Recently, I was in the Montreal Courthouse accompanying a friend selected for Jury duty.

It was a four-hour wait so I had time to drink my coffee, look around and daydream. I watched as many lawyers dressed in black robes rushed in to buy coffee and dash out again. Others sat casually with clients over legal documents and I could tell they were lawyers only by their stiff white collars.

As I sat there, a distinct memory came back to me from my last courtroom visit to the Old Bailey in London, England when I was 13.

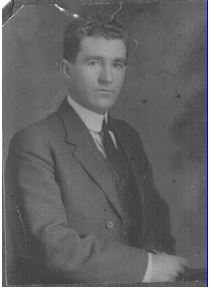

After my parents’ divorce when I was seven, I infrequently saw my Dad, but in 1958 he took me on a holiday to the capital. My dad was tall and dark and a very quiet, introspective man. I was a chatty individual but, somehow, we had a meaningful time together. At the end of our holiday, he bought me presents to take home, for my mum and sisters. He never told me he loved me, but I have a lovely memory of a man I never really understood or got to know and I like to think this was how he showed his love.

Me and Dad in London, 1958

It was a wonderful holiday, just the two of us. We visited The London Palladium Theatre and saw a show; we shopped on Oxford Street; we went to the London Zoo and Trafalgar Square where I fed the pigeons and had my portrait drawn in pencil by a street vendor, we even ventured to Soho, a notorious part of London frequented by prostitutes, drug dealers and ‘Teddy Boys. ‘So exciting’!

The Old Bailey was built in 1673, it’s predecessor, the medieval version had been destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666. During the Blitz of World War II, it was bombed and severely damaged. In the early 1950s, it was reconstructed and, in 1952, the restored interior of the Grand Hall of the Central Criminal Court was once again opened by the Lord Mayor of London. This was the Old Bailey we visited. Although the Old Bailey courthouse was rebuilt several times between 1674 and 1913, the basic design of the courtrooms remained the same. [1]

I remember the entrance to that grand hall. It was like a palace, huge and so beautiful.

The Grand Hall Inside The Old Bailey, the design mirrors the nearby dome of St Paul’s Cathedral

My Dad and I sat in the visitors’ gallery to watch a trial. I have no recollection of the details of the trial. I was too busy looking around at the wood-panelled walls, the prisoner, the solicitors, the policemen and, of course, the judge. He was dressed in a red robe and a horse-hair wig and sat slightly raised on a dais so he could gaze down upon the proceedings.

The ‘accused’ or ‘prisoner’ as they referred to him stood at the ‘bar’ or ‘dock’ with his Solicitors and Barristers (as lawyers are called in England). These 1950’s British lawyers were attired in flowing black robes like the 2018 Montreal lawyers, but with stiff-winged collars with two bands of linen in the front of the neck. They also wore wigs. And what wigs!

Type of Wigs Worn In Court

Some were white, signalling that a lawyer had just started out in his chosen profession; others were yellow with age, signalling more experienced lawyers. To me, all of the lawyers in the courtroom looked stern and forbidding.

Proceedings moved very slowly with no drama. After a few hours, I got bored and Dad and I left for lunch. But still, what a memory! And how very different was the Old Bailey courtroom compared to the modern Montreal Courthouse where informality seems to be the rule.

[1] https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/static/The-old-bailey.jsp

NOTES:

A court is held at the Old Bailey eight times a year for the trial of prisoners for crimes committed within the city of London and the county of Middlesex. The crimes tried in this court are high and petty treason, murder, felony, forgery, petty larceny, burglary, etc.

This link below shows Court Cases being heard today, at the Old Bailey.

https://old-bailey.com/old-bailey-cases-of-interest/

When I visited the Old Bailey, everyone was attired in wigs but that is now changing in England. For non-criminal cases, lawyers and judges will cease wearing wigs and I cannot help but feel sad that yet another centuries-old custom has gone.

Here is a 2 -minute read on the subject. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-britain-wigs/wigs-off-as-britain-ends-courtroom-tradition-idUSL1287872820070713

Unfortunately, now strict security measures make it impossible for visitors to go into the main body of the building. However, the clip below, shows the Lord Mayor of London opening the newly restored Old Bailey in 1952. This was the hall I entered in 1958 with my Dad.