August 18, 1918

30 York Avenue, Westmount

My dearest sweetheart,

I cannot express in writing how pleased I was to hear your voice over the telephone a little while ago and was very sorry when I learned that due to the circumstances, you were not able to come home.

Dearest, I have never written you on this strain since I have known you and before I say what I have in mind, I beg of you to please try and understand it in the light that I mean it.

For Marion, dear, I love you with all my heart and it is because of my affection for you that I try to pave the way a little. I honestly, would not intentionally hurt you Marion.

Now sweetest, here it is: You know, Dear, that you have left me alone at different times for indefinite periods, but may I say that I have never yet found one month to be as long as this one.

Really, it has seemed to me almost like years. I would a thousand times rather be left entirely alone than to be left again with the girls, as I cannot get them to do anything which appears to me to be reasonable. I have come home on several occasions and the front and back doors were not locked. They will not close the windows and the house is almost like an oven. They forget to order food. The refrigerator is left open; the ice is melting as fast as you can put it in. Cawlice. Water is running all over the floor and things are lying about. I am sick and tired of the whole place.

Take pity on me Darling before I go crazy and come home to me to look after and love me. *but under no circumstances take chances (with mother’s health). Take it from me, God help the poor man that gets either one of them, if they don’t change. You can do more in five minutes than they can do together in a day. You have forgotten more than they’ll ever know. God bless you Marion and may it be God’s will that he can spare you to me for many long happy years.

Lovingly,

Hughie

PS. Don’t fail to burn this when finished reading.

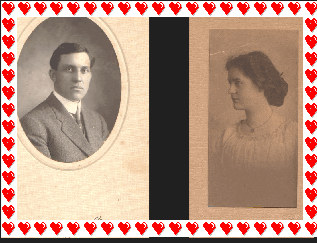

This rather amusing letter was sent under duress by my husband’s grandfather, Hugh Blair, to my husband’s grandmother, Marion Nicholson Blair in August 1918.

It seems Marion had taken her daughters, 12 month old Marion and three-year-old Margaret, from their home in Westmount, Quebec to visit her mother in Richmond, Quebec leaving her husband in the care of his sisters-in-law, Flora and Edith.

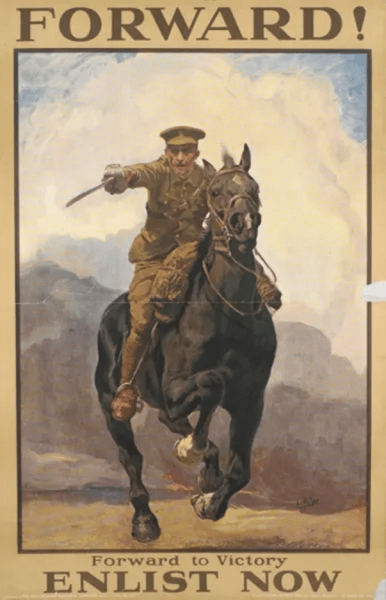

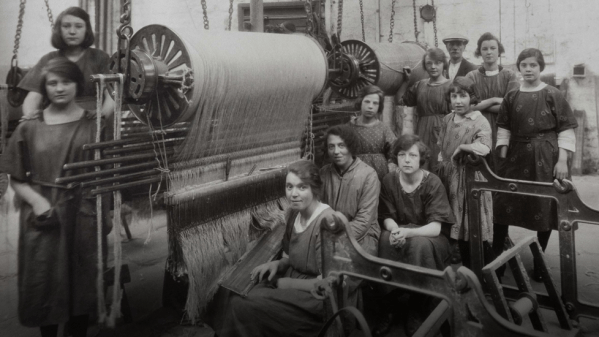

Hugh, clearly, is at his wit’s end. He is feeling neglected. Of course, his sisters-in-law have more important things to do. They have busy day jobs as teachers. WW1 is raging. Over and above their tiring day jobs, the women volunteer for the war effort. Many of their friends have lost brothers or sons at the Front. They can hardly feel sorry for Hugh.

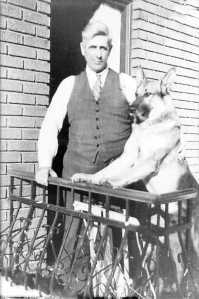

My husband’s grandfather, Hugh Christian Blair, born in Three Rivers Quebec in 1882, was a man of many faces. He could be a big baby, no question, but he was also a suave charmer, a savvy businessman, a talented carpenter and metalworker, a fine fiddler, a hockey player and curler and, ugh, judging from an album I have filled with photos of dead foxes and such, an ardent hunter.

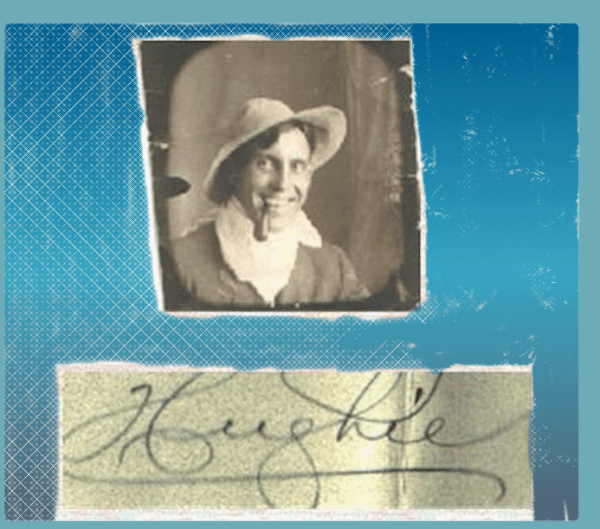

Hughie the joker with the stylish signature

He was the son of a prosperous Three River lumber baron and he worked in the family business.

In 1912-13, Hugh was courting his future wife, Marion Nicholson, daughter of Norman Nicholson, a very respectable but down-on-his-luck businessman from Richmond, Quebec.

Letters I have reveal that their one year courtship, from May 1912 to October 1913, has all the earmarks of a modern rom-com movie with its many ups and downs and breakups and make-ups and misunderstandings.

Let me summarize the plot for you:)

In May 1912, in his mid thirties and with good prospects, Hugh Christian Blair is introduced by his landlady to Marion Nicholson, a teacher at Royal Arthur School in Little Burgundy. Hugh is instantly smitten by this attractive firebrand, but first he must give his current girlfriend, Jean, a Momma’s girl, the brush-off. “Of course, you must know that we were never engaged and as for any understanding it must have been entirely on your part as I myself was only thinking of you as a very kind friend.” 1

He pursues Marion with all of his energy, taking her out of her stuffy rooming house to church as well as to more exciting places like the Orpheum Vaudeville Theatre and Dominion Thrill Park.

Marion is secretive about her life but sisters Flora and Edith keep their mother Margaret up to date about the budding romance, cheekily referring to Hugh in their letters as “Romeo” or “Hugh Dear.”

At the end of the school year Marion organizes a party at her rooming house. She strategically invites Hugh as well as another male friend. Neither of them shows up. She is furious. So the romance stalls. Marion returns to Richmond for the summer months.

In August, 1912, Flora and Marion visit a kind doctor cousin, Henry Watters, in Boston who takes them to Norumbega Park and a Bosox game. Henry isn’t the marrying kind, but another Boston relative, a Mrs. Coy, is keen on having Marion marry her son, Chester. Hugh somehow senses this. He writes Marion two long-winded letters while she is in Boston.

“I notice by the advertisements that there will be quite a few nice plays out this fall in Montreal. So if I am here – and of course you also – and care to take them in, I will enjoy taking you along. Of course, I would not like to neglect our Old Standby at the Orpheum. But I suppose there is no use planning too far ahead as many changes can take place between now and then.” It looks like he’s hedging his bets, doesn’t it?

It’s September. School begins anew. Marion is totally fed up with her rooming house with its suffocating curfews, so she finds a large flat to live in with her sister Flora and two other teachers in Mile End.

This is quite the revolutionary feminist act. Mr. Blair is a frequent visitor, so says Flora in her letters. (How scandalous!) However, Chester, “A great Yankee” also comes to visit.

Marion drawn by a fellow teacher

In November, Marion writes her Mom: “Hugh is helping with the double windows. Sometimes I like him, sometimes I hate him, but I wouldn’t know what to do without him.” Now, doesn’t that sound promising!

But something happens at Christmas (likely a dispute with the dad, Norman) that once again pours cold water on the romance.

In a telling January 3, 1913 letter to Marion, Hugh acknowledges receipt of her Christmas gift of cuff links and in turn says that the teddy bear he sent her was probably lost in the mail or stolen. Hmmm.

In February, 1913, Edith tells her Mom she went out with Hugh and Marion and he was all suave charm, “not the Hugh you had at Christmas.” Things are definitely looking up.

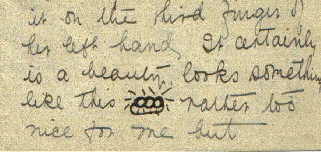

Sure enough in May 1913, Marion sends a letter to her mom with a drawing of her engagement ring.

A month later Hugh sends a very formal letter to Norman, her father, asking for Marion’s hand. Norman sends a letter to Marion saying “I can’t give my consent for I am dead broke.” 2. (Clearly giving consent is about money here.)

The men finally come to some arrangement but first Marion has to sign a miserly marriage contract that stipulates she gets nothing should the couple separate FOR ANY REASON. This is, likely, Hugh caving to his parents who do not approve of the marriage.

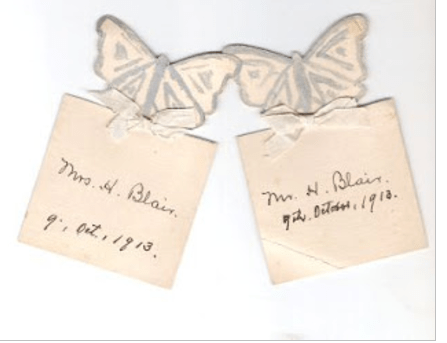

The couple weds in Richmond in October 1913. Hugh’s parents do not attend the wedding. Hugh leaves the family business to set off on his own.

Edith, Flora Hugh, Floss and Norman Nicholson, I suspect on the wedding day.

Wedding on the cheap.

But a Great War breaks out and Hugh soon reconciles with his parents and returns to the family business. (They need him: production is ramping up. Canadian lumber is key to the war effort apparently.) Hugh and Marion, with a newborn daughter, move from NDG to a cottage 4 on York avenue in Westmount near Hugh’s Aunt and Uncle.

Marion invites Flora to come live with them (with Hugh’s approval):

“It seems rather foolish to me to have you alone at Mrs. Ellis’s when there is room here. It is not that I need you especially for anything, but that I would like to have you with us.”

Marion tells how Hugh and his uncle work on their Victory Garden:

“Hugh and Willie are making a garden. What success they will have I do not know. One thing may be sure, the beds are straight and square. I would prefer to have more in them myself.”

Marion describes how much Hugh’s mother rails against Conscription:

“Everyone here, that is the Aunts and Grandma B are terribly worked up about conscription. All they say would fill a book and some of the sayings I do not find very deep. I would like to tell them that they are not the only ones who have sons who will be called, or they may think that theirs are more to them.”

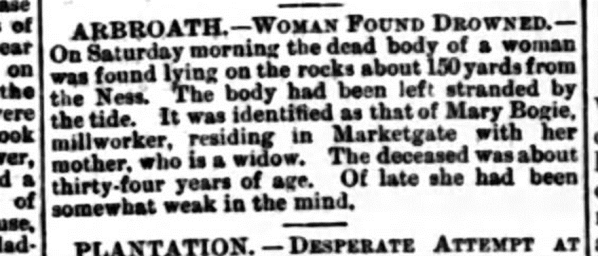

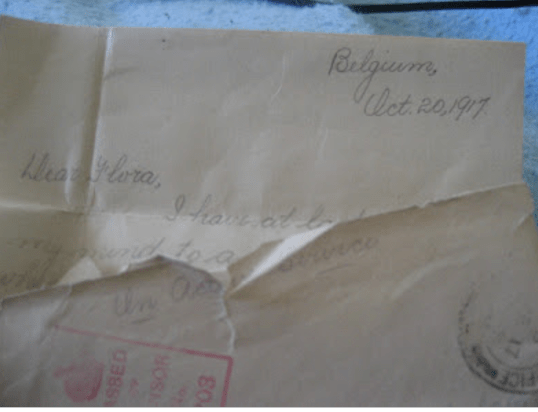

Letter from the Front. Flo’s friend, Ross Tucker. He survived, his brother Percy did not. Percey was killed just before Armistace. A sister died of the Spanish Flu. “That family is not the same,” says Edith in a letter.

And in July, 1918, just a couple of months before another scourge, the Spanish Flu, hits Quebec, Marion takes her two young daughters on a prolonged visit to her parents’ in Richmond and Hugh, left behind to swelter in the kitchen, has a meltdown. He writes her a long, plaintive letter he hopes his wife will burn after reading. Alas, she doesn’t burn the letter. BIG mistake!

Denouement.

Post war life is good for the Blairs. They have two more children, a girl and a boy, and spend a great deal of money, according to Edith. Marion’s father dies in 1921. Marion continues to regularly visit Richmond, a place her children come to cherish.

However, in 1926, Hugh contracts a liver disorder and passes away a year later – but not before signing away Marion’s rights to his portion of the family business on his deathbed – “as a temporary measure to facilitate business.” Marion Nicholson Blair is left with nothing to live on so she goes back to work as a teacher, wheeling and dealing to find sponsors for her children’s McGill education.

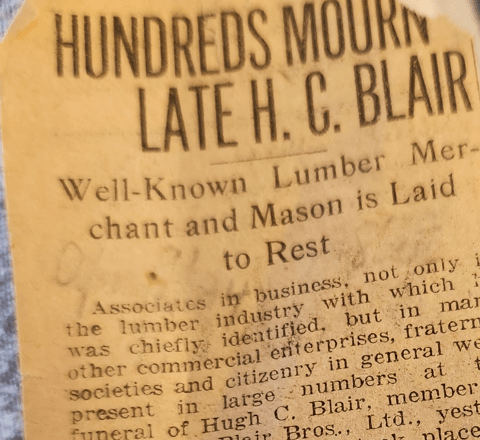

A last minute letter reveals that Hugh attempts to to purchase a burial plot in Melbourne Cemetery beside the Nicholson family plot. That doesn’t happen. Hugh Christian Blair is buried with his family on Mount Royal in Montreal. The funeral notice in the Gazette reveals it is packed with Masons but fails to mention Marion and her family as mourners.

Afterward:

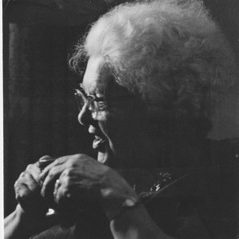

So, here we have the plot for a classic rom-com romance, but a movie with no happily-ever-after. Iron-willed Marion just rolls up her sleeves and goes back to work, despite great pressure put on her to remarry for the sake of her children. Indeed, she once told her children that being a lone parent wasn’t so bad: “At least I can make all the decisions for my family myself.”

Marion becomes a master-teacher and rises up to lead the Provincial Association of Protestant Teachers, or PAPT, during WW2 where she fights for teachers’ pensions.

In 1947, Marion dies of a heart attack before she can earn her pension.3 She receives a front page obituary in the Montreal Gazette, a major newspaper. “With the loss of Marion Blair the province, indeed, the whole Dominion has suffered a serious loss.”

In the 1960’s, the PAPT is one of the highest achieving public boards in North America and no doubt Marion Nicholson Blair had a role in making that happen.

1. This was the usual language used in such situations. I believe there must be a legal component to it. Indeed, the last line of the letter asks her ‘reply and tell me you have forgiven me.’

2. Many people believe this traditional gesture is romantic but it was practical, all about money. In Britain at least adults have been able to marry without consent for many centuries. However, without a dowry, most men couldn’t marry.

3. Marion’s heart condition first flares up in the year Hugh is dying. Edith suggests Hugh is very demanding and Marion, with four children, is run ragged meeting his needs. Edith also says Hugh’s eyes are yellow as yolk. A tube between the liver and stomach fell apart. It is a condition easily fixed nowadays.

4. 30 York Avenue is still there, a two story cottage. It’s on Google Maps.