In April, 2008 I received an unsolicited email from a Mrs. Joan Hague of Montreal with just one word in the subject line: Changi.

She had seen an article I had written about my grandmother in the Facts and Arguments1section of the Globe and Mail. She wanted to tell me about her father, Thomas Kitching, who had been interned at Changi Internment Camp in Singapore during WWII, just like my grandmother Dorothy Nixon.

I visited the gracious Mrs. Hague (recently deceased at the ripe old age of 99) only to discover something extraordinary: Mrs. H. and my own father, Dorothy’s first son, Peter, had led parallel lives!

My father, Peter, was born on October 24, 1922 in Kuala Lumpur, to a Selangor planter, Robert Nixon of North Yorkshire and his wife, Dorothy Forster of Teesdale, County Durham. Mrs. H. was born in Batu Gajah, Malaya in early November, 1922, to Thomas Kitching, the Surveyor of Singapore and his wife Nora.

As was the custom for British Colonials in the era, Mrs. H. was sent away at age six to go to school in England. She attended Harrogate Ladies’ College in North Yorkshire. My father was sent away at age five to go to a school in Maryport, Cumberland and then he went on to St. Bees prep school on the coast of Cumberland.

Mrs. Hague told me she spent her holidays with a loving grandmother in Lancashire. My father and his even younger sister, Denise, were shuttled on vacations between random relatives who resented having to care for them.

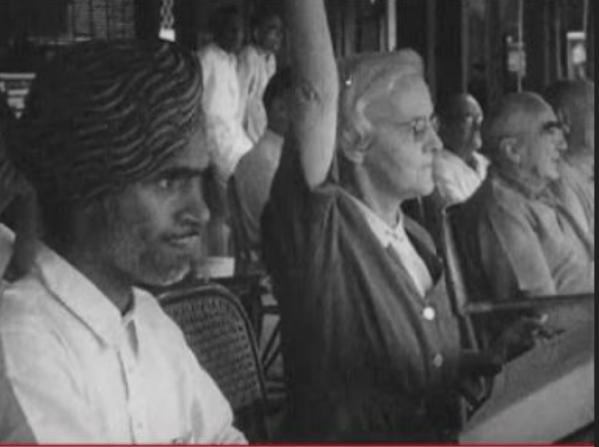

Mrs. Hague’s mother, Nora, a nurse by profession, filled the void in her life with sports, golf mostly. She also scored cricket for Singapore. My grandmother, Dorothy, became the librarian at the Kuala Lumpur Book Club and she was Selangor’s official cricket scorer.

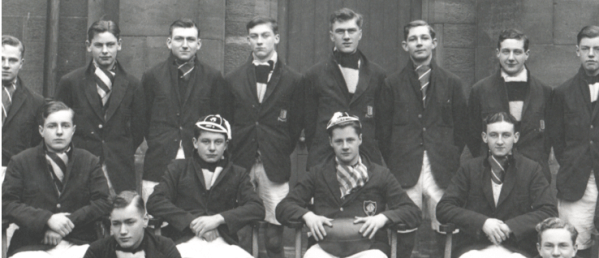

In 1939, when the phony war broke out in England, my father was about to go to Oxford. Mrs. H. was in her last year at her ladies’ college. The Harrogate students were evacuated to another town. Mrs. H’s parents, in England for a time, brought her back to Singapore because they thought she would be safer. After two years at Oxford’s St Edmund Hall (where he was awarded ‘colours’ for rugby) my father signed up with the RAF and went to train in Saskatchewan, Canada.

The Japanese invaded Malaya on Boxing Day, 1942.The Japanese planes bombed “the green” at the center of KL, the site of many government buildings. My grandmother’s library building, adjacent the legendary Royal Selangor Club, was hit. During the bombing my grandmother hid under a desk. Later, she helped dig four dead bodies from out of the rubble.

On that ominous day, Mrs. H and her mom were safely in “fortress” Singapore. They joined up as VADs, tending to the severely burned survivors of two navy ships that had been blown up by the Japanese in Singapore Harbour. Mrs. H. had a vivid memory of unfolding the hospital cots that were all covered in a sticky goo to prevent rusting.

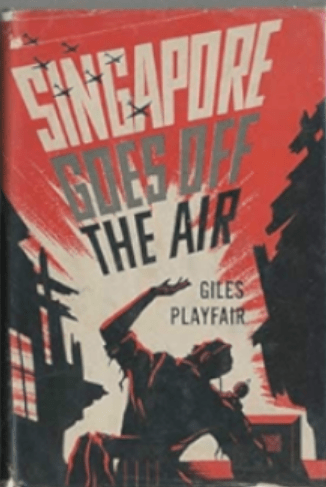

Kuala Lumpur soon fell. My grandmother was commanded to take a noisy, unlit night train to Singapore. Upon arriving, she immediately joined the ‘resistance’ at the Malaya Broadcasting Corporation.2

To everyone’s surprise and to Winston Churchill’s embarrassment Singapore soon fell as well. Mrs. H. escaped to Batavia and made it back to England but tragically Nora, her mother, took another boat, the Kuala, with 500 others including 250 women and children, and was lost at sea when her ship was bombed by the enemy.

Mrs. H. trained as a physiotherapist at St Thomas Hospital, London and volunteered at the Canadian Camp.

Mrs. H’s father, Thomas Kitching, was interned at Changi Internment Camp, as were my grandmother and grandfather, Dorothy and Robert Nixon. (Upon the fall of Singapore, Dorothy had stubbornly refused to escape to Batavia, staying instead to support wounded soldiers. A good thing, perhaps.)

Kitching died of throat cancer in the men’s section of Changi prison in 1944 but he kept a diary of his time there that was later published. For a six month period my grandmother was Commandant of the Women’s Camp and according to her own unpublished memoirs she liked sneaking into the men’s camp, which was strictly against the rules, to gather information. The men had secret radio sets, you see, and she was an amateur radio enthusiast.

On October 10, 1944 many of these men and a few women were accused of spying in the infamous Double Tenth incident and taken by the Japanese Gestapo to a room in the basement of the local YMCA to be harshly interrogated, some men horribly tortured. My grandmother stayed in that stifling, bug-infested room with the crazed, half-starved men for a month, enduring a kick in the ribs on occasion, and then she was put in solitary confinement for another five months.

She survived her ordeal, but barely.

My father, meanwhile, was posted to the Ferry Command based in Dorval, Quebec, a suburb of Montreal. A member of both the RAF and RCAF, he flew planes around the world, mostly mosquitos he told me.

In Montreal he met my mother, a French Canadian stenographer at RKO Radio Pictures probably at a party at the Mount Royal Hotel. They married after the war in 1949 once my father had finished his war-shortened math degree at Oxford.

In Montreal, my father added on a night time Commerce Degree from Sir George Williams University and a CA from McGill while working full time and raising a family.

Mrs. H. met her future husband, Mr H., the son of a prominent Westmount banker, during the war in London at a party for Canadian soldiers. The invitees brought with them a big juicy turkey apparently. The couple married in Morecambe Parish Church and moved to Montreal on the war bride scheme.

It is too bad I never got the chance to introduce Mrs. H. to my father as he succumbed to Alzheimer’s in the St. Anne de Bellevue Veteran’s Hospital in 2005. They certainly would have had a great deal to talk about!

Indeed, they may have already met. They both sent their sons to Lower Canada College on Royal Avenue in NDG in the 1960’s.

1. My Crochety Grandmother Deciphered.

2. Chronicled in a 1945 book Singapore Goes off the Air by Giles Playfair. The author wrote fondly of my grandmother, although he held the common belief (from back then) that Colonial women were indolent parvenues, ‘who would be sweeping out a four bedroom cottage back home’ were they not in Malaya attending fancy liquor-oiled soirees and waited on at home by a slew of servants.

3. Joan Hague obituary, chronicling her ‘interesting’ life with portrait young and old. I wrote this piece years ago and posted it on my personal blog after passing it by Joan Hague but also added two tidbits from her online obituary: Her marriage details and her work details.LINK HERE