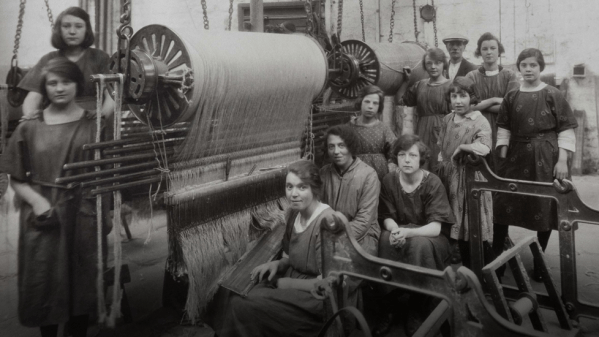

During World War I, 4,000 people, many of them women, assembled eight million fuses in a building locally known as “La Poudrière.” Given that the job required mounting a detonator cap over a gunpowder relay charge and attaching a safety pin (read more about WWI fuses here), the job was risky and monotonous at the same time.

Who were these people? How can we honour their work?

Recently, while looking through the records of World War I soldiers, I realized that their records may offer us ways to discover our homefront heroines. Several women moved to Verdun and lived within walking distance of the armament plant while their husbands or brothers served overseas.

Patrick Murray

When Ethel Henrietta Murray’s husband Patrick volunteered for the Canadian Over-Seas Expeditionary Force on Wednesday, April 12, 1916, the couple lived at 80 Anderson Street, in downtown Montreal.[1]

According to his military records, he died on October 29, 1917, driving with the 4th Brigade of the Canadian Field Artillery. She went by the first name Henrietta. Initially, she had moved to 1251 Wellington Street. Later, she lived at 956 Ethel Street.[2]

None of her addresses exist anymore, nor have I yet found any evidence explaining why she moved to Verdun. Based on her address and circumstances, however, I suspect that she—and three other women who lived nearby—worked at “la poudrière.”

La Poudrière

Locals call a building that currently houses 64 units for senior citizens “La Poudrière,” which means powder keg. The Canadien Slavowic Association (l’Association canadienne slave de Montréal) operates the space.

I haven’t yet looked into the records of the company to find out if there is a list of employees so that I can see if Ethel or Henrietta Murray appears on their rolls.

Other women I’d like to verify include Marjorie Victoria Stroude Luker, Ellen or Helen Elizabeth Winsper, and Mrs. John Sullivan. These three women also lived within walking distance of la poudrière between 1916 and 1919.

Military records include the addresses of these women because all of them received telegrams about loved ones being wounded or killed overseas.

Arthur Stroude

Marjorie’s husband Arthur was wounded in Italy on August 20, 1917, and then died of the flu in Belgium on December 2018. Although the couple lived in Point St. Charles when he signed up, her benefits were sent to her at 714 Ethel Street by the time he died.[3]

George Winsper

Ellen or Helen Elizabeth Winsper, the wife of George Winsper who died on November 7, 1917, had moved from Rosemont to 196 St. Charles Street in Pointe St. Charles by the time he died.[4]

William Wright

Two records mention the grief of Mrs. John Sullivan when Private William Wright, a steamfitter from Scotland, died in action at St. Julien on April 24, 1915. Neither have her first name. One document describes William, who was 21 when he died as the adopted child of Mr. and Mrs. John Sullivan. The one I think is correct mentions that she is his sister. Her address at the beginning of the war was 9 Farm Street, Point St. Charles, the same as his when he enlisted. His medals were sent to her at 431A Wellington St., Point St. Charles.[5]

If these women worked together, as is possible, they too risked their lives.

Employees with the British Munition Supply Company–which was created by The British Government under the auspices of The Imperial Munitions Board–faced the possibility of accidental explosions. Britain paid $175,000 in 1916 to construct a building that could contain shockwaves. It also included a saw-tooth roof to prevent sunlight from entering.[6]

British Munitions Limited

One description of their work comes from the biography of Sir Charles Gordon, who led the team that arranged for building construction.

One description of their work comes from the biography of Sir Charles Gordon, who led the team that arranged for building construction.

The IMB had inherited from Sir Samuel Hughes’s Shell Committee orders for artillery shells worth more than $282 million, contracts with over 400 different factories, and supervision of the manufacture of tens of millions of shells and ancillary parts. Its most serious problem was acquiring time and graze, or percussion, fuses for the shells produced by its factories. There was no capacity to create and assemble these precision parts in Canada, and contracts with American companies had proved dismal failures.

The problem was given to Gordon to solve. He recommended that fuse manufacturing be done in Canada. The IMB set up its own factory in Verdun (Montreal) to make the delicate time fuses. Skilled workmen and supervisors were quickly brought over from Britain to train Canadian workers. British Munitions Limited, the IMB’s first “national factory,” was open for business by the spring of 1916. The last order from Britain, for 3,000,000 fuses, came in 1917 and the last fuses were shipped in May 1918. British Munitions was then converted by the IMB into a shell-manufacturing facility.[7]

Another source I read said that Dominion Textile Company purchased the site for its textile operations when the war ended in 1919. Two decades later, Defence Industries Limited revived the site for a shell factory during World War II, between 1940 and 1945. David Fennario’s book “Motherhouse” offers a good look at the women’s lives during this second wartime era.

[1] Attestation Paper, Library and Archives Canada, RG 150, #347740, Patrick Murray, a derivative copy of the original signed by Patrick.

[2] Address card, ibid.

[3] Attestation Paper and address card, Library and Archives Canada, RG 150, #1054006, Arthur Luker.

[4] Attestation Paper and address card, Library and Archives Canada, RG 150, #920146, George Winsper.

[5] Library and Archives Canada, RG 150, #26024, William Wright.

[6] “Usine à munitions pour retraités slaves” by Raphaël Dallaire Ferland, ttps://www.ledevoir.com/societe/354100/usine-a-munitions-pour-retraites-slaves, accessed September 22, 2018.

[7] Biography – GORDON, SIR CHARLES BLAIR – Volume XVI (1931-1940) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gordon_charles_blair_16F.html, accessed September 22, 2018.