Amarilda

It is easy to look up a French-Canadian catholic lady for three main reasons:

1. The documents are centralised in the archives: no need to know the church or village name.

2. Women always use their birth family name in records, from birth to death. There may ‘’wife of’’ or ‘’widow of’’ also included.

3. Parents are listed on the marriage record.

You can use the Drouin collection of books, one for men and one for women, with marriages 1760-1935, or online Drouin or Ancestry or Family Search at home or at the Quebec family History Society.

Beginning of the Journey

When I started my research, I had my mother in law’s parents and their wedding. Her grand-father Benjamin Simard’s wedding I found : to Amarilda Desbiens, August 17th 1887 in Baie-St-Paul .

Amarilda was the daughter of Joseph Desbiens and Louise Bouchard, and on I went in an afternoon, all the way up the tree to France.

Then, with different resources I found birth and death certificates, but no birth date for Amarilda. Even in books where they would list her whole family, ancestors and descendants, there was a marriage and a death, but no birth for her.

At the Société d’histoire de Charlevoix, her card was in a collection of funeral cards. I got an approximate date of birth of 1866 from the information: died May 11th 1944, at 77 years and 9 months.

All her sibblings were baptised at Les Eboulements and her father in Ile-aux-Coudres. At the local Quebec Archives Depot of Charlevoix I look at the microfilmed birth registers for 1865, 1866, 1867. No Desbiens birth .

At Baie-St-Paul and Les Eboulement cemeteries: no tombstones for the family.

Les Éboulements

First turn up a mountain road

A friend told the family that Amarilda was adopted and from Scotland. She was supposed to be a Donaldson or Danielson, but I found that her sister married one, nothing about Amarilda.

My mother in law said Amarilda was a really cold and distant grand-mother, sitting very upright in her chair, a cameo at her neck and a blanket on her knees. She only had three kids.

When she was young, my mother in law’s sister was so blond with blue eyes, she was told she was Irish by the neighbours.

At BAnQ: census on microfilms:

1871, She is not listed with her family. She probably hasn’t arrived yet:

1881, still not there:

1891, she is married and with her husband:

So she must have been adopted when she was older than 15 years old.

I started looking up immigration history books, lists… To no avail.

Even now, when I look up online Ancestry, Drouin or Family Search : marriage records only for dear Amarilda.

Now I knew she was laughing watching me go in circles. Every place I went, every book I got my hands on, I looked her up. Not a word on her birth.

Final sretch

I finally tried at Baie-St-Paul presbytery. In the filing cabinet, the individual’s cards are grouped by family. With husband Benjamin and kids, Amarilda’s card, with three dates: birth, marriage and death! I then looked up her parents, Jospeh Desbiens and Louise Bouchard cards as a group, with their children: there she was, born not in Les Eboulements, but in Baie-St-Paul: MARIE DESBIENS. ONLY Marie! Baptised 9 aout 1866

Baie-St-Paul register, 1866

Before she was five, she was adopted by the neighbour Charles Potvin, a baker and merchant, and wife Marie Filion.

She married Benjamin Simard August 17th 1887 in Baie-St-Paul.

Benjamin Simard, merchant

They had 10 children:

7 died young or at birth, Ambroise died at 18, Florence and Charles became adults.

Back L. to R.: Daughter Florence, Amarilda, X. Son Ambroise sitting in front

Amarilda’s eldest son, Charles, took his name from his godfather: Amarilda’s adoptive father.

Charles Simard with mother Amarilda

Charles Potvin being a merchant, maybe Benjamin Simard even took over his store.

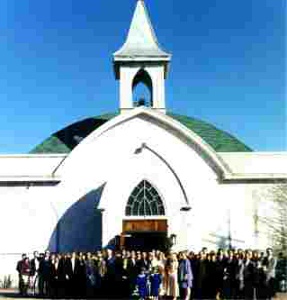

The store of Benjamin then Charles Simard, across from the church in Baie-St-Paul

Looking in the rearview mirror

All those little clues at first could not be taken for proof, but I did keep them on the back burner.

No Scottish, no Irish, not adopted INTO Desbiens family but adopted OUT to a Potvin family. Still I learned a lot even if side tracked.

I find her birth and death dates in Death Index Quebec 1926-1997 but no place of birth.If I had looked up the 1866 Baie-St-Paul register, page by page, I would have found a baby girl born to those parents in August 1866.

1. Census: 1871 she is not there, not because she has not joined the family, but because she has already left it, for…the neighbour: Charles Potvin and who will not children of their own.

When you look at the ditto signs before her name on the census, there is a very nicely formed beginning of a D for Desbiens ( just like her Desbiens family above), it stops, and dittos are put in, saying she’s a Potvin.

2. On the baptism certificate of Marie Aurélie Amarilda AKA Florence, Amarilda Desbiens Potvin is the mother

3. At Amarilda’s wedding, Charles Potvin is her witness.

If you look at the line where he is mentioned, ‘’friend of bride’’ is written over a few words that were already written. Father? Adoptive father?

4. Charles Potvin and Marie Filion are godfather and godmother of Charles Simard, first surviving son of Amarilda and Benjamin.

The road up ahead

Why was she adopted?

The first of Amarilda’s siblings was born in 1850, they were 10 children in total, and twins were born in 1863. Maybe mom was getting tired and needed help. Maybe she was sick. Or the twins were a lot to take care of, and she was pregnant with her last child who was born in 1869. Or they took her in when her mom gave birth to the last one? Charles Potvin, no kids, baker and merchant he was probably better off than his neighbours. In the area, in those days, many well off families would pay for less fortunate children’s education, or adopt them. Charles, once a father, paid for education for quite a few children of Baie-St-Paul also.

Eventually, Zoe Potvin, Charles’ sister, even married Eusebe Desbiens, Amarilda’s brother.