Henry Boggie is my great-grandfather, but he was never really part of the family.

My grandmother, Elspeth Mill Boggie Orrock was born in 1875 in Arbroath in County Angus, Scotland. Her mother, Annie Linn Orrock, registered the birth and gave Elspeth her surname Orrock but she also gave Elspeth the name Boggie. The registration notes that Elspeth was illegitimate as her parents were not married.1

In 1881, when Elspeth was 6 years old, Annie Linn, still residing at 32 East Mill Wynd where she had given birth to Elspeth, instituted a civil paternity suit against Henry Boggie in the Sheriff Court. On 11 September 1882, a decree was issued by the Sheriff Court, stating that the birth registration be corrected to include Henry Boggie as Elspeth’s father.2

Paternity cases were usually attempts to make the father pay child support and we can assume that this is probably why Annie Linn sued Henry for paternity.3 There is no evidence that Henry and Annie every lived together.

The censuses show that Henry lived with his mother until at least 1891. He worked as a mason and remained in Arbroath his entire life. He died fairly young, at 53. The registration of his birth says that he was single.4 It is unlikely that he fathered any other children.

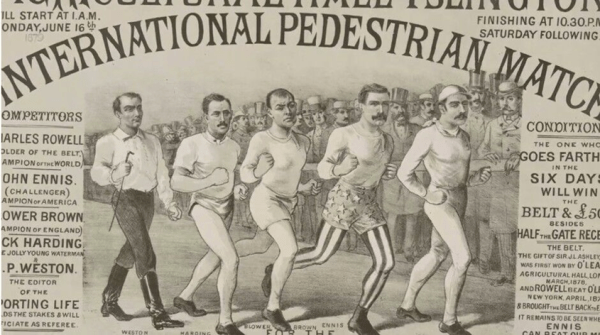

The records indicate that Henry led a quiet life, living in the same city all his life. However, Henry did practice an unusual sport, pedestrianism. In the 19th century, he would have been called a ped. At the time, pedestrianism was popular in Scotland and elsewhere. The six-day, 450-mile race usually began on a Sunday at 1:00 a.m. It started after midnight on Sunday because public amusements were prohibited on Sundays. The athletes walked for six days in a row, in a circle and had to complete the 450 miles. They could run, walk, or crawl. They ate, drank, and napped in little tents at the side. 5

The walking matches were a spectator sport, with music and refreshments. It was like a fair. Gambling was also part of the attraction. There were lots of possibilities to place bets, such as the first pedestrian to drop out or the first to achieve a set number of miles. At the time, champagne was considered a stimulant. Some of the trainers (yes, they had trainers) would encourage the participants to drink copious amounts of it.6

Henry seems to have participated in several pedestrian tournaments. He was described as one of the “crack” walkers who participated in the Dundee tournament when he joined the Aberdeen Walking Match in December 1879. It took place in Cooke’s Circus, an equestrian establishment so we can assume that the participants walked around the equestrian arena. Prize money totalled £40 (about £6,000 today) and the winner won the champion belt of Scotland.7

On March 8, 1880, Henry competed in the Perth Grand Pedestrian Tournament. The thirty-three participants hailed from England and Scotland. The format of this tournament was that the men would walk or run between eleven o’clock in the morning and stop at eleven o’clock in the evening. First prize was £25 (about £3,800 today). Jostling, hindering another participant, or using bad language would result in disqualification. Reserved seats were two shillings, second seats were one shilling, and third seats were a sixpence. A musical band was in attendance. Gambling was prohibited.8

The newspaper articles that list Henry’s participation in the Dundee, Perth, and Aberdeen tournaments are just a glimpse into this interesting sport. Not only did the participants travel to compete in these tournaments, the six-day races would have been quite exciting and exhilarating. There is no indication whether or not Henry ever won prize money, but still, he was a “crack” competitor.

- Scotland’s People, National Records of Scotland, Statutory Registers of Birth, 1875, District of Arbroath, County of Forfar, Elspeth Mill Boggie Orrock, retrieved 12 January 2018.

- Register of Corrected Entries for the District of Arbroath in the County of Forfar, dated 11 September 1882, directing that the defendant, Henry Boggie, Mason, should appear on the registration of birth of Elspeth Mill Boggie Orrock, in possession of author.

- Traces. Uncovering the Past, Tracing the Fathers of Illegitimate Children in Scottish Court Records, 3 December 2020, https://tracesmagazine.com.au/2020/12/tracing-the-fathers-of-illegitimate-children-in-scottish-court-records/, accessed 22 January 2024.

- Scotland’s People, National Records of Scotland, Statutory Registers of Death, 1905, District of Arbroath, County of Forfar, Henry Boggie, retrieved 22 January 2024.

- BBC, The Strange 19th century sport that was cooler than football, Zaria Gorvett, 28 July 2021, https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20210723-the-strange-19th-century-sport-that-was-cooler-than-football, accessed 22 January 2024.

- NPR, In The 1870s And ’80s, Being A Pedestrian Was Anything But, 3 April 2014, accessed 23 January 2024.

- Aberdeen Press and Journal, 29 December 1879, page 4, accessed through British Newspapers on Findmypast, 23 January 2024.

- Dundee Courrier and Angus, 8 March 1880, page 1, accessed through British Newspapers on Findmypast, 23 January 2024.