……..of Morin Heights Quebec now of Dollard-des-Ormeaux, is 93 years old.

I have known her for about three years. We talk for an hour every day about her young life and all sorts of interesting subjects. I find her quite open minded with regard to religion, the latest news on the radio, world affairs and articles I download and read to her, as her eyesight is failing.

Ruby was born in Morin Flats, as it was called until 1911, when the name was changed to Morin Heights.[1] There were 5 children in the family, one boy and four girls.

Her great-grandparents were pioneers who came to the area from Ireland in the 1800’s possibly due to the potato famine. Her parents met and married and worked a cattle and dairy farm first in the 1890’s in Leopold, Quebec, but when family started to arrive they moved to Morin Heights so the children could be educated, and they ran the family farm, called ‘The Red and White Farm’ where Ruby was born.

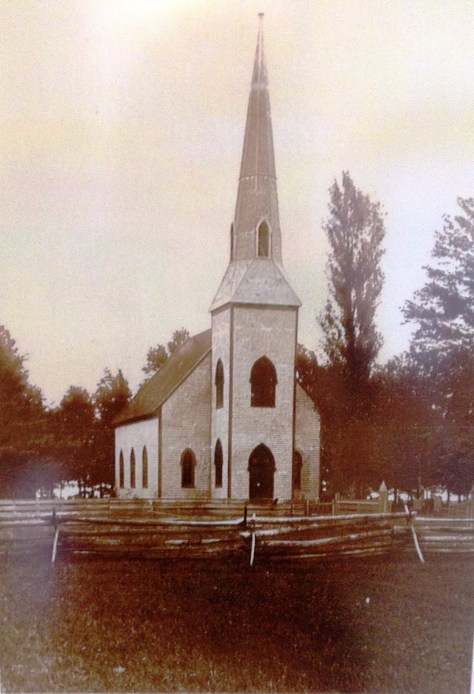

The first settler in Morin was Thomas Seale, from Connaught, Ireland, who had started clearing his farm at Echo Lake in 1848. Families that had originated as pioneers in Gore, Mille Isles and other townships settled Morin along with emigrants directly from Ireland.[2]

The first Census in the area was the 1861 Census of Morin Flats, County of Argenteuil, Quebec, Canada and many of the 470 people named on it when I read them out to her, were familiar to Ruby either as family, friends, or neighbours’ names.[3] So it would seem the residents of Morin Heights tend to stay put!

Ruby’s family farm had four Jersey milk cows, one Holstein, which she tells me gave ‘blue milk’ which was fat free milk, one Ayrshire and 2 Clydesdale horses and some chickens. The family farmed hay, oats, corn and buckwheat. The River Simon ran through their property and Ruby often fished for perch and bass, and her mother cooked them for the evening meals. Ruby told me that they had a small spring next to the river from which her father piped water, into the barn and the house, and that the water was ‘fresh, cold, and the best water around’

In the winter, Ruby had to shovel snow, help in the kitchen and anything else that needed to be done. As she told me ‘We were never bored, we had no time to be bored’

In April, all the family spent a week in the fields, with the ‘stone boat’ a large piece of wood, with ropes at each end. All in a row, and bending down the family cleared the whole field of stones and debris, putting them on the ‘stone boat’ and either pulling it as they went or hitching up one of the horses.

The stones would then be piled in a corner of the field, often higher than the children and then Father could plough and sow the fields.

At 4am every day, her Father would rise, curry and comb the horses, clean and feed the animals put wood in the wood burning stove and boil the kettle. By that time Mother was up and the family day began. In summer and spring, Father would milk the cows then put the milk into the metal churns, take it to the road running outside the property and leave it for pickup. Once a week, they received a cheque.

Some milk would be kept back for Mother to make her butter, to sell in the village for extra income. It was Ruby’s job to churn the wooden churner, with the family dog standing very close by, waiting for the butter milk he knew he would get at the end of the churning. Her mothers’ dairy was scoured daily and kept spotless. After the butter was churned and firm, which could take up to three hours or longer, her mother would take the two large wooden paddles and shape the butter into one pound blocks. Then they were wrapped in parchment paper for the trip to the village to sell them at the local shop.

Ruby commented, that in the winter months cows are usually ‘dry’ and calving but Father still had plenty to do. He would go into their woods, and bring out the huge trees, and ‘skin’ them ready for the warmer months, and on the first day of February, he would go to the river and cut huge ice blocks, bring them back and store them in sawdust in the barn, ready for the ice-box in the summer.

When spring came, the cows had fresh green grass, and a herb called Sorrel that they loved to eat, the butter was a beautiful yellow. In the winter, and early spring however, when the cows could not get the lush grass and herbs, Mother had to add a drop of carotene to make the butter look more attractive.

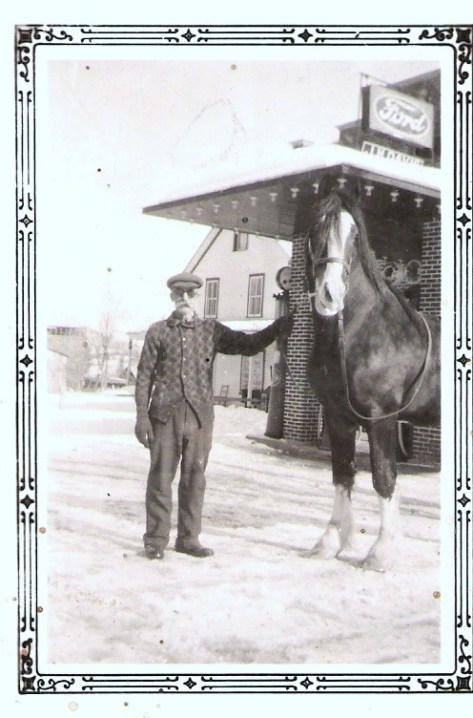

The barn which Father built by hand, was very large, clean and warm and held the cows and two Clydesdale horses. Clydesdale’s can grow to over 18 hands tall. A hand is four inches, so this would be 72 inches or 6 feet. A horse is measured from the ground to its withers. If you feel at the end of a horse’s mane, you will find a small flat spot, which is the withers. [4]

RUBY’S FATHER WITH THE CLYDESDALE HORSE

Ruby said that the horses drank an enormous amount of water daily and they had to have their water buckets filled three times a day. They were gentle and calm and the children never felt afraid being in their presence, unlike the Jersey cows! One day, she said, one of the Jerseys kicked her younger sister for no reason and the next day, Father sold her! The Jersey cow, not the sister.

The barn was kept free of rodents by the barn cats, who were never allowed in the house, but fed daily at milking with warm milk given to them on the porch by Mother. The house was lit by oil lamps until Ruby left home at 16 and for a few years afterwards. On a Saturday, it was Ruby’s job to wash the glass chimneys trim the wicks and fill all the lamps in the home. She would also walk to Christieville a long walk, to pick up the mail and shop.

The cast iron wood stove was where Mother did all of her cooking and baking. Ruby said, Mother never made cookies, they were too expensive! Everything else was home made. During the hot days doors and windows were always kept open for a clear draft through the house, to cool the cook.

The girls went berry picking in the summer, looking out for bears whom they could see had left their imprint, whilst they too, picked the berries. Always on 12 July, next to the river, they had a celebration picnic of the ‘Glorious 12th’ an Irish holiday celebrating the Battle of the Boyne where the Protestant King, William of Orange ‘beat the Catholics’ in 1690.

Ruby was home schooled until she was about seven years old, as before that it was too far and too cold for a youngster to walk or ski to school. Of course, there were no school buses. Ruby frequently skied to school in winter and walked there and back in Summer. Occasionally, if the snow was very deep her father would hitch the Clydesdale’s to the sled and take them to school, but not very often as he was too busy!

The one room school house for the high school children, had one teacher, hired from England and he taught them every subject, at every level, including French with the curricular coming from England and exam results sent ‘away’ for marking. There was a total of 8 pupils in Ruby’s high school. At lunch time everyone including the teacher, brought the same thing every day – a peanut butter and jam sandwich, and occasionally a cookie or piece of cake, They drank water. In the summer they all played baseball after lunch and in the Winter, skied. Ruby had homework every single night, and that had to be done after household chores. Ruby left school after passing all her exams, when she was 16 years old.

RUBY’S ONE ROOM SCHOOL – RUBY ON THE FAR RIGHT

Whenever I download historic information regarding Morin Heights to read to Ruby, she points out that the people I am reading about were her uncles, cousins, her fathers’ brother, or mothers’ family and other family members. There is a Rural Route named after her family and there are many historical articles about the building of churches and other buildings, where her family names are mentioned frequently.

Her Irish/Quebec roots run deep and many of the pioneers of Morin Flats were connected to her or her family, friends or neighbours she remembers.

You can learn a lot from the elderly and I love talking to Ruby about many things, which I hope to continue for many a year, but her stories of her early years are the most interesting!

Sources:

[1 2] http://www.morinheightshistory.org/history.html

[3] http://www.morinheightshistory.org/census/1861MH.html

[4] http://www.clydesusa.com/faq/

……and particularly, my friend Ruby.

Ruby McCullough Clements passed away peacefully on 24 November, 2016, RIP.

Daniel Hanington and his wife, Margaret Ann Peters

Daniel Hanington and his wife, Margaret Ann Peters