In the 1871 census in the United Kingdom, categories of disability were added to the census questions. These categories included the deaf and dumb, blind, imbecile or idiot, and lunatic.1 Imbecile, idiot, and lunatic are pejorative terms today but in the 19th century, they were medical terms used to indicate mental health conditions. Idiots and imbeciles had learning disabilities. Lunacy was a term used broadly to denote anyone with a mental illness.2

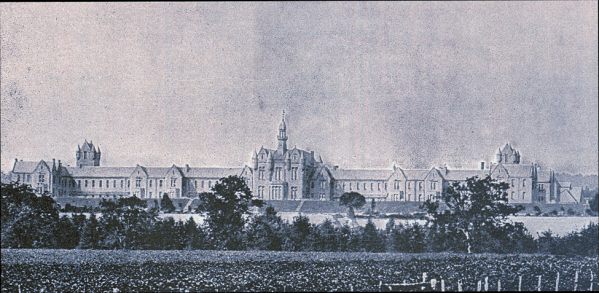

James Kinnear Orrock, my 2X great-uncle, was committed to the Dundee Royal Lunatic Asylum on December 9, 1888. Superintendent James Rorie declared that he was a pauper and that he was delusional. James’ mother, Mary Watson, my 2X great-grandmother, requested that he be committed.4 Not unlike today, the police were involved. A constable declared that he had been violent and incoherent. It is obvious from the notice of admissions that James was experiencing psychotic episodes.

James was just 30 when he was admitted to the asylum. Sadly, he remained there until his death in 1930 when he was 72.5 It is distressing that he lived in this institution more than half his life. While little was known about mental illness at the time, the asylum offered the patients safety and hope. Specialist registrar Amy Macaskill states “What is clear is that they wanted to offer a degree of care and protection and containment for people who were causing difficulty at home and were in some level of distress.”6 The asylums cared for people who were depressed, anxious, delusional, as well as those suffering from other conditions such as epilepsy, alcoholism, and syphilis.7

The Dundee Royal Lunatic Asylum had separate quarters for men and women. The pauper wards for men each had a day room, with a number of single rooms with windows overlooking the airing court. The windows provided the only ventilation. The rooms were not heated but there were open fire places in the corridors. There were weaver shops in a separate building where some patients made packing cloth. Male patients also did stone breaking and some worked on the grounds. They were paid with tobacco and beer. There was a billiard room and dancing parties for the patients, attended by both men and women. A chaplain provided services on Sundays.8

When James was admitted, he was certified a pauper lunatic. This certification gave him access to psychiatric care, but it does not necessarily mean that he was a pauper. His admission records indicate that he was a seaman and he could have been gainfully employed. The Board of Governors of the asylums assessed each patient’s finances. If any financial assistance was required, then the patient was declared a pauper. If the patient or their family was assessed as being able to entirely finance their own care, they were classified as private patients. Private patients benefitted from better food, were able to wear their own clothes, and could be discharged if the person paying for their care wanted their discharge. Unfortunately, while a technical and legal label, the term “pauper lunatic” carried a stigma and deterred people from seeking help.9

We have come a long way in our care for those suffering from mental illness since the 19th century. The Lunacy (Scotland) Act 1857 formed mental health law in Scotland from 1857 until 1913. Its purpose was to provide official oversight of mental health institutions and to ensure that they were adequately funded.10

- Scotland’s People, Census Records, 1871 Census, https://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/research/guides/census-records/1871-census#1871%20instructions, accessed 1 November 2023.

- Historic England, Disability History Glossary, https://historicengland.org.uk/research/inclusive-heritage/disability-history/about-the-project/glossary/, accessed 1 November 2023

- Notice of Admissions, Royal Dundee Lunatic Asylum, Notice of Admissions, James Orrock, retrieved 22 March 2023

- James Rorie went on to write the History of the Dundee Royal Lunatic Asylum

- Scotland’s People, 1891, 1901, 1911, 1921 censuses, John Orrock, accessed 20 November 2023.

- BC News, Archives reveal life in Edinburgh and Inverness asylums, 7 January 2013, https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-scotland-20938462, accessed 21 November 2023.

- National Records of Scotland, From the NRS Archives, Servicemen in Scotland’s Asylums, 1918, 10 January 2019, https://blog.nrscotland.gov.uk/2019/01/10/from-the-nrs-archives-servicemen-in-scotlands-asylums-august-1918/, accessed 22 November 2023.

- Scottish Indexes, Institution Information – Dundee Royal Infirmary, https://www.scottishindexes.com/institutions/19.aspx, accessed 22 November 2023.

- Royal College of Psychiatrists, Pauper lunatics were not paupers, 23 February 2022, https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/news-and-features/blogs/detail/history-archives-and-library-blog/2022/02/23/pauper-lunatics, accessed 21 November 2023.

- Wikipedia, Lunacy (Scotland) Act 1857, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lunacy_(Scotland)_Act_1857, accessed 22 November 2023.