With additional research from Justin Bur

Huntly Ward Davis (1875-1952) was a Montreal architect who designed elegant downtown homes, banks and institutional buildings in the first half of the 20th century. Some of those buildings still stand today, others have disappeared. Many of Montreal’s heritage buildings, built when the city was Canada’s most important business and banking center, have been demolished and replaced by high-rise office towers and apartment buildings. As a result, Davis has been largely forgotten by the public, but his descendants – my cousins – are proud of his architectural legacy.

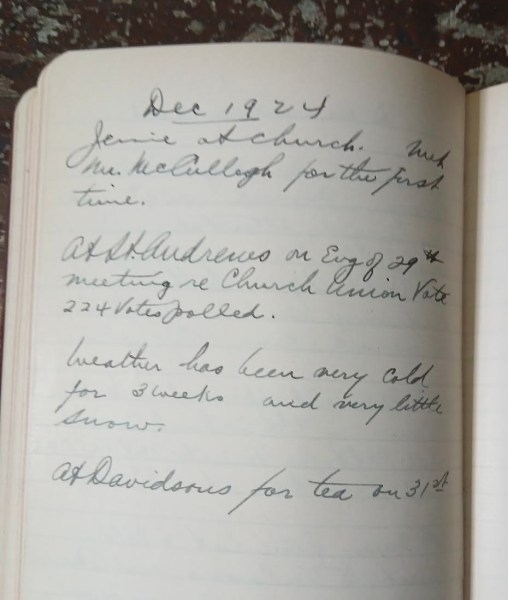

Huntly was born in Montreal on October 22, 1875, the oldest son of Moses Davis (c. 1847-1909), head of a customs brokerage firm, and Lucy Elizabeth Ward (1850-1924). Moses was originally from St. Andrews, Quebec, a village on the Ottawa River between Ottawa and Montreal.1

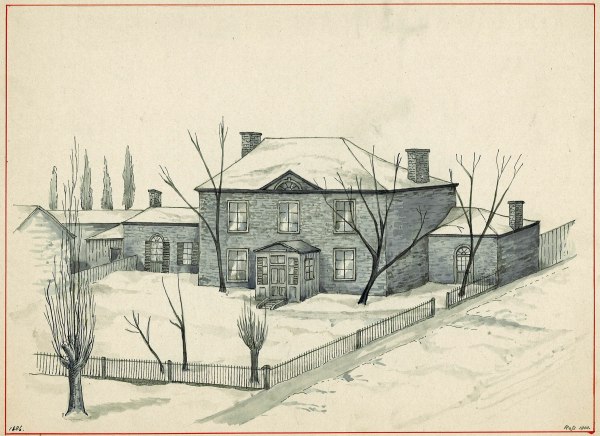

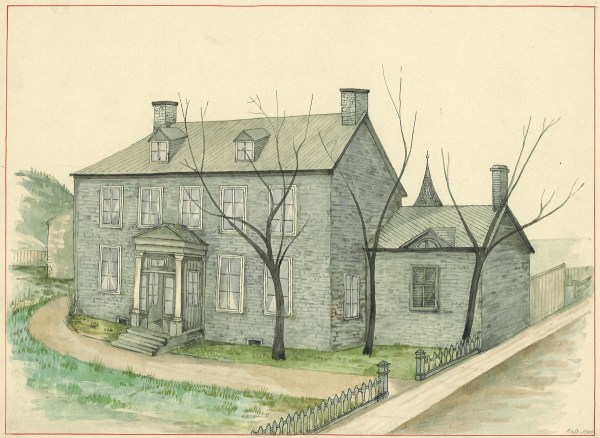

His mother’s father was well known in business and in politics. James Kewley Ward (1819-1910), was born on the Isle of Man, located in the Irish Sea. James immigrated to New York State in 1842 and married his first wife, Elizabeth King, there. The family moved to Lower Canada in the early 1850s and James bought a lumber mill on the Maskinongé River, northeast of Montreal.

Elizabeth died when daughter Lucy was four years old. James remarried and he and his second wife, Lydia Trenholm, had a large family. Lucy’s granddaughter later recalled how warm and compassionate Lucy was, so perhaps she grew up helping her younger siblings.

In the 1870s, the Ward family moved to Montreal, where James opened a sawmill on the Lachine Canal and expanded his business interests to cotton. A Liberal in politics, he served as mayor of the village of Côte St. Antoine (now the City of Westmount) from 1875 to 1884, and in 1888 he was appointed to the Legislative Council of Quebec. He was known for his generosity to charities.2

Moses Davis and Lucy Ward were married in Montreal in 1874, and Huntly, the eldest of their three sons, was born the following year. Huntly attended school in Montreal, then studied architecture in Boston, graduating from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1898. He returned to Montreal and eventually went into partnership with architect Morley Hogle. After Hogle’s sudden death in 1920, Huntly worked on his own.3 He was a member of the Quebec Association of Architects and of the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada.

Huntly married Evelyn St. Clair Stanley Bagg (1883-1970), eldest daughter of Robert Stanley Bagg and his wife Clara Smithers, on Oct. 26, 1910, at Montreal’s Anglican Church of St. James the Apostle. The following day, The Gazette’s society reporter called the event “one of the prettiest of the season’s fashionable weddings” and described the bride’s ivory satin gown, embroidered with seed pearls.4

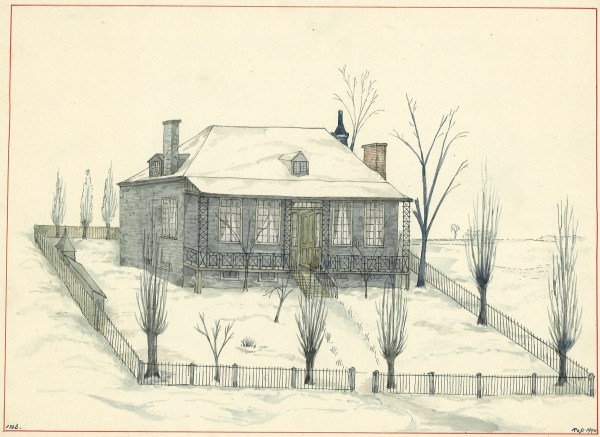

Huntly and Evelyn lived in an apartment building that Huntly had designed on Summerhill Avenue, a short street off Côte des Neiges Road, just up the hill from the house where Evelyn had grown up. Evelyn lived on Summerhill for the rest of her life and the couple’s granddaughter still remembers the spacious eight-room apartment and the furniture Huntly had designed.

Huntly and Evelyn also had a country house at Ste. Marguerite, in the Laurentian mountains north of the city. That was where Huntly died, suddenly, on October 12, 1952, at age 76.5 His name is on a plaque in the Bagg family mausoleum at Mount Royal Cemetery.

Huntly and Evelyn had one daughter, Clare Ward Davis (1911-2007). As an adult, she often repeated expressions she had learned from him as a child that reflected his simple sense of justice: “never assume”; “I divide, you choose”; and “a nectarine is a plum’s mistake”.

This down-to-earth approach to life was alsoreflected in the buildings he designed. Son-in-law Norton Fellowes, who was also a Montreal architect, prepared an obituary of Huntly, focusing on his professional activities and published in the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada Journal.

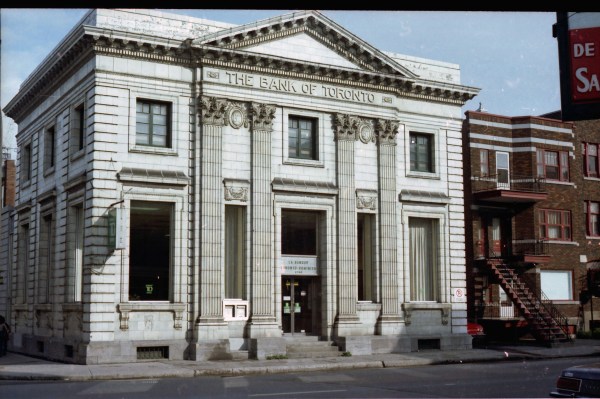

Norton wrote, “In the early years of the 20th century, Mr. Davis was a ‘contemporary architect’ for during this era of post-Victorian vulgarity, he allied himself with that small group of young architects who saw beyond the ornate fashion of the day and consistently designed quiet, dignified town houses, country homes, banks and institutes of learning, always in the tradition of fine craftsmanship and classical proportion. The Greenshield and Townsend country houses still grace the bays of Lake Manitou in the Laurentians and the main building of the Children’s Memorial Hospital, the Trafalgar Institute, the Walter Molson residence on McGregor Street, and the head office of the Bank of Toronto in Montreal are all still permanent monuments to a man who followed the highest traditions of the profession.

“During the last few years, although well beyond the age when others retire, Mr. Davis, at the age of 75, was still young enough to understand the trend to more functional design and it was not surprising that in 1952, he designed and supervised the building of several small, efficient new branches for the Bank of Toronto in the Montreal area. Mr. Davis thus worked with dignity and courage for a full half century as a member of the architectural profession.”6

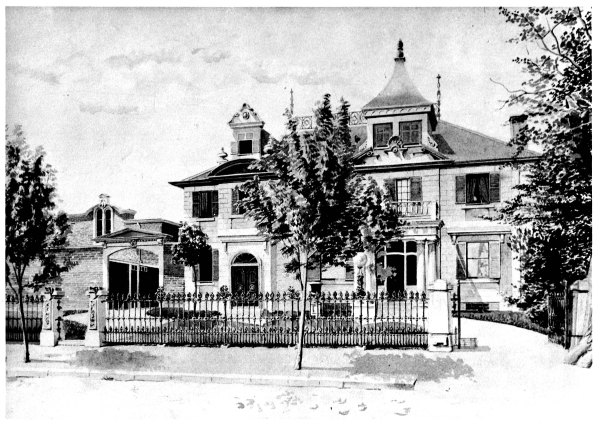

Neither is it surprising that he designed at least one building for his wife’s family. The Bagg family had extensive properties in Montreal, mostly in the Mile End area, just east of Mount Royal, but they also owned a few properties downtown. In 1926, Huntly designed a brown brick apartment block on Ste-Catherine Street West, near Guy, for the Stanley Bagg Corp. It was three stories, with small shops on the ground floor.

He may have been involved with another project on land that belonged to the Baggs, a commercial building at the southwest corner of Ste-Catherine Street and Peel. It was built in 1911, shortly after Huntly and Evelyn were married, however, no architect’s name was mentioned in any newspaper reports or in the building’s lease. All building permits were destroyed in a 1922 fire at city hall.

The gleaming, white vitrified terracotta façade (a treatment popular between 1910 and 1915) of the H&M clothing store still stands out at this busy intersection in the heart of downtown. Thousands of people pass by it every day. Although his name was never officially associated with it, this may be the most familiar building Huntly designed.

Notes

Some sources, including the Biographical Dictionary of Architects of Canada, spell his name Huntley, however, his baptism record and a letter written by his mother spell it Huntly. I have used his mother’s spelling. Most architectural references say H.W. Davis.

The lot on Ste-Catherine just west of Guy (St. Antoine Ward, lot 1679, minus a strip of land previously detached for a laneway,) was purchased by the Estate of the late Stanley Clark Bagg in 1885, probably as a rent-generating property. At the time, a three-story brick building and several other buildings were on the lot. The property passed to the Stanley Bagg Corp. when it was founded in 1919. The current building, designed by Huntly Ward Davis, was constructed in 1926. The property was sold in 1957.

The property at Ste-Catherine and Peel (Saint-Antoine Ward, lot 1477) was purchased by the Bagg Estate in 1879. At the time there were three, three-storey stone-front brick houses on the lot. In 1886, these buildings were converted to shops with flats above. They were demolished in 1911 and construction began on the current building, at a cost of $60,000. The Stanley Bagg Corp. sold the property in 1951.

Sources

- “Mr. Moses Davis Died Suddenly Last Night”, The Montreal Star, April 17, 1907, p. 6. Newspapers.com, accessed Oct. 28, 2025.

- Leslie Quilliam and Victor Neale, “James Kewley Ward”, Kelly Dollin, editor, New Manx Worthies, Manx Heritage Foundation/Culture Vannin, 2006, iMuseum, https://imuseum.im/search/collections/people/mnh-agent-94625.html, accessed Oct. 27, 2025.

- “Huntley Ward Davis”, Biographical Dictionary of Architects in Canada, 1800-1950, Robert G. Hill, editor, http://dictionaryofarchitectsincanada.org/node/825, accessed Oct. 27, 2025.

- Social and Personal, The Gazette, Oct. 27, 1910, p. 2. Newspapers.com, accessed Oct. 27, 2025.

- Huntly Ward Davis, Obituary, The Gazette, Oct. 15, 1952, p. 14, Newspapers.com, accessed Oct. 27, 2025.

- Norton A. Fellowes, “The Late Huntley Ward Davis, Montreal Architect,” Royal Architectural Institute of Canada, Nov. 13, 1952

This article also appears on my family history blog http://www.writinguptheancestors.ca