The internet and social media have changed our lives, allowing us to connect to new friends and reconnect to old ones to celebrate our victories and lives. I recently experienced this first-hand.

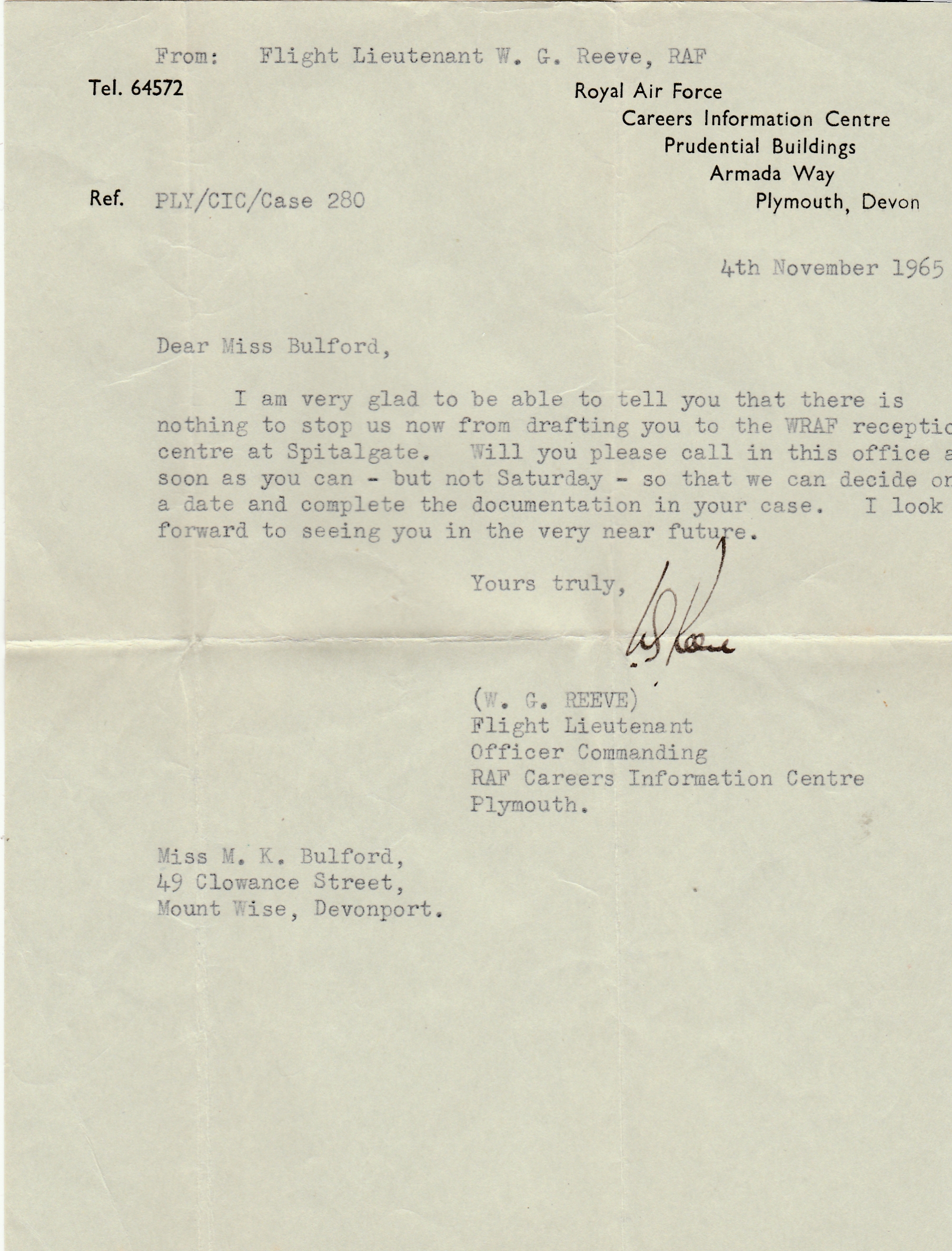

Last September, I received, out of the blue, an email message from a complete stranger because he read a few of my stories on Genealogyensemble.com about my time in the Women’s Royal Air Force (WRAF).

George Cook, an archivist for the Trenchard Museum, which is based at RAF Halton was gathering information on the MTE – Medical Training Establishment – and happened upon the story of my time there. He recognised the man in one of my photos that went with the story.

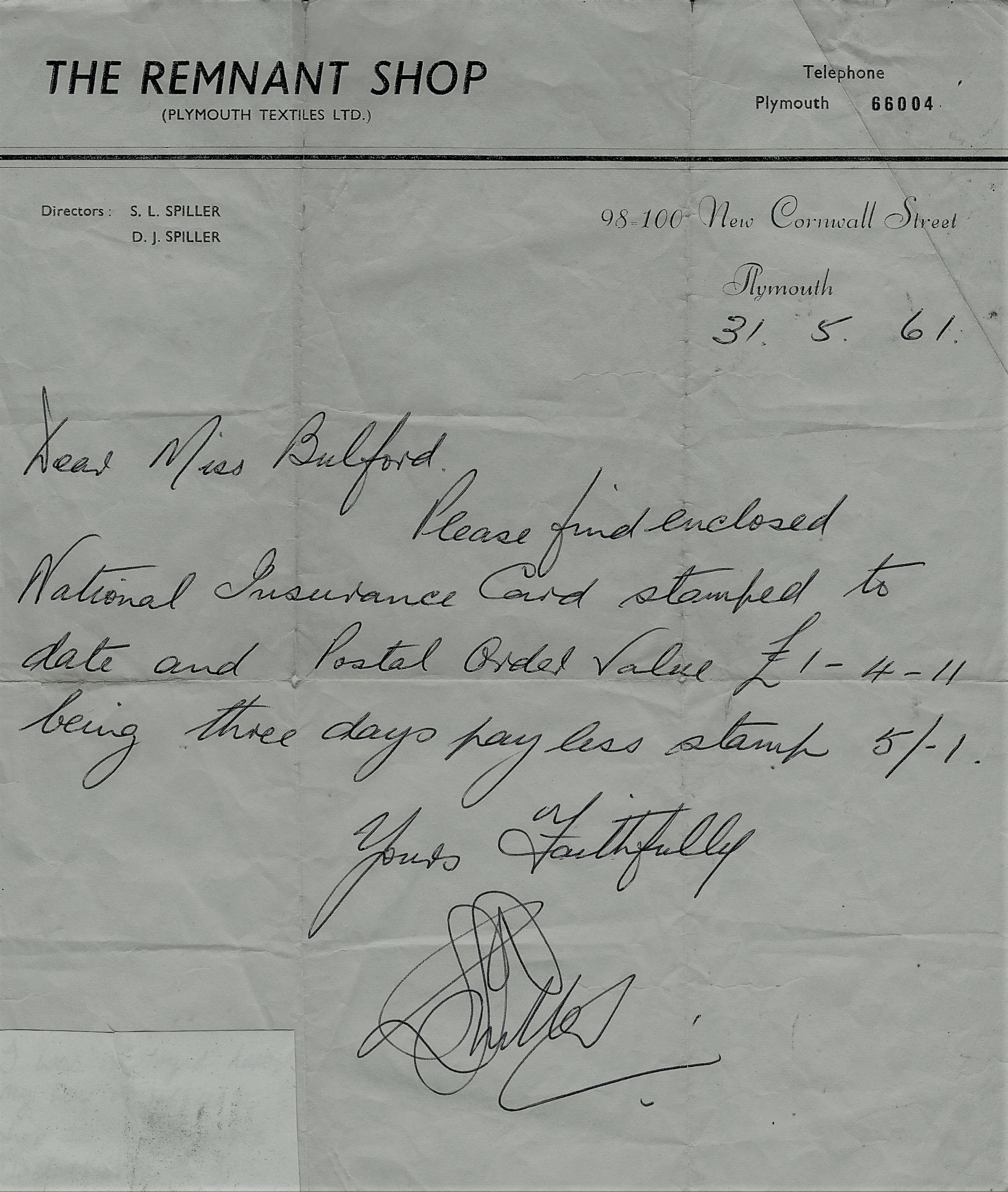

“Purely by chance, I had the opportunity to read “Dear Miss Bulford” and I was compelled to follow up on Marian’s story of life in the RAF in the 1960s,” he said in his email.

‘You will appreciate my surprise when on reading part 4, I recognised the young gentleman who became her husband. John and I joined the RAF in September 1964 as admin apprentices at RAF Hereford. Not only did we do our square bashing together for 12 months but we were both posted to RAF North Luffenham in Rutland in 1965”

So, of course, I had to find out more. Let’s begin at the beginning of this intriguing tale, as told to me by George in his letter and by my very surprised husband.

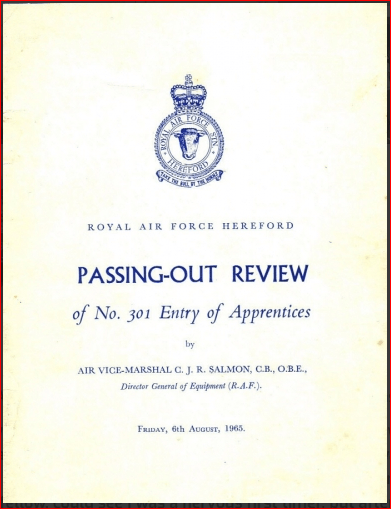

At the end of August 1964, my husband John Clegg was only 16 years old. He says he remembers standing on Liverpool Station on Lime Street England, waiting for a train to Herefordshire. He had left school in July 1964 and was headed off to join the Royal Air Force at RAF Hereford to enter a one-year Administrative Apprentice training course as part of the 301st cohort known as an ‘entry’ (1)

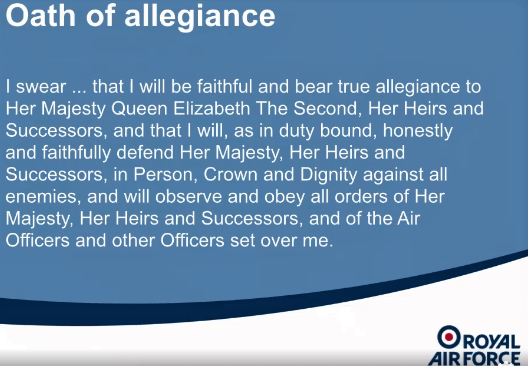

A week later, on the 2nd of September 1964, he took the Oath of Allegiance to Her Majesty the Queen.

This committed him to serve 12 years in the RAF. One small point not clearly explained to an eager 16-year-old was that his 12 years of service wouldn’t start until his 18th birthday, meaning that the RAF had him for two extra years (14 in total)!

The boys in the administrative programme numbered approximately 40 per entry and were divided up into two dormitories of 20 per room. The training period consisted of daily classes for administrative procedures which would, on successful completion, quality John as an Administrative Secretarial Clerk. In addition, he learned personal discipline and stories about life in the RAF, including its history.

At that time, students were also taught to type on mechanical typewriters. John says that that training prepared him for the future introduction of computers John can still type 55 words a minute, the speed the boys were trained to do. George sent us this photograph of the typewriter they learned on.

George Cook also apprenticed at RAF Hereford and he and my husband were alphabetical order billeting, which meant they ended up in the same room. They became friends.

John remembers George as a wonderful artist. He told me, that one drawing, in particular, stood out. It was a haze of charcoal until you stepped back and there appeared the face of Dusty Springfield a very popular singer in the England of the 1960s. John always remembered that drawing and the quiet talent that was often on display from George.

Whilst there, John and George made many friends with boys from different parts of the UK and from different backgrounds. After a year of close contact and demanding discipline, they forged friendships and operated as a group. At the end of the year-long course, trainees graduated as Senior Aircraftmen and had their passing out parade then they were posted to their stations where they became part of an administration team. Afterwards, they were to be posted to different parts of the country. Many never saw each other again, but that’s not what happened with John and George.

Instead, they got their first posting together to RAF North Luffenham in Rutland. This area is very ancient and first mentioned as a separate county in 1159, but as late as the 14th century referred to as the “Soke’ of Rutland’, and in the Domesday Book as “A detached landlocked part of Nottinghamshire” (2)

George was in the Station Sick Quarters teaching the Nursing Attendants to type, whilst John’s first assignment at North Luffenham was as a clerk in the Motor Transport section and later to the Ground Radio Servicing Centre. They were responsible for the reparation of Radar and Radio facilities in the UK. At a later point, he worked in the General Office and helped prepare airmen for overseas posting.

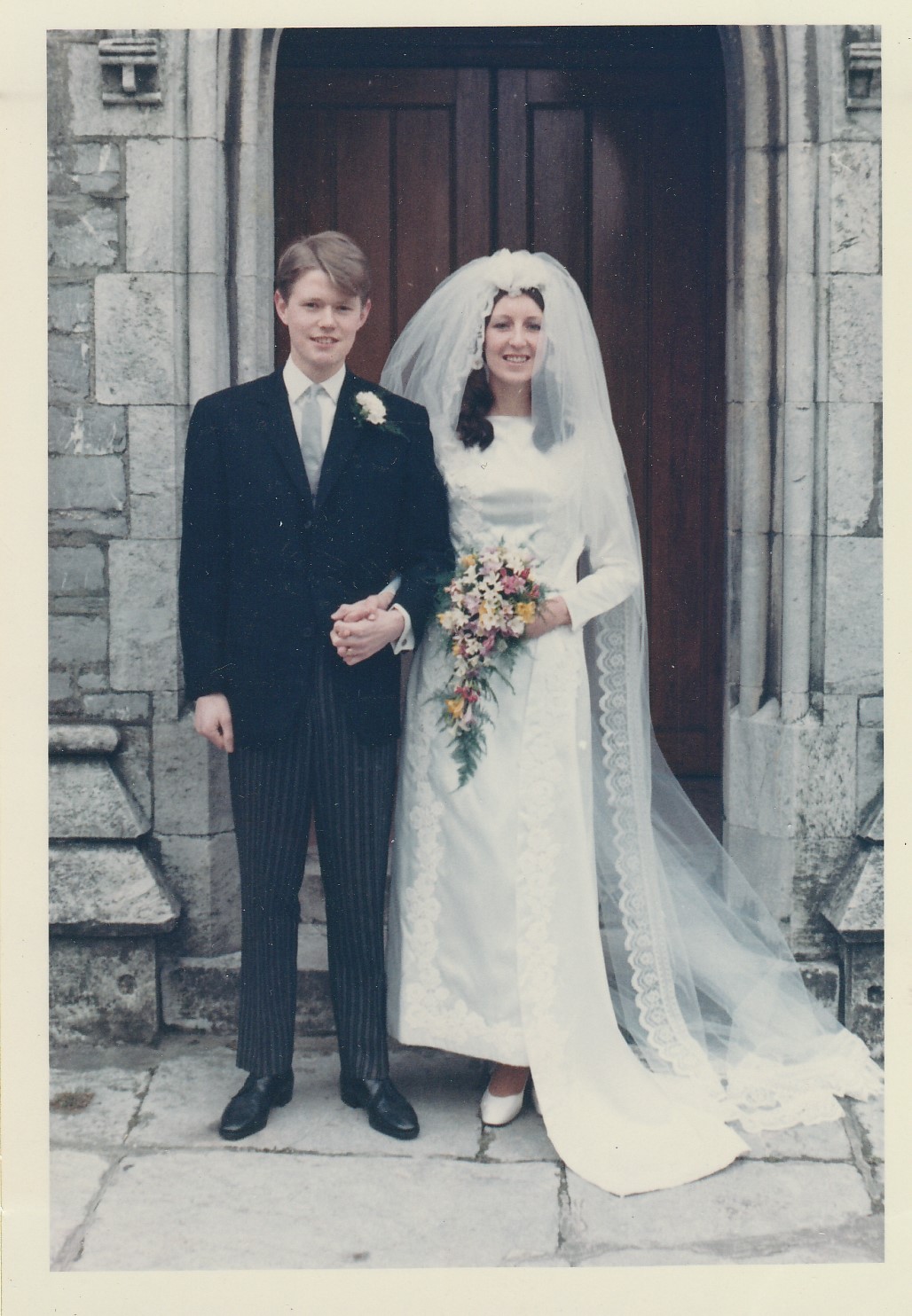

After a few years at RAF North Luffenham, John applied for a position on VIP duties, as a clerk on the staff of the Air Officer Commander in Chief at RAF Upavon in Wiltshire England where, shortly after his arrival, he met…….me!

**(Read my adventures and how I later met my husband of 53 years at RAF Upavon below)

Fast forward 60+ years and George read my story about my time in the RAF. Here’s what he told me about his experience

“During the 2 years there, I also worked in the Station Sick Quarters as the admin support to help the Nursing Attendants learn how to type at the mind-boggling speed of 15 wpm! We went our separate ways when I was posted to Singapore in 1968 but I do recall being told that John had re-mustered in the trade of air cartographer and was serving at AIDU RAF Northolt.

So, how did I come to read Marian’s stories? I work as a volunteer at the Trenchard Museum RAF Halton as an archivist and one of my tasks is to look into the history of the station.

Most people associate the station as the home of Number 1 School of Technical Training and the Trenchard Brats, young engineering apprentices who entered into a 3-year apprentice scheme set up by Lord Trenchard in 1922. What many people seem to overlook is the amazing medical history of the unit particularly the hospital, Institute of Pathology and Tropical Medicine and of course the Medical Training Establishment (MTE) Marian refers to.

Marian, I loved your stories and you have made an old man very happy learning of my old pal John. I hope that you are both well particularly in these troubled times”

I read his email with great excitement. I called my husband to come and read THIS!!!

When he read it he could not believe it was from the same George whom he knew all those years ago when they served together as Administrative Apprentices.

George Cook is now a volunteer Archivist at the Trenchard Museum at RAF Halton and also assists with the guided tours of the Halton House Officers’ Mess. (3) (4)

An exchange of emails reveals that George has led a full and varied career in various positions of leadership in the RAF. John served 12 years and then served many years in the airline industry in Genéva, Switzerland and Montréal, Canada where we now reside.

How amazing is the speed of technology the internet and social media? I will always be grateful that it allowed George to read my stories, and John to reconnect with his friend after so many years.

SOURCES

(1) https://rafadappassn.org/the-raf-administrative-apprentice-scheme/

(2) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Rutland

(3)https://www.trenchardmuseum.org.uk/

(4) https://www.forces-war-records.co.uk/units/595/raf-halton

Four stories of my adventures in the WRAF – Women’s Royal Air Force.

Part 1 https://genealogyensemble.com/2020/01/02/dear-miss-bulford/

Part 2 https://genealogyensemble.com/2020/04/22/dear-miss-bulford-part-two/

Part 3 https://genealogyensemble.com/2020/04/29/__trashed-4/

Part 4 https://genealogyensemble.com/2020/07/01/dear-miss-bulford-part-four/

RAF Upavon Crest

RAF Upavon Crest

Our first home together, Dairy Cottage

Our first home together, Dairy Cottage