Thursday, December 11, 1845, a biting easterly wind that had held Pembrokeshire, Wales, in an arctic grip for days as John O’Bray Senior, my third Great Grandfather, stepped out of his home at 14, Queen Street, East, bundled up against sub-zero temperatures, and the aftermath of a major snowstorm.

14, Queen Street, East Pennar, Wales, circa 2021

A thick layer of dry, powdery snow covered the ground—a rare sight for Wales that would linger for over a week due to the sustained freeze. (1)

John was an “old servant” of the Pembroke Royal Dockyard (the Paterchurch site). At 53, he was a master shipwright who had walked these paths since he was a twelve-year-old boy. He lived in Pennar, a district on a headland perfectly situated for dockyard workers. Pennar was one of the first residential areas to expand alongside the dockyard’s rapid 19th-century development.

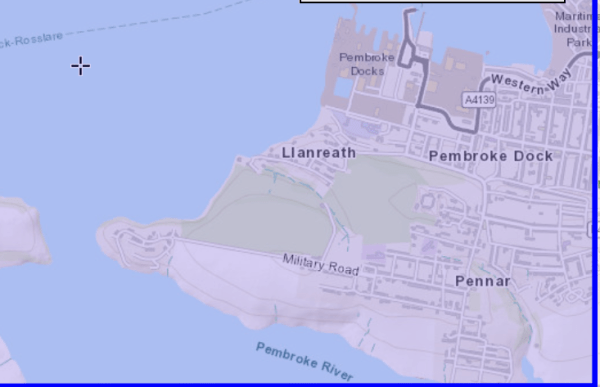

Map of Pennar and Pembroke Docks

A Lifetime of Service

Records from Richard Rose’s “Pembroke People” provide a clear timeline of John’s long career:

- June 24, 1805: John entered as a shipwright boy at Milford, aged 13. He was paid 2 shillings a day.

- July 1812: He became a full shipwright at age 21, earning 3 shillings and 4 pence a day.

- April 20, 1812: Just before his promotion, he married Eleanor (Elinor) Allen. Together, they raised ten children.

- A Lineage of Craft: John was part of a multi-generational dynasty. This trade—from shipwrights to boilermakers—continued for over 150 years, ending with my grandfather, Percival Victor O’Bray. They were the “naval backbone” of Britain from the Napoleonic era through the World Wars.

The Fatal Morning

On that freezing morning, 1845, John was working on the ‘slips’—the massive, sloping masonry platforms used to build and launch ships. At Pembroke, these were not open to the elements but were covered by enormous, echoing iron and timber roofs. Despite the roof, the dry powdery snow would have drifted through the open ends of the slips, and the east wind would have whistled through the scaffolding, coating the wooden planks in a treacherous glaze of frost.

For a significant vessel, the slip might rise 6-12 meters (20-40 feet) or more from the low water mark to the top of the slip’s working area, with the slope extending a considerable distance into the harbour (2)

The Accident

As John crossed a stage surrounding a ship’s hull, a common but deadly scaffolding error occurred. A plank had been “short planked”—it did not have a sufficient overlap on its support. As John stepped past the pivot point, the plank acted like a seesaw, tilting upward and sending him plummeting to the stone floor below.

The Carmarthen Journal (December 19, 1845) reported the tragedy:

“An efficient and industrious shipwright, named John Obrey, (sic) belonging to Her Majesty’s Dock Yard at Pembroke, fell from a considerable height into one of the building slips, and was killed on Thursday last.

To mark the esteem in which he was held by the authorities of that establishment, the Chapel bell of the Arsenal was tolled during the funeral. * It appears a plank forming one of the stages aroundthe ship’s side had not sufficient hold of the support on which it rested, and the weight tilting it up, he was precipitated into the slip, and falling on his head.***

His skull was so fractured that his brain actually protruded. His wife will, no doubt, have a pension, though the amount must necessarily be small”

* The Chapel Bell of the Arsenal tolling is a significant detail. It shows that John was not just a nameless labourer; he was a respected member of a tight-knit community. The “Arsenal” refers to the fortified nature of the Pembroke Dockyard, which was protected by a series of Martello towers and barracks to defend the valuable ships under construction. (3)

** The Pension The Carmarthen Journal’s mention of a pension for his wife, Elinor, is noteworthy. While “small,” the fact that a pension was even discussed suggests John’s “old servant” status (his 40+ years of service since 1803) granted his family a level of consideration not always afforded to Victorian labourers.

*** The Hazard of Short Planking. The description of the plank not having “sufficient hold of the support” suggests a common but deadly scaffolding error. In the rush of a busy dockyard, a plank that didn’t overlap its support sufficiently could become a “seesaw” the moment a worker stepped past the pivot point.

Also reporting was The Pembrokeshire Herald and General Advertiser, 19th December, 1845, Page 3

“A fatal accident befell one of the workmen in Pembroke Royal Dockyard last Thursday. On crossing a stage, he stepped on a plank which gave way under him, and falling into the slip upon his head, was killed on the spot. His brains were actually seen oozing through the skull. His name was O’Bray – an old servant and an active mechanic”

Those phrases, ‘brains actually protruded’, are graphic, but show the brutality of industrial work in the 19th century. The contrast between the “industrious shipwright” described in the newspapers and the brutal nature of his accident highlights the high stakes of Victorian maritime labour.

Faith and Final Rest

At the time of his death, John served as a clerk for his local church. Interestingly, he had converted to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, though he passed away before he could be formally baptised.

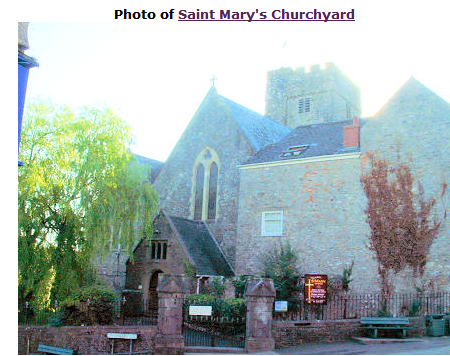

His wife’s family had roots in early Methodism in Milford and Pater, showing a family history of deep religious conviction. John O’Bray, Senior, was buried by Coroner’s Order at Saint Mary’s Churchyard in Pembroke.

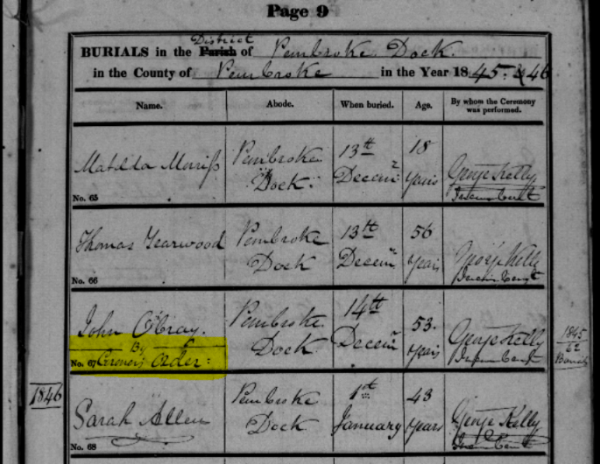

John was buried by a coroner’s order

Sources

These historical weather records below detail the cold temperatures and snow cover experienced in Milford Haven during December 1845

- Central England Temperature (CET) records and regional logs for the winter of 1845–46. Met Office Historical Weather Records / “The Climate of Pembrokeshire.”

- https://www.ice.org.uk/what-is-civil-engineering/infrastructure-projects/pembroke-dockyard#:~:text=Did%20you%20know%20%E2%80%A6%20*%20Pembroke%20Dockyard,first%20iron%20roofs%20to%20shipbuilding%20slips%20(1845).

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Royal_Navy_Dockyard

Notes:

Recorded here at https://www.cnrs-scrn.org/northern_mariner/vol03/tnm_3_1_1-43.pdf, is a historical fatality, which could be a mention of John O’Bray’s death:

“Documentary evidence from the era records instances where planks forming these stages gave way, precipitating shipwrights into the slip. One such record describes a worker falling headfirst from a stage, resulting in a fatal skull fracture upon hitting the stone floor”