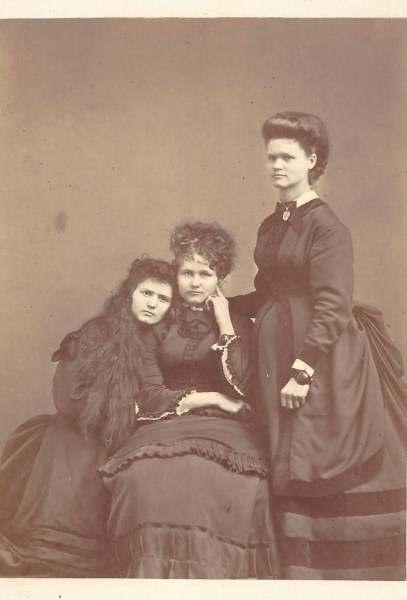

My mother, Mary-Marthe, would put herself out for people. At the check-out counter of the grocery store; on the bus; in the park my mother was not shy about helping out others. She sometimes forced spontaneous acts of kindness on complete strangers, often to my childish embarrassment.

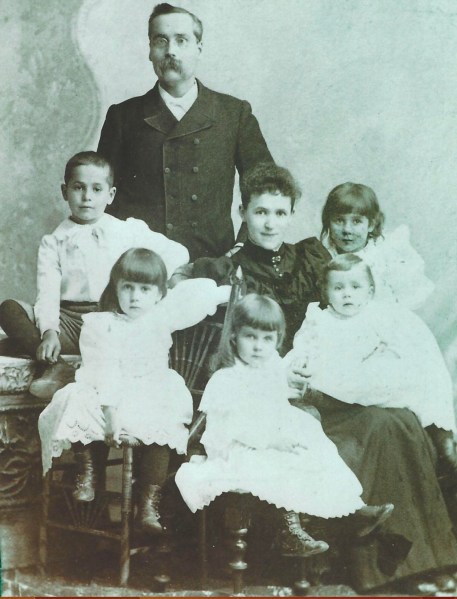

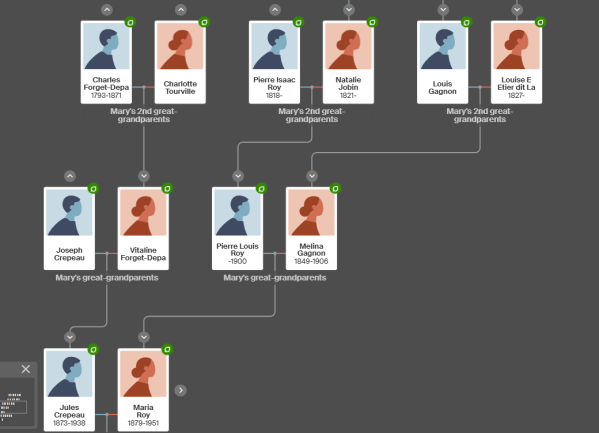

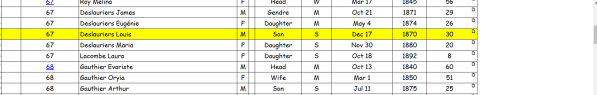

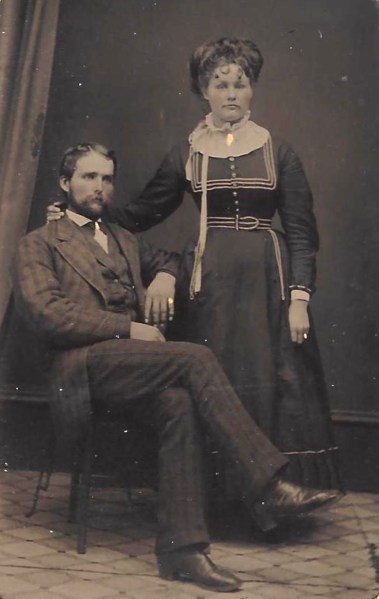

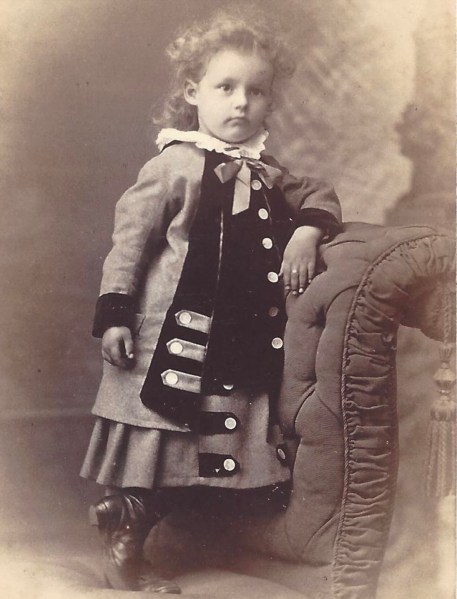

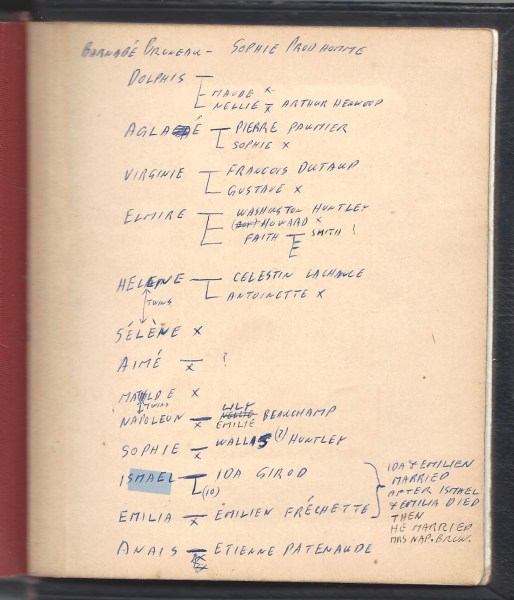

This habit, I imagine, she picked up from her own mother, Maria, a pious French Canadian who married well in 1901 and was generous with food and home-remedies.

The story goes that in the 1920’s my mother’s Sherbrooke Street West grey stone had a mark on the gate that indicated to homeless men, or ‘tramps’ as they called them, that a hearty meal was in store for them should they knock at the back door.

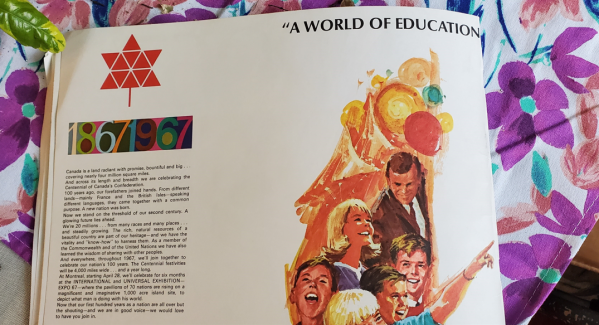

I most vividly recall an incident that unfolded in the summer of 1967, the year of Expo 67, the World’s Fair, when I was a young adolescent and because of my prickly age extra prone to being embarrassed by my mother.

My family lived in Montreal and we all had ‘ passports’ so we could visit the nearby World’s Fair anytime we wanted.

I was 12 years old and I sometimes took the number 65 bus to those blissfully bright Expo isles alone, likely skipping school, and the bus stop was right under my 6th grade classroom window! I wasn’t too afraid to be found out. Didn’t my teacher say we’d learn more at Expo than at school?

Over that six month period from May to October 1967 I travelled the short bus and metro route to Expo 50 times, sometimes alone, sometimes with my brothers or other relations and sometimes with friends and their families. I recall that one mom was so afraid of losing her many tweenage charges in the swelling sea of thrill seekers she looped a long rope around our waists to keep us contained. How embarrassing!

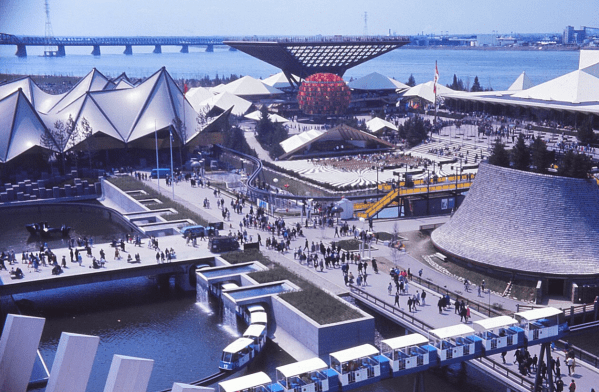

I wandered to the Expo site in all weather with a packed lunch since I had no extra money to spend.3 I liked the wide open Canadian and Ontario pavilions the best. I’d eat my sandwich on the Katimavik watching the rusty monster emerge from the lake adjacent. I experienced their exhilarating movies1 over and over again. The five Expo theme pavilions were a hit with me, too. 4I mostly avoided the popular national pavilions: the American, Russian, Czech and British pavilions with their long long line ups.

But I did like escaping to the sculpture garden behind the American pavilion. It was uncrowded, cool and peaceful in that place and all the avant-garde works of art, both life-like and abstract, were exciting to behold.2

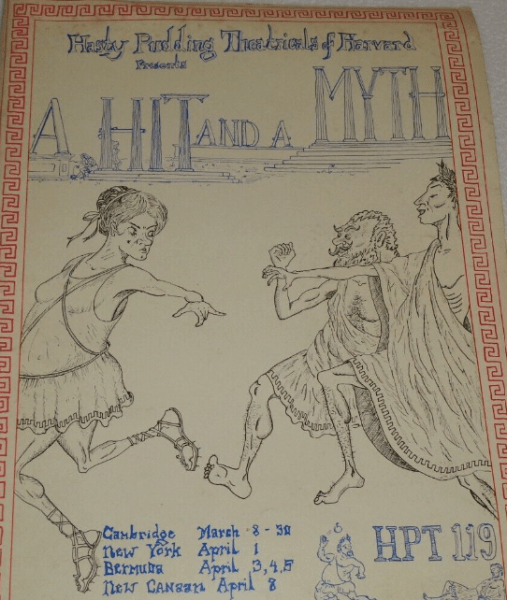

My older brother, a cutting-edge type, liked the Cuban pavilion for the vibes so we went there together, feeling slightly rebellious. He dragged me into the Christian pavilion one day and we saw a film with a monk setting himself on fire that depressed me for a days. And together we saw Harvard’s famous all-male Hasty Pudding troupe at an outdoor bandstand in a play called a Hit and a Myth that was quite bawdy. Although a good fit for my brother, it was bit mature (sic) for my tastes. I recall the energetic finale, Acalpulco, with a group of ‘grown men’ dressed like Carmen Miranda dancing in a conga line. Their unanchored brassieres kept riding up to their necks.

Yes, I went alone to those glittering Expo Isles in the St. Lawrence, despite the fact that in the spring a policeman had visited our sixth grade classroom to tell us about the dangers lurking there. He said a girl could be drugged in a bathroom and then sold into white slavery. I’m guessing I never mentioned this to my father and mother. I wasn’t too worried being used to walking the big city streets on my own and not understanding the term white slavery – something to do with snow, I imagined. However, I did keep a look out for any suspicious Boris Badenof types around the Russian Pavilion.

My father worked for Expo as a comptroller but I never visited the fair with him. He obviously was too busy. I did go with my mother, though, a few memorable times. On one occasion we saw Bobby Kennedy walk by surrounded by his team of FBI agents in dark glasses, and on another day we witnessed Haille Selassie, the Emperor of Ethiopia. He had a little dog following him. (I assume this wasn’t a coincidence. My mother wanted to see these famous figures.)

And on one very hot day my mom decided to visit the British pavilion. That place, more than any other, always had an especially long line up. This was the era of Swinging London, after all, and the pavilion included a MOD London exhibit with the Beatles (remember them?) and a Mini Minor Car. I was excited to go. I was a big fan of The Avengers with gorgeous Emma Peel karate-chopping Cold War baddies in her colourful Carnaby Street attire and of the Monkees TV show that featured Yardley commercials and “the London Look.”

My mom and I queued up realizing we probably had a very long time to wait. It was a hot day and in the line you couldn’t escape the sun. The person ahead of us was an ‘older’ woman with a young child – perhaps around 15 months old -who was not happy in the heat. The baby girl was kicking up a big fuss the whole time and would not be pacified, not in her stroller, not in her mother’s arms.

As was her way, my mother struck up a conversation with this woman.

She was British but this is where the similarity to Emma Peel or any other British ‘bird’ ended.

She was tall and thin, yes, but with wispy light brown hair and lots of stress lines around her eyes. Dowdy would be a good way to describe her attire. She was self-conscious about it, too. “I must look like the wreck of the Hesperus,” she said, combing back a rogue lock of hair with her hand.

This statement impressed me. Here was a smart British lady, just like my 6th grade teacher. And yes, in fact, this beleaguered mom was a teacher but in Toronto. She also had a 15 year old son who was off somewhere exploring the grounds – and she was divorced.

I started to feel sorry for her. She said she had driven to Montreal for just one day so her son could visit the Fair. Just one paltry day to see Expo, how sad! And all she wanted was to visit the pavilion of her homeland. Minutes, maybe hours ticked by and the long line inched forward. The little girl squirmed wildly in her mother’s arms, her shiny face getting redder and redder.

We were getting closer to the entrance and then my mother offered to do something very generous. She said WE would watch the baby for the woman in a shady area nearby so that she could visit the British pavilion in peace. (Our own visit would have to wait for another day.) And, what do you know, the woman took her up on the offer. I guess all that time in the line had made us seem safe and familiar to her.

The harried British mother passed through the turnstiles by herself and my mother and I and the baby found a big tree to sit under.

Then the lady returned and we said our goodbyes.

At Christmas she sent us a card with a long thank-you note written in impeccable teacher handwriting. (She had told us she didn’t have a phone. Too expensive.) I remember the note was on blue paper, maybe one of those aerograms popular in the day for overseas correspondence.

So, it seems, this overwhelmed mother did, indeed, appreciate my mother’s spontaneous act of kindness, as outrageous as it was – even for the 1960’s. I, myself, don’t recall being embarrassed at all.

2. https://expo67.ncf.ca/expo_sculpture_index.html

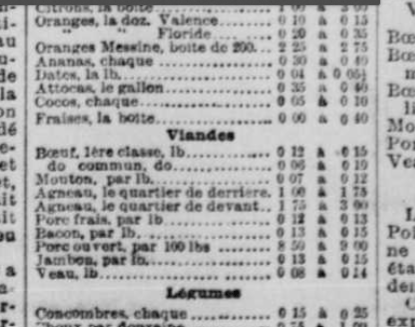

3. ” Take a bag of ham sandwiches and a thermos of coffee to Expo- where there are 146 restaurants and snack bars, 46 food shops and 500 automatic vending machines to serve you,” says the opening line of the article “Easting Exotically and otherwise at Expo,” in the Star Weekly insert for February 11, 1967. The pic shows Indian, Japanese, Italian and Mexican chefs with their exotic fare: tacos, pizza, sushi and a meal with pilau and nan. (I think I ate all these things this past weekend.) A pic on the next page caption says :A snack bar in Expo terminology means glamorous dining, indeed. (So, no real cheap food at Expo.) Oddly, the advert in this article was for KLIK and Kam luncheon meat with a pic of little squares of this ‘meat’ on toothpicks on a pickle. How ironic.

4. Man the Explorer; Man the Producer; Man the Creator; Man the Provider. I recall Man and the Community had a revolving exhibit (Czech artist) with little wooden models of a man and a woman in bed and all their needs revolving around them on a belt. “The cause of all progress is laziness.” Reading a list of that place’s exhibits, it sounds amazing. I want to go back!

The Star Weekly insert wrote about the Man out of Control? exhibit in Man the Producer with it’s “maze of signs showing man besieged by the information explosion.” The article continues: “The question mark in the title is no accident. Will the devices of man swallow him up or will he remain in control?” Hmm. Why do I feel this question to be extremely timely?