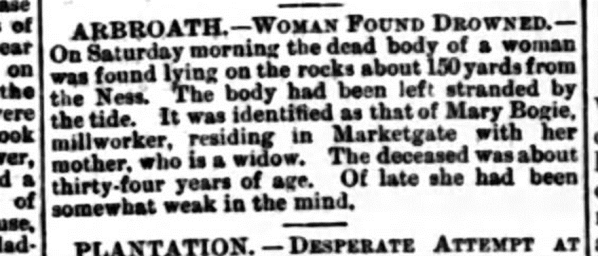

“Of late she was somewhat weak in the mind.”

This sad sentence concludes the obituary of Mary Boggie who died by drowning on September 6, 1884 when she was just thirty-four years old.1 Her death was a suicide and this one sentence tries to explain why. Of course, no one will ever know why she jumped off a cliff into the cold and inhospitable waters of the North Sea. What we do know is that it was a desperate and definitive act.

Mary Boggie was Henry Boggie’s sister. Henry, my great-grandfather, was taken to court by my great-grandmother, Annie Orrock, in a paternity suit. He never lived with Annie and, as far as I know, did not participate in bringing up my grandmother, Elspeth Orrock. Mary and Henry were the only children of George Boggie and Elspeth Milne. The Boggie family lived all their lives in Arbroath, Scotland. Arbroath is a coastal town located on the North Sea, about 26 km northeast of Dundee and 72 km southwest of Aberdeen.2 In the 19th century, Arbroath experienced a rapid growth in population with an influx of workers needed for the expansion of the jute and sailcloth industry.3 George was a member of the merchant navy and would have been absent from home most of the time. Both Mary and Henry lived at home, with their mother, all of their adult lives.

The registration of Mary’s death indicates that Henry was one of the “finders” of her body. The cause of death was “mental disturbance.”4 Who knows how long he and others were searching for her? She was found at the bottom of Whiting Ness, a cliff in Marketgate, Arbroath.

In 1884, sudden deaths in Scotland were referred to the Procurator Fiscal, known in other jurisdictions as the public prosecutor. The inquiry found that that the cause of Mary’s death was drowning and that she had committed suicide. The corrected entry notes that Mary had not been certified, meaning that she had never been certified as being mentally ill.5 The newspaper article implies that she was suffering from some mental affliction. And this is in accordance with the thinking at the time; that suicides were thought to be temporarily insane, thus being innocent of “self-murder.”6 Committing suicide was not considered a crime in Victorian and Edwardian Scotland. Citizens were free to take their own life, but it was assumed they would be answerable to God. This was not the case in England and Wales, where suicide was decriminalised only in 1961 with the passing of the Suicide Act. Prior to this, anyone who attempted suicide could be imprisoned and if they were successful and died, their families could be prosecuted. 7

No matter what the attitudes towards suicide at the time, Mary’s death was a tragedy. She could have been suffering from any number of mental or physical afflictions that would cause her to take her life. We can only imagine the anxiety and agony that Henry and Elspeth were feeling as people were desperately trying to find her. The trauma of finding her must have been almost more than Henry could bear. It would then be up to him to tell his mother. The suddenness and the violence of Mary’s death would have been a shock and difficult to understand. Henry and Elspeth were faced with an investigation and they would have had to deal with the press. Sadly, they may have had to deal with shame and the stigma of mental illness in the family.

- Obituary for Mary Boggie, Glasgow Daily Mail, 8 September 1884, newspapers.com, accessed 23 May 2024.

- Wikipedia, Arbroath, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arbroath, accessed 29 May 2024.

- Ibid.

- Scotland’s People, Registration of Deaths 1884, Mary Boggie, accessed 3 April 2024.

- Scotland’s People, Page 105, Register of Corrected Entries, Mary Boggie, signed by the Procurator Fiscal’s Office, 24 September 1884, accessed 3 April 2024.

- Shiels, Robert, The Investigation of Suicide in Victorian and Edwardian Scotland, Dundee Student Law Review, Vol. 5(1+2), No.4, https://sites.dundee.ac.uk/dundeestudentlawreview/wp-content/uploads/sites/102/2019/09/R-Shiels-No-4.pdf, accessed 27 May 2024.

- Wikipedia, Suicide Act 1961, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Suicide_Act_1961, accessed 28 May 2024.