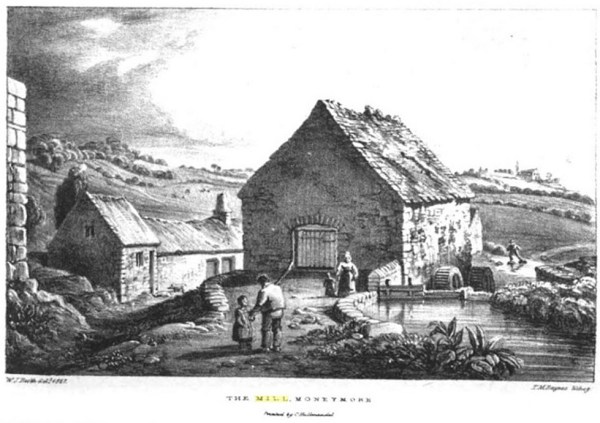

If you are looking for the old corn mill in Moneymore, Northern Ireland, turn off High Street in the village centre and go to the end of Mill Lane. It’s right there, although you might not guess that old stone building was once a busy mill since the water wheel has gone and the water that powered it flows in an underground river.

Long ago, this corn mill (corn refers to oats in Ireland) was a very important building in the community: this was where people brought their oats, wheat, barley, and rye to be ground into flour. In the mid-1700s, my five-times great-grandfather Benjamin Workman was probably well-known in Moneymore because he was the local corn mill operator.

His great-grandson recounted the family’s history in a journal, written around the 1850s.1 He explained that Benjamin’s father, William, had a mill (probably a flax mill) and a farm at Brookend, County Tyrone, several miles south of Moneymore. Benjamin inherited the Brookend property from his father, but he was unhappy there because he didn’t get along with the neighbours.

When Moneymore needed a new miller, Benjamin left Brookend and took the job in town. He was not the owner – he rented the mill from the Drapers’ Company of London, which owned most of the property in the area – but everyone paid him to grind their flour.

It was a good move for Benjamin, and for the area residents. According to the journal account, when he died around 1767, he was mourned by Protestants and Catholics alike.

This story may be backed up by historical data: the 1766 Religious Census of County Derry confirms that Benjamin Workman, Protestant Dissident (in other words, Presbyterian,) was a landholder in Moneymore Townland, Barony of Loughinsholin, Derry County.2 An earlier census of Protestant householders in Ulster, carried out in 1740, showed there were several individuals with the name Workman in the area.3

Benjamin Workman, miller of Moneymore, and his wife (whose name is unknown) had at least one son, also named Benjamin. According to the journal, he succeeded to the business and property interests in Moneymore, and, like his father, he died at an advanced age.

This Benjamin married Ann Scott and the couple had four sons and two daughters. All but one of them left Ireland, although two returned and settled in other parts of the island. Only daughter Letitia stayed in Moneymore. According to the journal, she married, first, a man named Scott, with whom she had a daughter, and second, a man named McIvor. Letitia had five more children with her second husband. She died in Moneymore in 1832.4

That is all I was able to discover about the Workman family in eighteenth-century Moneymore, so my curiosity turned to the mill and the town itself

More than 5000 mills were built in Northern Ireland, including 510 in County Derry (Londonderry) and 573 in neighbouring County Tyrone. There were several types, including corn, or grist mills, flax mills (flax is the plant that is used to make linen) and tuck mills (used to remove impurities from woolen cloth). Today, many have been demolished while others lie neglected, but studying them reveals much about the industrial and architectural history of the area.

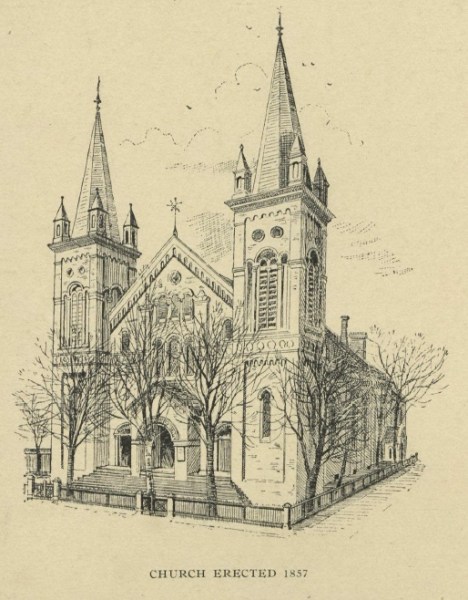

Moneymore’s corn mill was originally built around 1615, about the time Moneymore was founded. One and a half storeys high and 34 feet long, it was built almost entirely of wood, with a shingled roof. The smith at Moneymore provided most of the iron nails and fittings, the spindle shaft was manufactured in Ireland and other components were imported from London.5

It was rebuilt in 1785, but when a report was prepared on the plantation at Moneymore in 1817, the mill was found to be inefficient and in need of more repairs.6 Now, Sebastian Graham of the Mills of Northern Ireland heritage group, told me in an e-mail, “the mill is technically still there, but heavily changed. It became a flax mill as well as a corn mill around 1860 or so, and then a creamery.”

As for the village of Moneymore, located west of Lough Neagh, it was founded in the early 1600s as a part of a scheme to populate Ulster with Protestant settlers from England and Scotland. Ulster was the name of the northeastern part of the island of Ireland, now Northern Ireland and part of the United Kingdom. For decades, the English army fought the native Irish forces, but things turned in favour of the English at the end of the 16th century. The English confiscated the properties of the Irish chieftains in Ulster and, in 1608, launched a plan to create the Plantation of Ulster.

English and Scottish landlords were granted vast estates. In return, they were required to build towns, fortifications and houses, and to bring settlers to the area. They leased out properties of about 15 acres each, including cultivated land, turf-bogs and rough pastures, to tenant farmers.

The project required investors with deep pockets. The plantation of Moneymore was the property of the Drapers’ Company, a London trade association of wool and cloth merchants that had been founded in medieval times.

Like several other plantation-era villages, Moneymore was planned in a cruciform shape, with a marketplace at the intersection of two main streets. Proclamations were read out to the residents next to a tall wooden pole located beside the marketplace.

From the beginning, however, the Drapers did not meet all the goals the government in London had set out. The fortifications at Moneymore were poorly built, the houses were tiny and the native Irish population remained larger than the number of settlers. Surveys carried out in the early 1800s found the manor house was in bad shape, as were the mill and the tenants’ cottages.

Today, the manor house has been restored and Northern Ireland is peaceful. As I researched this topic, I discovered my husband and I visited the area near Moneymore in 2008, before I began researching my family history. If only I had known!

This story is also posted on my family history blog, http://www.writinguptheancestors.ca

Sources

1. Dr. Benjamin Workman, A Family Orchard: Leaves from the Workman Tree, Part 1. The Determinate Branch of the Compiler. Family History, Branch Introduction. https://freepages.rootsweb.com/~database/misc/WORKMAN.htm, accessed May 6, 2025.

2. 1766 Religious Census for some parishes in Co. Derry, https://www.billmacafee.com/1766census/1766religiouscensusderry.pdf, Bill Macafee’s website, Family and Local History, Databases compiled from 18th Century Census Substitutes, https://www.billmacafee.com/18centurydatabases.htm, accessed May 6, 2025.

3. Ireland, Ulster, Census of Protestant Households, 1740, results for Workman, Ancestry.com, https://www.ancestry.ca/search/collections/62769/?name=_Workman&count=50, accessed May 6, 2025.

4. Death notice for Letitia McIver; Belfast, Northern Ireland, The Belfast Newsletter, Birth, Marriage and Death Notices, 1735-1925, notice for Letitia McIver, Ancestry.com, accessed May 7, 2025, https://www.ancestry.ca/family-tree/person/tree/117115991/person/432122459458/facts

5. Philip Robinson, The Plantation of Ulster, Belfast: The Ulster Historical Foundation, 1994, p. 146.

6. Reports of the Deputations of The Drapers’ Company of Jan. 23, 1817, … Estates of the Company in the County of Londonderry, in Ireland. Google Books. Accessed May 7, 2025. P. 32.