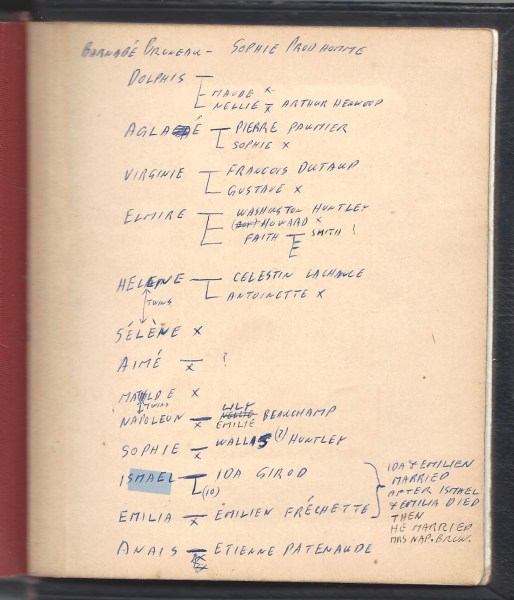

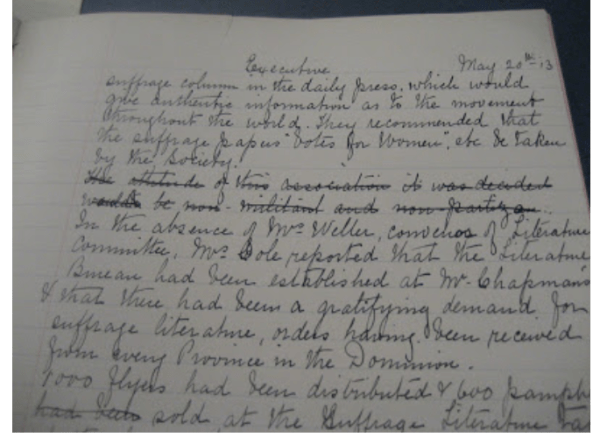

Chapter 2 of Diary of a Confirmed Spinster a story based on family letters from the 1900 era from Montreal and Richmond, Quebec. The story in pdf form is archived online at National Library of Canada. (See below)

But, first, let’s go back to the beginning. (But which beginning? The beginning beginning. The I AM BORN beginning, to once again invoke David Copperfield, that despite appearances is not my favourite novel. Middlemarch is.)

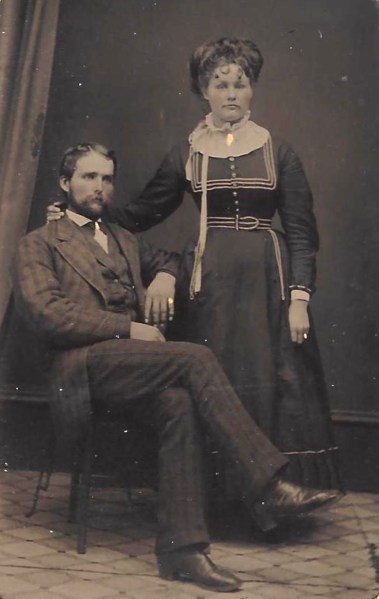

Easy enough. I am born in January 1884 in a green clapboard rental house in Melbourne, Quebec, 10 months after my parents’ marriage.

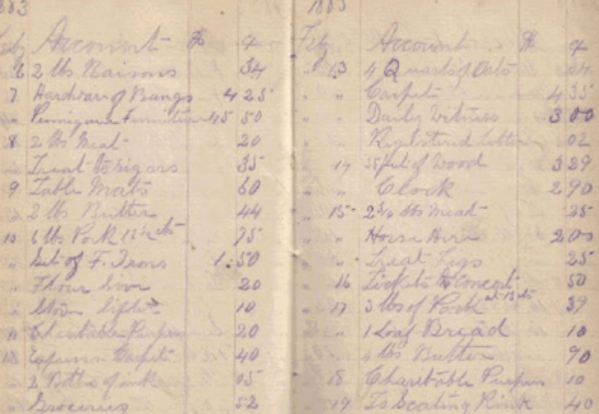

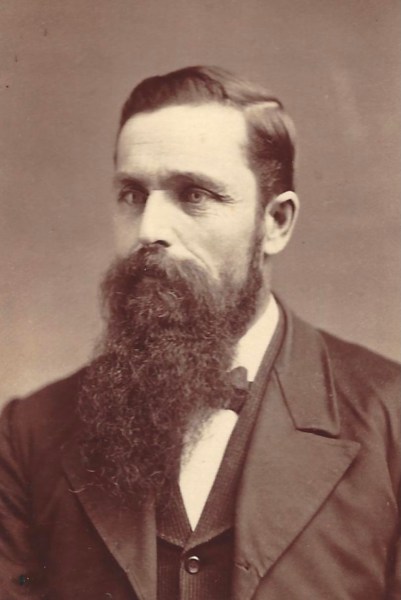

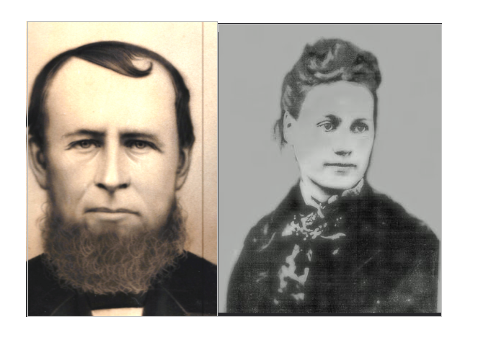

I know this because I have been told and also because the proof resides in shaky ink strokes in my father’s Store Book for 1884.

His household accounts that he kept from 1882, before his marriage to 1921, the year he passed away.

Fifty years of family accounts, kept in little black books.

It could be claimed that the entire story of our family is told in these pocket-size volumes, the practical side at least. The down-to-earth work-a-day side.

I was born in early January 1884 because the store book has an entry on the 7th, inserting baby’s birth 25 cents. I have survived my first challenge.

Under that breast pump 75 cents. Breast shield 25 cents. Along with one quart of milk 5 cents, a loaf of bread 10 cents, a gallon of coal oil, 25 cents. Two cords of wood 8 dollars and 35 cents. 11 pounds of oatmeal 38 cents. One dozen herring 20 cents. 1 ½ pounds of steak 15 cents. And rent 25 dollars a month. The staples of bodily existence then and today: shelter, heat, light and daily bread.

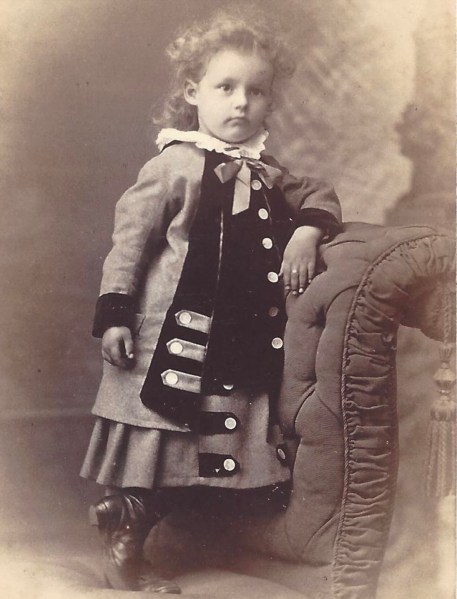

On February 19th a baby cradle is purchased 3 dollars. And some flannel and some cotton for baby. And on April 28, baby’s picture 25 cents. I have officially arrived. I have survived the precarious early days. I am safe to be sketched in silver bromide.

On June 27, 1 baby carriage 6.37. October 1884, one crib. 2.75. Some wool for baby 2.60.

A year later, baby’s first shoes, 1.20. I am now officially a financial burden on my parents. They would spend a great deal on shoes and boots – and the mending of same – for me and my three siblings in the following decades.

In June 1886, a child’s broom is purchased. 15 cents and I begin to pay for my keep. In those days they began teaching girls the womanly arts very early.

Also purchased that month: baby’s first book. We are Scots after all, who value education above all else. “An education is something they cannot take away from you,” my mother always says.

Still, it’s something of a mixed message I am being sent, as a 2 and ½ year old. But I might as well get used to it. Being a female, I will be showered with mixed messages for most of my life.

Then, the narrative in numbers continues: 1890 to 1895 school fees 25 cents a month. The occasional slate 5 cents. Bottles and bottles of cough medicine 25 cents each. (Cough medicine had kick in those days.) Later scribblers 5 -7 cents. Skating rink 10 cents. Soda at Sutherland’s drugstore 5 cents. (Soda had kick in those days, too.)

Also pocket money for Edith 5 cents. I guess I was doing a lot more than sweeping by then. Oddly, my younger brother Herb received ‘wages’ for his household chores.

And then I grow up. St. Francis Academy 50 cents a month. Latin text 1.25. Euclid’s geometry 1.00, the Jamaica Catechism, 80 cents, etc.(Students must purchase their textbooks, many published by the Renouf Company of Montreal, who, in turn, cash city teachers’ paycheques for them, as women don’t have bank accounts.) And I get stockings and gloves at Christmas, just like Mother.

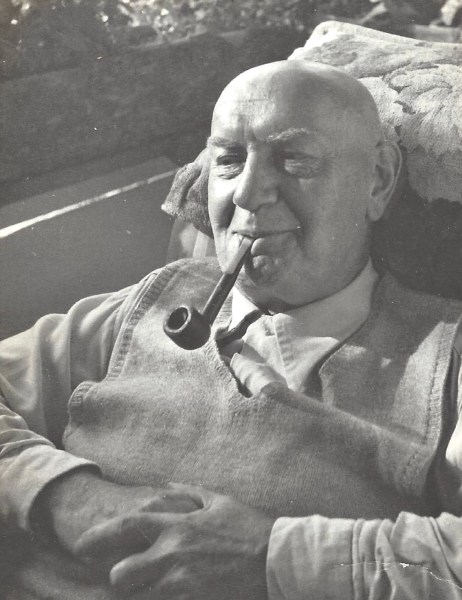

We are living in our own house by 1896, built at a cost of 2,718 dollars, not including landscaping. My father is by now a well-to-do hemlock bark dealer. Hemlock is plentiful in the E.T. and used in the leather tanning process. Father sells his bark to tanneries in Montreal, New Hampshire and Maine.

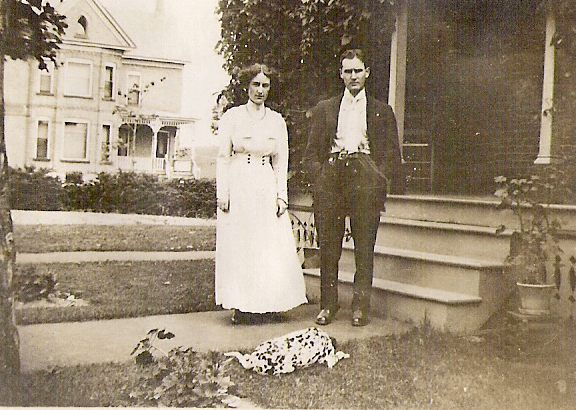

The mortgage on our house is 30 dollars a month, similar to what we paid on the rental house, but “Tighsolas” or House of Light in Gaelic is ours. And it is a fine house, a brick-encased Queen-Anne Revival in the good part of Richmond, not far from St. Francis Academy on College Street. (The kind of house seen often in Ontario but fairly rare in Quebec.) Building this house my father inspected every plank, brick and tile himself, tossing aside more than he used.

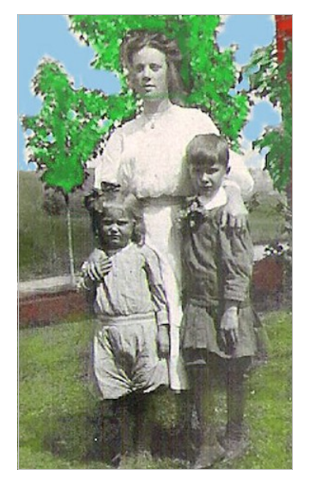

By now, as I said, I have three siblings, a younger brother, Herb and two younger sisters, Marion and Flora, born 1885, 1887, and 1892.

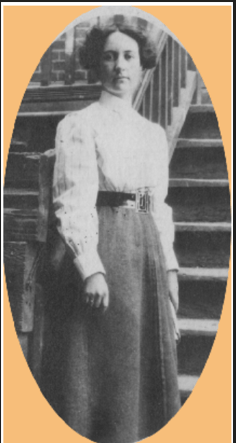

By 1901 I am ‘fully out’ : corset for Edith 2.35. I start wearing my hair tied up around then, but only at dances. Combs for Edith: 20 cents.

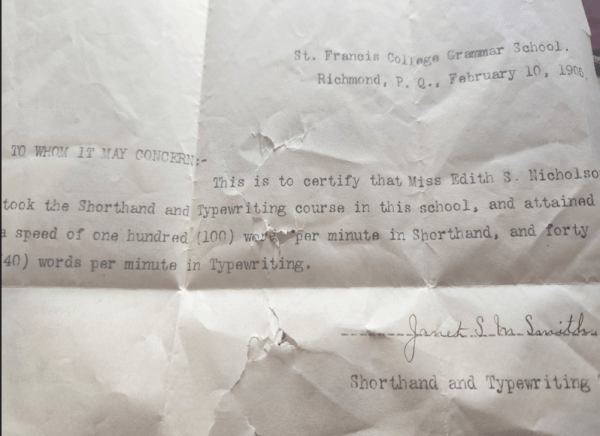

I graduate from St. Francis Academy II in 1903 and a little later take a stenography course there. Stenography is an up-and-coming profession for women. 13.50 for the course. 1.28 for a shorthand book. 5 cents for a reporter’s notebook.

I pass the course with 100 words a minute in shorthand and 45 words a minute in typing, good enough to get a job, but my parents don’t want me going to the city to work. Life in the city for young working women is a dreary business, at least according to a cousin, Jessie Beacon, in a letter to Mother.

Jessie laments that she works until six at her insurance office, goes home to her boarding house for a “lousy hash complete with garnish of housefly” and then dresses for a predictably boring evening.

My parents are intent on saving me from such a degrading existence and seek a job for me in Richmond, but jobs for young people in country towns are few and far between.

Money is plentiful at home despite the fact my father has had to change lines of work. He now sells pulpwood instead of the bark. At Christmas, over and above the usual stockings and gloves, there are gifts of watches, rings and perfume.

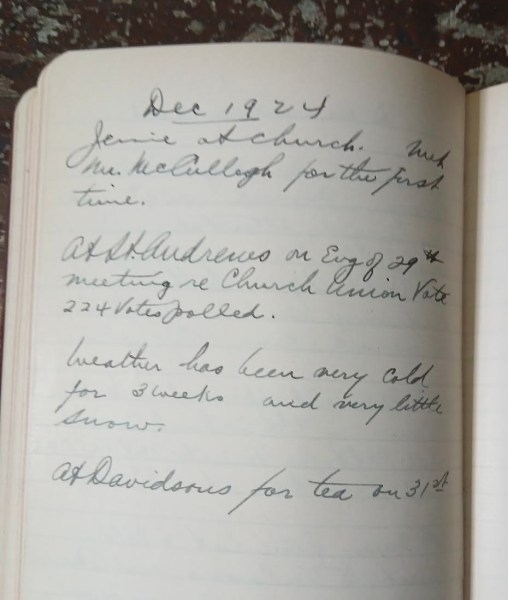

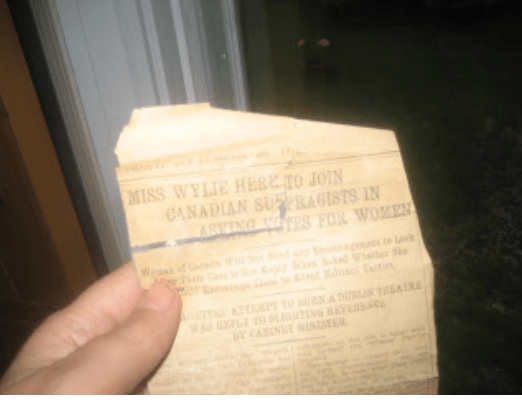

In 1905 my younger sister, Marion, leaves for McGill Normal School and adventures in the Big City. My determined little sister has managed to convince my wary parents that the City is safe, as long as she rooms at the YWCA on Dorchester.

And, as Herb works in Montreal, at the E.T. Bank, she is not alone, so my parents permit her to go despite the great cost: 16.50 a month.

Everything in life is timing!

And I am left alone at home with my little sister, born nine years after me. My parents shower me with ‘pity gifts’ at Easter: 5.00 for a plaid “Montreal” dress. (Plaid voile is all the rage this year, I read it in the Delineator.) 2.35 for a ticket to see the Madame Albani concert in Sherbrooke. Opera singer Emma Lajeunesse, now in her middle age, is a ‘local’ girl from Chambly made good. She is world-famous, a long-time favourite at London’s Covent Garden. So, this is a huge event. All of the. E. T. seems to want to attend.

At 22, I feel like a debutante about to make her grand appearance under the patronage of a local legend. But nothing comes of it. No eligible young men come out to the home-coming concert.

But late 1906 the pulp contracts dry up. To add fuel to this fire, we are disinherited by a wealthy Maiden Aunt on her deathbed.

My brother takes this especially hard.

“Well, now that my house is being given to someone else, I will have to give up all hope of being rich and look at it as a fortune lost,” he writes in a letter home.

“My house? MY house?” exclaims Marion at Christmas. She is now working at Sherbrooke High School and boarding at a Mrs. Wyatt’s who has a daughter, Ruth, Marion’s age. “What has Father been telling him?”

I don’t tell my sister that Herb believes we were disinherited because Old Aunt Maggie did not approve of ‘working women.’

In June 1907 my father is desperate for work with a meagre 33 dollars left in his bank account. He applies to our local Member of Parliament, E.W. Tobin, to work as inspector on the crew building the Canadian Transcontinental Railway.

He receives a polite letter from their offices in Ottawa. They say they have their full complement of inspectors. They acknowledge that Tobin has been in to see them on his behalf.

Then in August a great bridge, half built, collapses, the Quebec Bridge. It was to be the world’s longest suspension bridge. 78 men die, mostly Mohawks from Cawgnawaga near Montreal.

The bridge was a component of the CTR. Magically, there is a need for inspectors at end of steel and father gets the call to La Tuque, to be Timber Inspector at 100 dollars a month.

My parents take out a 1,000 dollar insurance policy on my father’s life. It is well known that jobs on the railway are dangerous.

My mother exchanges one worry for another.

“What is a timber inspector? Is it safe? It doesn’t sound safe.”

And I am still at home, no income, no prospects.

Then arrives a letter from Reverend J. R. McLeod, my mother’s cousin living in a town half way between Montreal and Quebec City.

Three Rivers, Sept. 1907

My dear Friend,

I have but a few minutes to write as prayer meeting is starting. I was asked yesterday by the Manager of Works in a village 15 miles from here if I could find a suitable girl to teach a small school, about 10 children. My thoughts went to you. They will take you without a diploma. They offer $20.00 a month. I know you are fit for the position.

Regards, Reverend J. R. Macleod

“Should I accept now, I mean that Father is away?” I ask my mother.

“It is your decision to make,” my mother replies. She does not seem surprised at all by the letter from her cousin.

Mother hands me another letter, just arrived in the mail, from a young friend of the family’s, Mary Carlyle. The correspondent omits the obligatory opening pleasantries and gets straight to the irksome point:

“Dear Maggie,

I am writing you with such good news. I am to be married! He is a George White and he is from Kingsey. He is a sweet, kind man, with a good position and very good looking, in my opinion. It is such a relief. I was worried I was destined to be a burden on Father.”

“Kingsey. So, that’s where all the perfect men are,” I say to Mother in a tired voice but my mind is suddenly made up. I climb the stairs to my room to scratch off a note to J.R. McLeod saying I will take the job as offered.

END

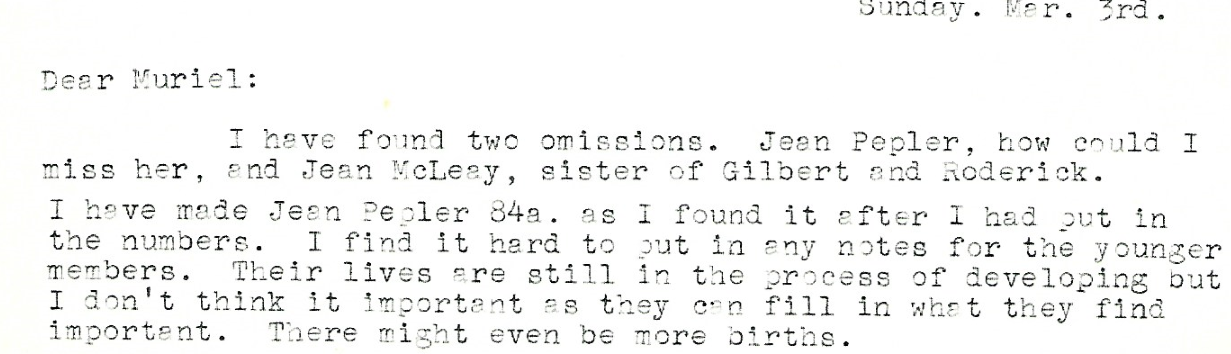

(This is Chapter 2 of a novellette I wrote, Diary of a Confirmed Spinster, part of School Marms and Suffragettes that can be found at the National Archives of Canada. The story is based on the letters and other memorabilia of the Nicholson family of Richmond, Quebec).

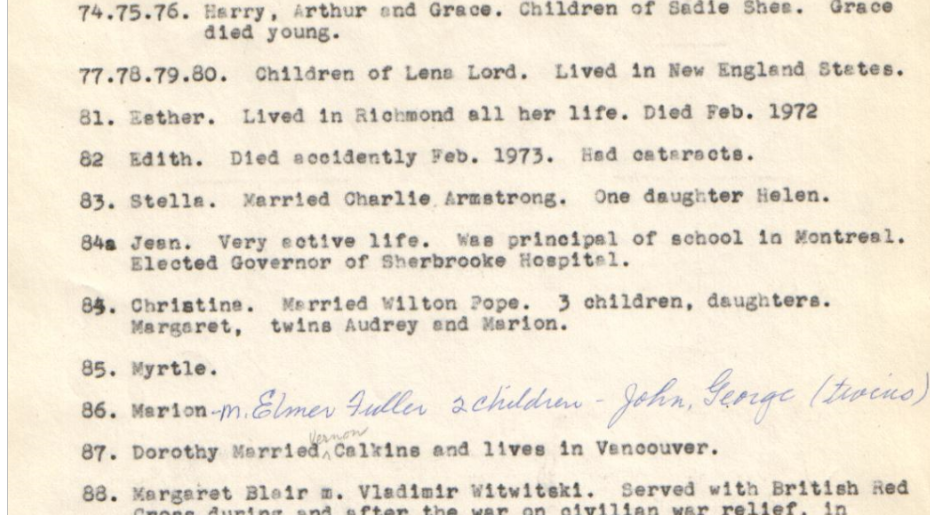

At National Library of Canada. Online collection.