Dr. Henry Portrait.

He looks like one of the clan in the snapshot, with a trim athletic body, a handsome, rugged face, full-lips, sturdy chin, prominent brow over deep set eyes. He is confident in his posture as well as a snappy dresser.

He is Dr. Henry Watters of Kingsbury, Quebec and Newton, Massachusetts, first cousin to my husband’s grandmother, Marion Nicholson, the son of her Aunt Christina on her father, Norman’s, side.

That also makes him first cousin to Herbert Nicholson, Marion’s older brother. And although the two young men resembled each other in build and facial features, they could not have been less alike!

Dr. Henry , by all accounts, was a near-perfect man, a high-achiever, a man who rose to the top of his profession at the Newton Hospital near Boston, but who remained devoted to family (and that includes his cousins) throughout his life.

Despite his busy vocation, he corresponded with all of his extended family, regularly, with letters than demonstrated uncommon empathy. When writing his youngest cousin, Flora, who apparently had complained of boy troubles in her letter, “I don’t have much experience in these matters, but I can only say, if he doesn’t want you, he isn’t worthy of you.”

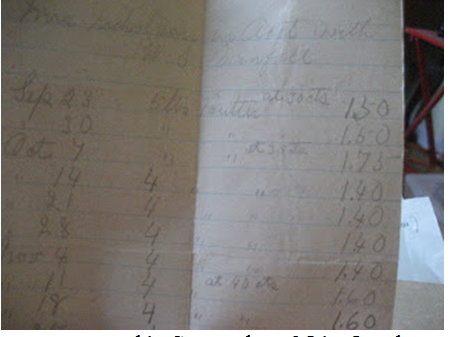

Herb, well, what can I say? As the only son of Norman and Margaret Nicholson of Richmond, Quebec, great things were expected of him. A whopping FIVE dollars was put aside at his birth in 1885 to start a bank account for his future medical career. But, upon graduation from St Francis College in 1905, he went to work as a clerk at the Eastern Townships Bank.

A ladies man and/or a gambler, Herbert immediately got into debt, borrowing money off all of his relations, until, in 1910, he got into such a desperate situation that he filched 60 dollars from the till at work.

Herbert didn’t go to jail: The Nicholsons were too well connected for that, but even Norman’s patron, E.W. Tobin, the Liberal MP for Richmond, Wolfe, couldn’t help Herbert’s cause.

Herbert was forced to skulk out West. His already cash-strapped dad had to come up with the huge sum of 500 dollars to help pay his sons debts and travel expenses.

Herbert was a teeny bit ashamed. “Don’t tell anyone where I am,” he wrote to his parents from Saskatchewan, where he was staying with Norman’s former partner in the hemlock bark business.

Out West, Herbert worked in a series of jobs in, yes, banking, then insurance, and then with a the farm equipment company, Massey-Harris.

At one point he devised a scheme to dupe immigrant farmers out of their hard-earned cash.

“I also made a 100 dollars yesterday in the shape of a man’s note due in a year’s time. I sold a threshing outfit that I repossessed from a party that could not pay for it. For 3300 and as there was only 3000 against the rig to the company; I am 300 dollars to the good. In doing this I had to divide up with two others who assisted me and knew what I was doing so we get 100 each. Have to keep these things quiet, of course.”

Herb’s letterhead from 1911-12 illustrating his roving ways

His other letters home were full of complaints about his workload, the freezing cold weather, etc. – and no shortage of insights into how capitalism works. “You have to already be rich to get rich out here,” he said.

Later, Herbert settled down in ‘real estate’ in Vancouver, got married twice to wealthy women, and then moved on to California. He died in 1967, childless.

Beside his name in the Nicholson family genealogy it says “Successful Banker.” sic.

Dr. Henry ,whose dad, Alexander Watters, was a Kingsbury, Quebec farmer, never married. Henry employed his younger sisters, Christina then Anna, as his housekeeper in his comfortable clapboard Colonial in Newton, Massachusetts.

Henry may not have been a ladies man in the usual sense of the word, but he certainly had a way with the young ladies in his family. In the 1910 period, he indulged the Nicholson women no end with trips to Wellesley College in his flashy Stanley Steamer, with sea-bathing at Nantucket, box seats at Red Sox games, theatre plays, and dinners at the posh Windsor Hotel in Montreal, when at home visiting.

His younger sister, May, got new shirtwaist suits and fancy hats from him as gifts on a regular basis. Henry once used his vacation time to drive his Aunt Margaret up and down the E.T to visit old friends.

And much to his Uncle Norman’s admiration, he paid his own father, Alexander, a trip “home” to the Old Country in 1911. “Not many sons would do that,” wrote an envious Norman to his wife.

Unlike Herbert, who found nothing good to say about any of his employers, the banks, the railway or insurance, Dr. Henry never complained about work as a doctor and surgeon in his letters to family, even when suffering from a fatal disease at a relatively young age.

From his obituary in the New England Journal of Medicine: “When stricken with what he knew meant the shortening of his days and the limiting of his activities, he carried on cheerfully and uncomplainingly. He was the friend as well as the associate of those with whom he worked, the friend and the physician of his patients.”

Dr. Henry died 1937 and is buried at home, of course, in the clan cemetery in Melbourne, Quebec. Herbert died in 1967 and is buried somewhere in a Long Beach cemetery. His last visit home to Richmond was in the 1920’s.

Herbert Nicholson 1910ish

The information comes from the Nicholson Family letters of the 1910 period. The Watters clan of Kingsbury, Quebec is written down as Waters on the 1911 Canadian Census. Henry had a younger brother, William, who died in 1910. A photo on Ancestry claims this 21 year old William is an MD too. He must have been a recently graduated one, or still a student.

I have a short obit cut out left by the Nicholsons. It says the family is shocked at William’s death in Montreal, but nothing else. A man could catch a cold and die in a day in those days, but this very short obit suggests something else more nefarious.

Below: 1911 census showing Herbert Nicholson living in a boarding house in Qu’Appelle Saskatchewan, with two recent immigrants, one from Germany, one of Scotland (a bartender, no less) and a female (!!!) stenographer. His temperance-minded parents would have passed out, had they known.

*This post was originally published on Writing Montreal, my blog.

![orchard[1]](https://genealogyensemble.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/orchard1.jpg?w=474)