Bellot and Bezou) settled in the Sillery seigneury and built a home. He married Hélene Calais on September 25, 1673. By 1712, they had enough to donate a portion of land with a home to their son, Jean-Baptiste Bellot (Belleau), and his wife, Catherine Berthiaume.3

If you want to learn more about this period, the Fort Chambly National Historic Site demonstrates the military life during this era,

and will reopen for general admission in spring 2026. (Note that Fort Chambly was built in 1711. It is located at 2 Richelieu Street, Chambly, QC J3L 2B9. The website is https://parks.canada.ca/lhn-nhs/qc/fortchambly.)

Sources

1Arrivée du régiment de Carignan-Salières en Nouvelle-France, Répertoire du patrimoine culturel du Québec, which was an event designated by the Minister of Culture and Communications on June 19, 2015, https://www.patrimoine-culturel.gouv.qc.ca/detail.do?methode=consulter&id=26633&type=pge#

2Verney, Jack. The Good Regiment: the Carignan-Salières Regiment in Canada 1665-1668, McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1992.

38 mai 1712 [Document insinué le 30 août 1712], Cote : CR301,P755, Fonds Cour supérieure. District judiciaire de Québec. Insinuations – Archives nationales à Québec Id 81885, pièce provenant des registres des insinuations de la Prévôté de Québec, vol. 3 (Anciennement registres 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 et 12) (15 octobre 1709 – 24 mars 1715), pages 433-434, https://advitam.banq.qc.ca/notice/81885.