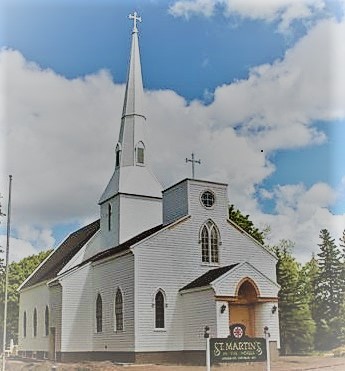

… and now his church celebrates its 200th Anniversary in 2023

(upcoming celebration details below)

The deed described the property as “a commodious estate upon the outskirts of the thriving town of Halifax, in the Colony of Nova Scotia, Canada”. Imagine William’s surprise to arrive in Halifax in February to discover that “outskirts” meant a 200-mile hike through thick forest and deep snow!

My great-great-great grandfather, William Hanington, was born in London, England, in 1759. As the son of a fish dealer, he trained as an apprentice to the Fishmonger’s Company but became a freeman in 1782. Two years later, at the age of 25, this adventurous young man paid £500 sterling for 5,000 acres of land “near” Halifax, Nova Scotia, from Captain Joseph Williams.

After the initial shock upon their arrival, William and his companion found an Indian guide, loaded all their worldly belongings onto a hand sled, trudged through the snow, slept in the open and finally arrived in bitterly cold Shediac in March 1785. His discouraged companion quickly returned to Halifax and sailed back to England on the first available ship!

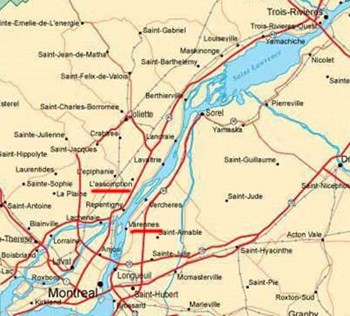

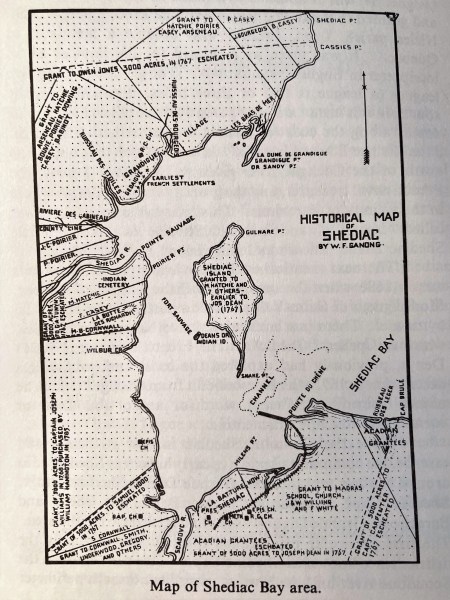

Large Lower left piece of land belonged to William Hanington 1785

William, however, was obviously made of sturdier stuff and delighted by what he found! A good size stream flowed into the bay and he had never seen such giant trees! He must have pictured the lucrative possibilities for trade in lumber, fish, furs and more.

Seven years after his arrival in Shediac, at the age of 33, he hired a couple of Indian guides to paddle a canoe over to Ile St. Jean (now known as Prince Edward Island) where there were other English settlers. The Darbys were Loyalist sympathizers who escaped from the rebels in New York. While riding along in an oxcart through St. Eleanor’s (now known as Summerside), he spotted a young lady (age 18) named Mary Darby, drawing water in her father’s yard. After a brief stay with her family, William and Mary married and paddled back to Shediac where they eventually raised a large family of 13 children.

After the first three years together, they persuaded Mary’s sister Elizabeth and her husband John Welling to come over from Ile St. Jean and settle on their land – becoming the second English family in Shediac.

And in the next five years, William boasted eight families on his property of about one hundred acres of cleared land. He opened a general store and dealt in fish, fur and lumber. The furs and timber were shipped to England and the fish to Halifax and the West Indies! He imported English goods from Halifax and West Indies products – mainly sugar, molasses and rum from St. Pierre. He also bartered with the friendly Indians for furs and helped them clear land.

Before long, a considerable village clustered about the Hanington Store – including a post office and a tavern. William remained the leading figure of the community and acted as the Collector of Customs of the Port, Supervisor of Roads and Magistrate enabling him to officiate over the marriages of many couples. To top it all off, in 1800, just 15 years after his arrival from England, this remarkable young man built a shipyard 10 miles north of Shediac in Cocagne.

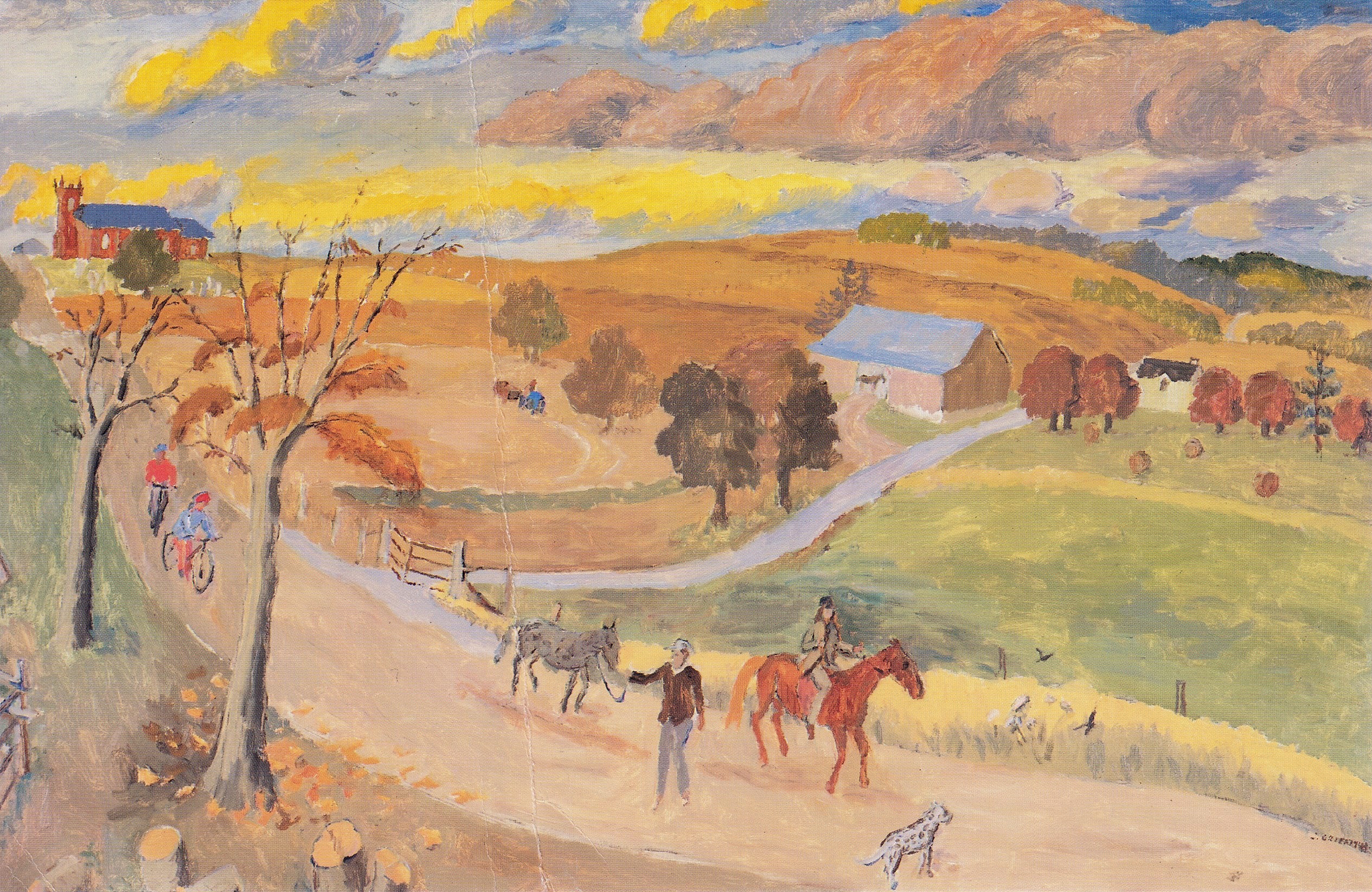

The only thing lacking in this delightful little community was a church. Until then, William being a religious man, conducted service in his home every Sunday and welcomed all to attend. Then in 1823, William donated the necessary land and lumber and oversaw the completion of St. Martin-in-the-Woods, the first Protestant church. He named it after his church in England; the famous St. Martin-in-the-Fields overlooking Trafalgar Square in London.

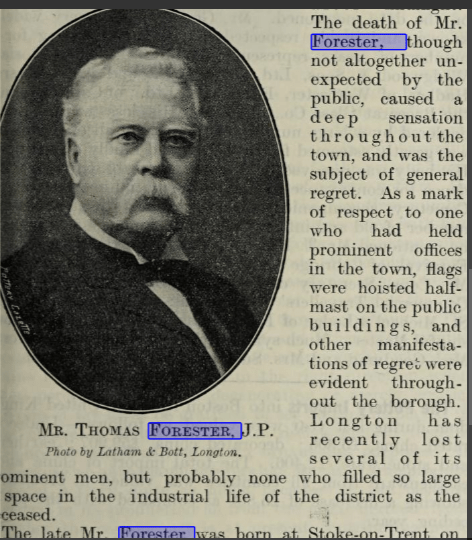

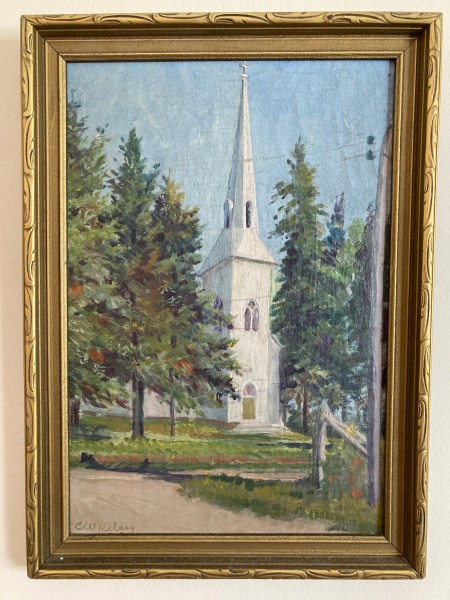

Painting of

St Martin-in-the-Woods Church

by Charles Kelsey

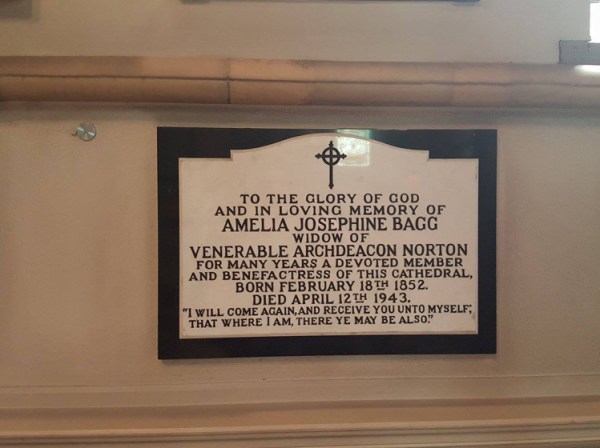

In 1934, my grandfather Canon Sydenham Lindsay (Shediac summer resident at Iona Cottage – She Owned A Cottage – with his wife Millicent Hanington and sometimes stand-in priest at the church) dedicated a large memorial stain glass window in the sanctuary to his father-in-law, Dr. James Peters Hanington (1846-1927) who was my great-grandfather and William’s grandson. The window was designed and installed by Charles W. Kelsey of Montreal and described as follows:

“The centre light of the window represents the Crucifixion, with Mary Magdalene at the foot of the cross, while the two side windows represent the Blessed Virgin Mary and Saint John the Evangelist.” (1934 – The Montreal Gazette)

Stain Glass Window in St Martin-in-the-Woods (photo credit Paul Almond)

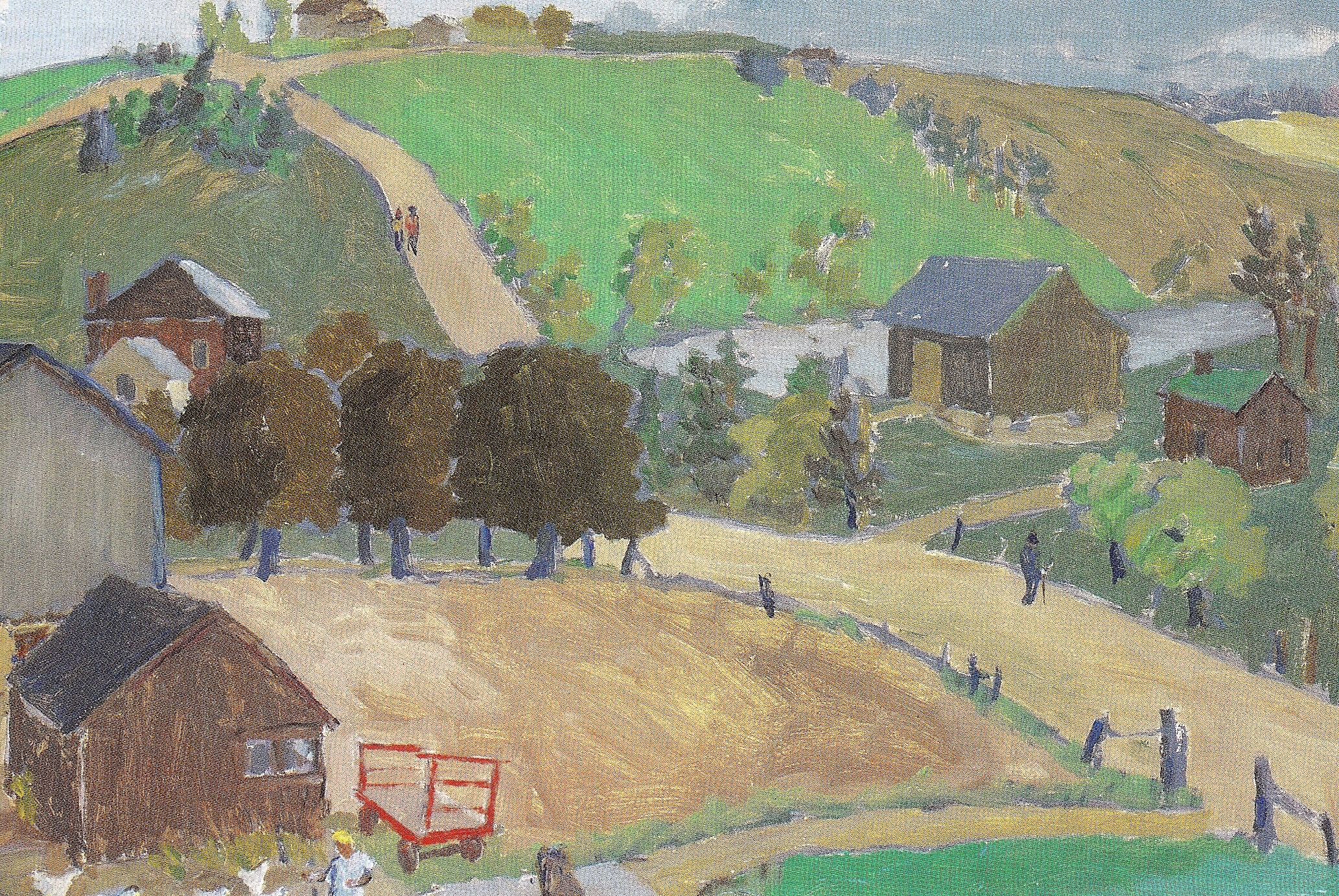

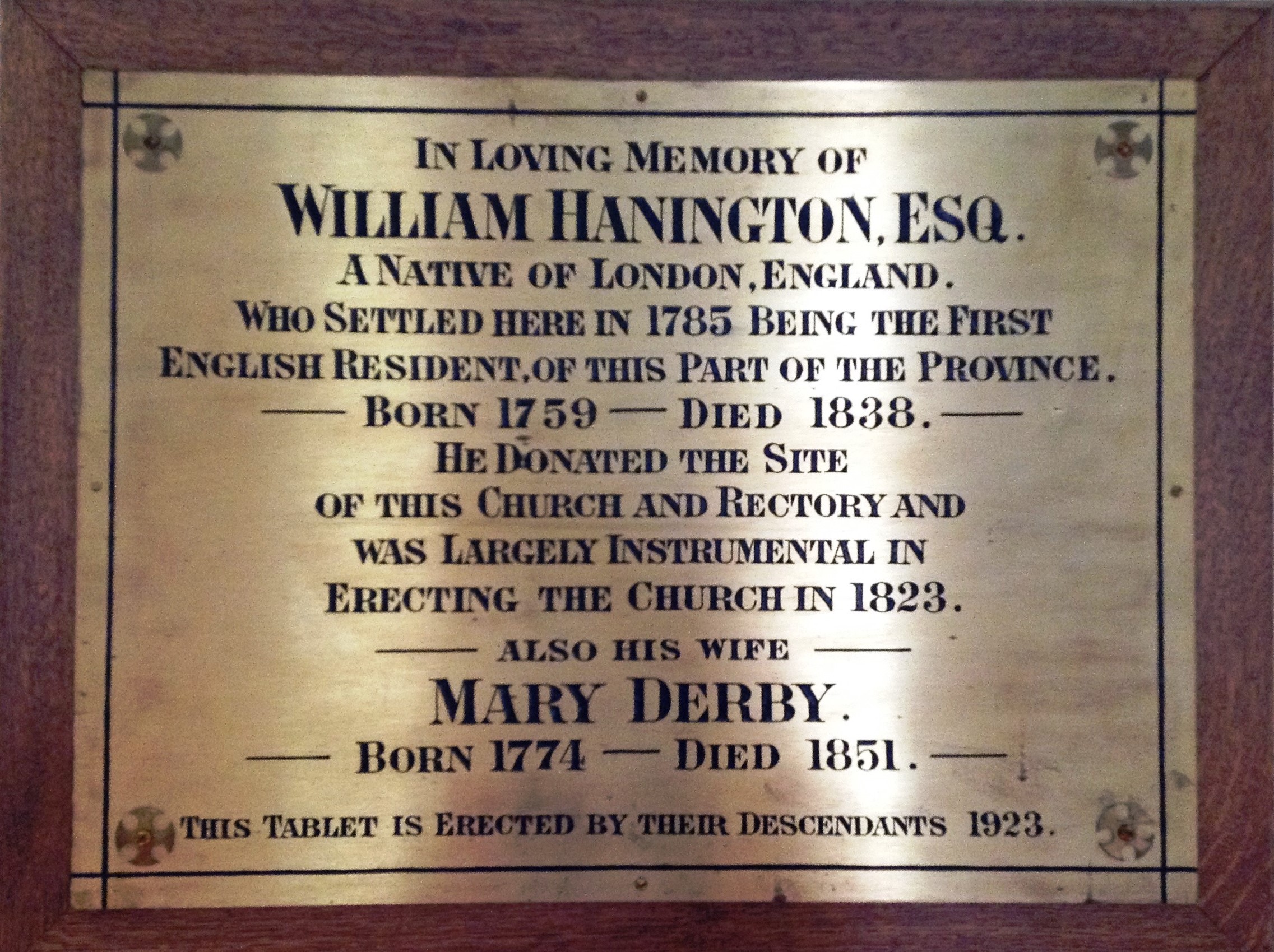

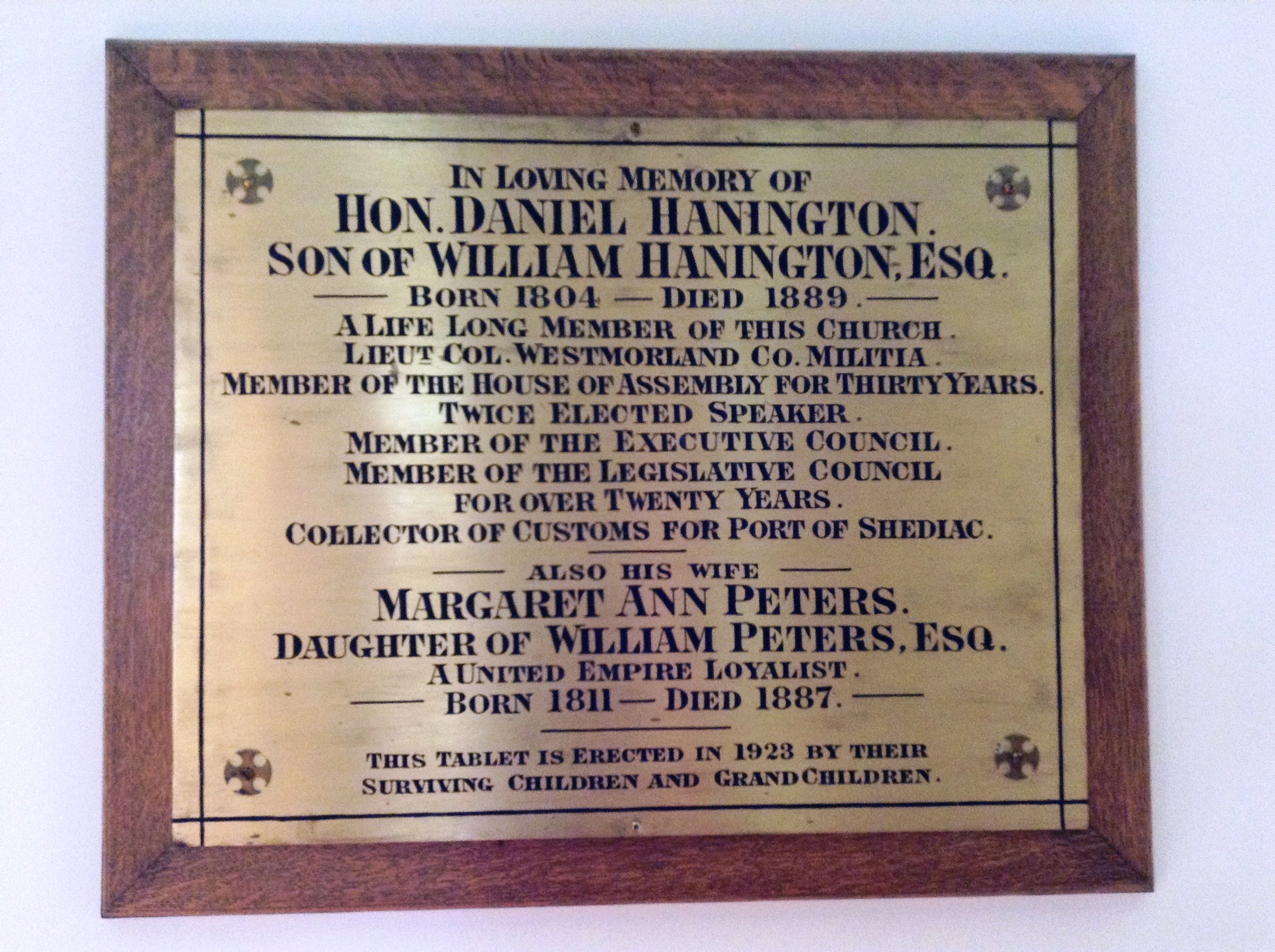

Also mounted inside on the church’s side walls are two honourary brass plaques. One in memory of William and his wife and one in memory of his son Hon. Daniel Hanington (1804-1889) and his wife Margaret Ann Peters – my great great grandparents.

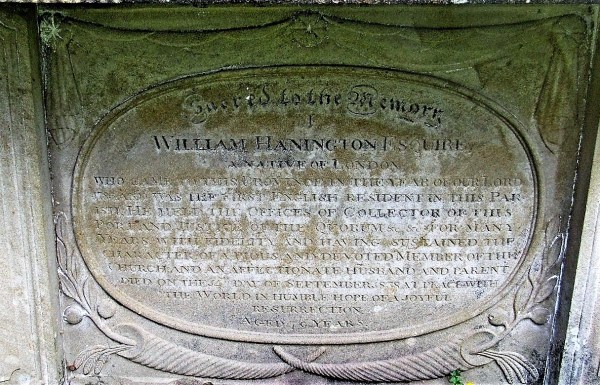

William died in 1838 at age 79. A huge memorial of native freestone marked his grave, in the cemetery beside his beloved church nestled in the community of Shediac, where he spent a lifetime building a “commodious estate” from a forest of giant trees.

Two hundred years later on this anniversary of the St. Martin-in-the-Woods church, William and Mary are lovingly encircled by the graves of several generations of their descendants.

*********************************************************************

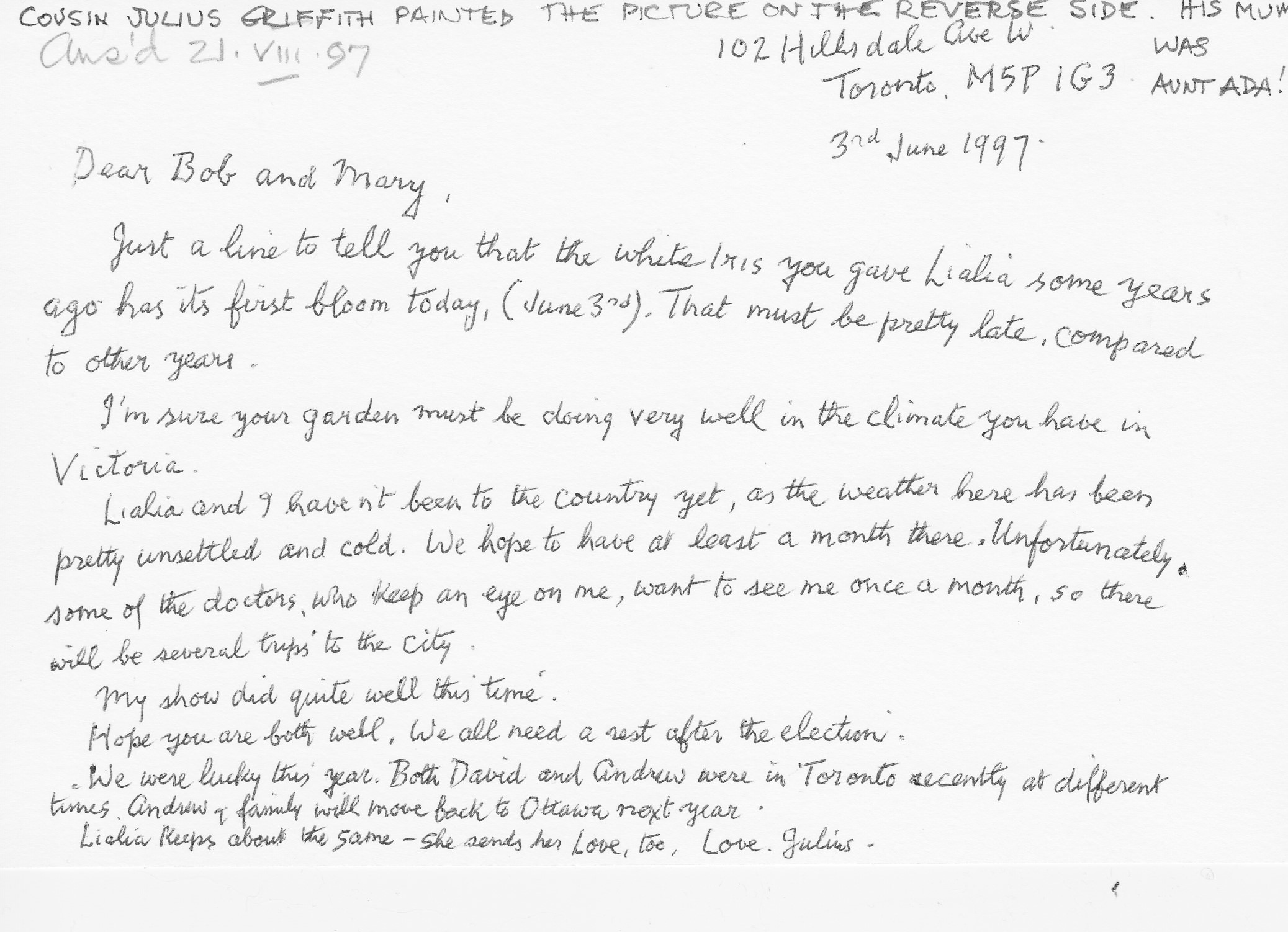

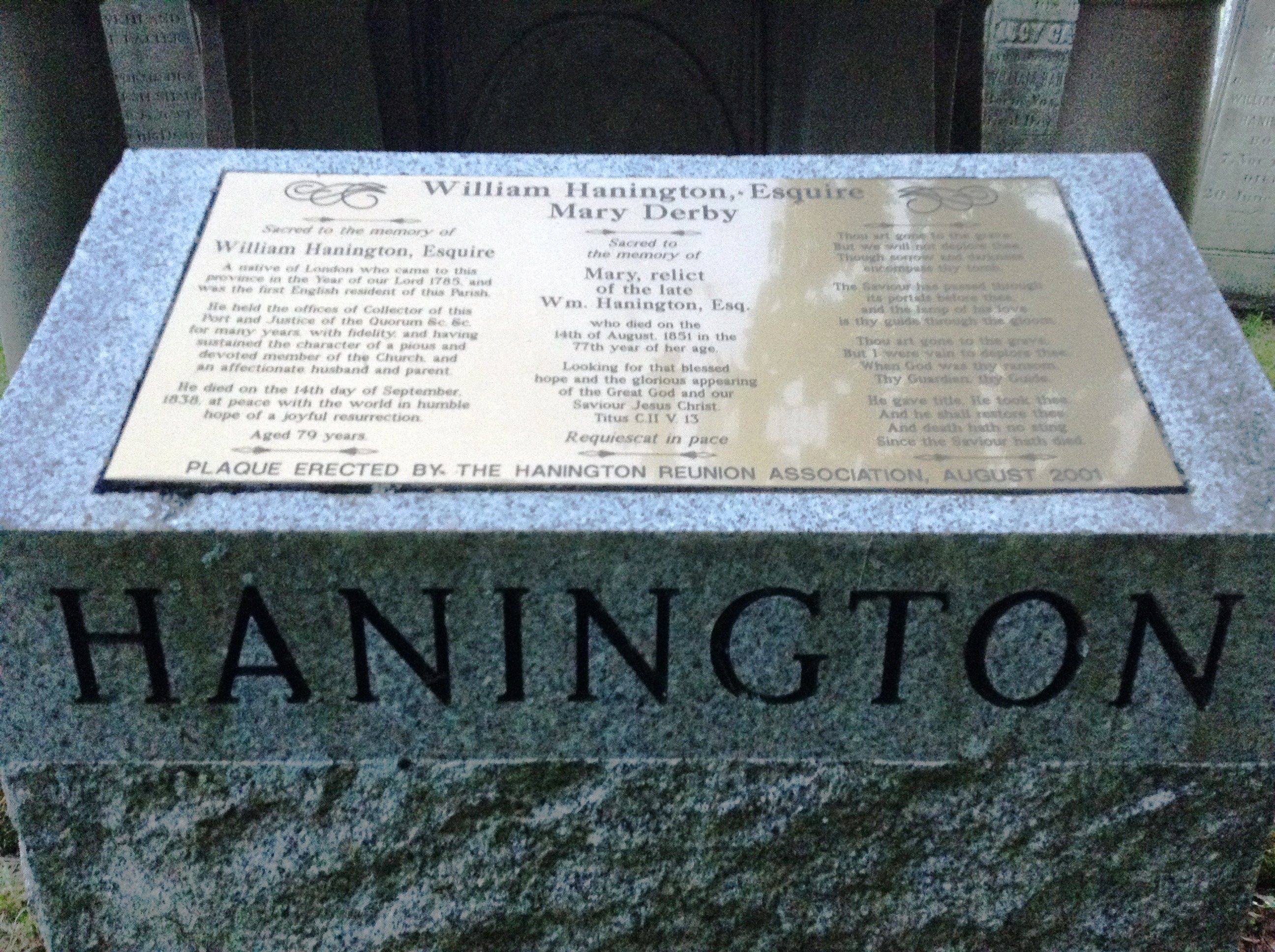

A memorial plaque to William and his wife Mary, was erected in 2001 by the Hanington Reunion Association. This year the Association will be adding a bench in the cemetery in celebration of the 200 years.

Close-up of the Headstone of William Hanington (1759-1838)

(L)Hanington Reunion Association Plaque (2001) honouring William Hanington and his wife Mary Darby and (R) photo by Scotty Horsman showing William’s large headstone at the side of the church.

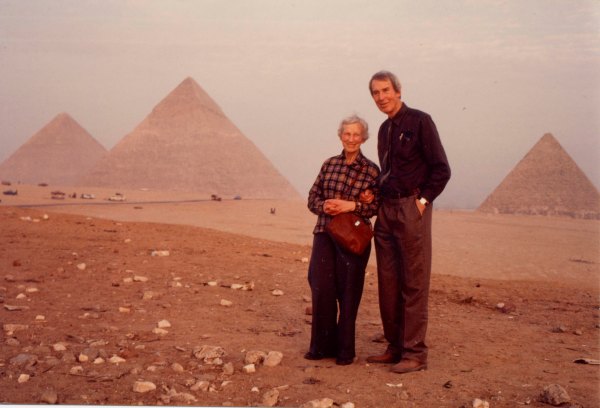

In 2015, my sister and I visited the church and our ancestors in the graveyard and also enjoyed meeting some Hanington cousins as well!

Read our story here: Sister Pilgrimage

***********************************************************************

ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATION DETAILS FOR SEPT 16-17, 2023:

The main events for the 200th Anniversary will be Sept. 16th and 17th with a corn boil, hotdog/hamburger barbecue and cake on Saturday, Sept. 16th. There will also be games, a bonfire, fireworks and music at the church shore.

The Anglican Bishop, David Edwards, of Fredericton will be attending this celebration. He will also be at the 10:30 AM church service on Sunday, Sept. 17th. After the church service there will be a pot luck lunch and a skit in the hall. There will also be items on display in thechurch basement and in the hall. There will be items for sale – glasses, mugs and lapel pins, with the Hanington crest as well as lapel pins. ornaments and trivets with the church on them.

**************************************************************************

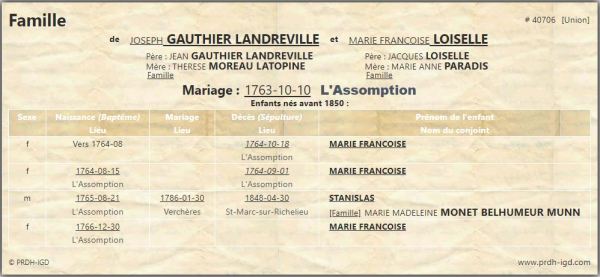

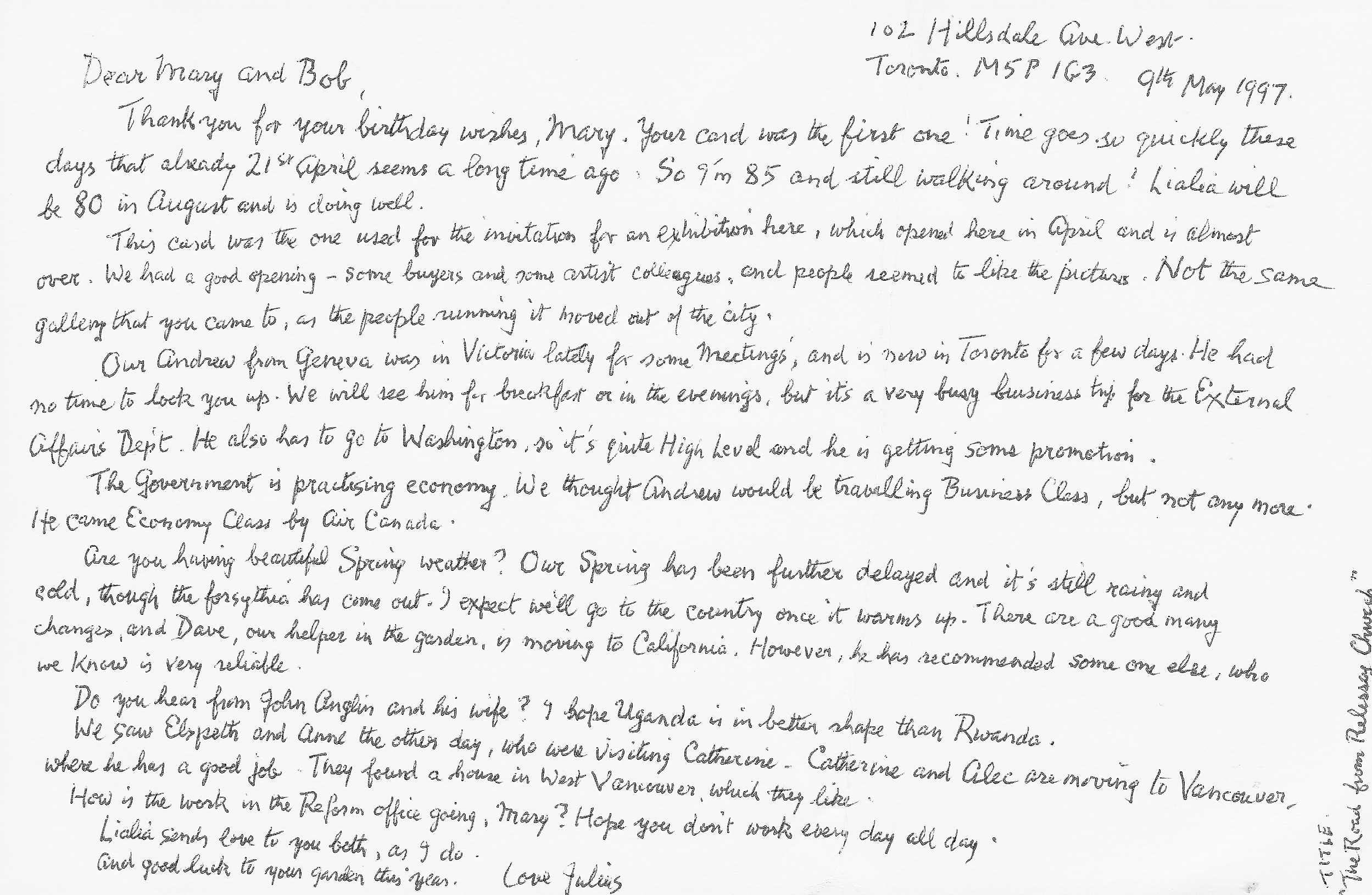

If anyone would like a PDF copy of Lilian Hamilton’s famous Hanington genealogy family tree book from 1988, please email me at anglinlucy@gmail.com

My cousin was kind enough to take the time to copy the book into PDF so that everyone can have a digital copy.

My Hanington number is 6-9-7-3-4 if anyone wants to know who I am!