(reposted from June 2020)

Charlotte Haines (1773-1851) was only ten years old when the breakaway 13 colonies won the War of Independence in April 1783. Those residing in the new United States of America, who had remained loyal to the British Crown, were persecuted and forced out of their homes and their belongings seized. Chaos reigned everywhere and families were torn apart.

One fateful day around this time, young Charlotte sneaked away to visit her British Loyalist cousins, against the expressed wishes of her American Patriot stepfatheri. Upon her return, standing outside the front door, he refused her entry back into the family home.

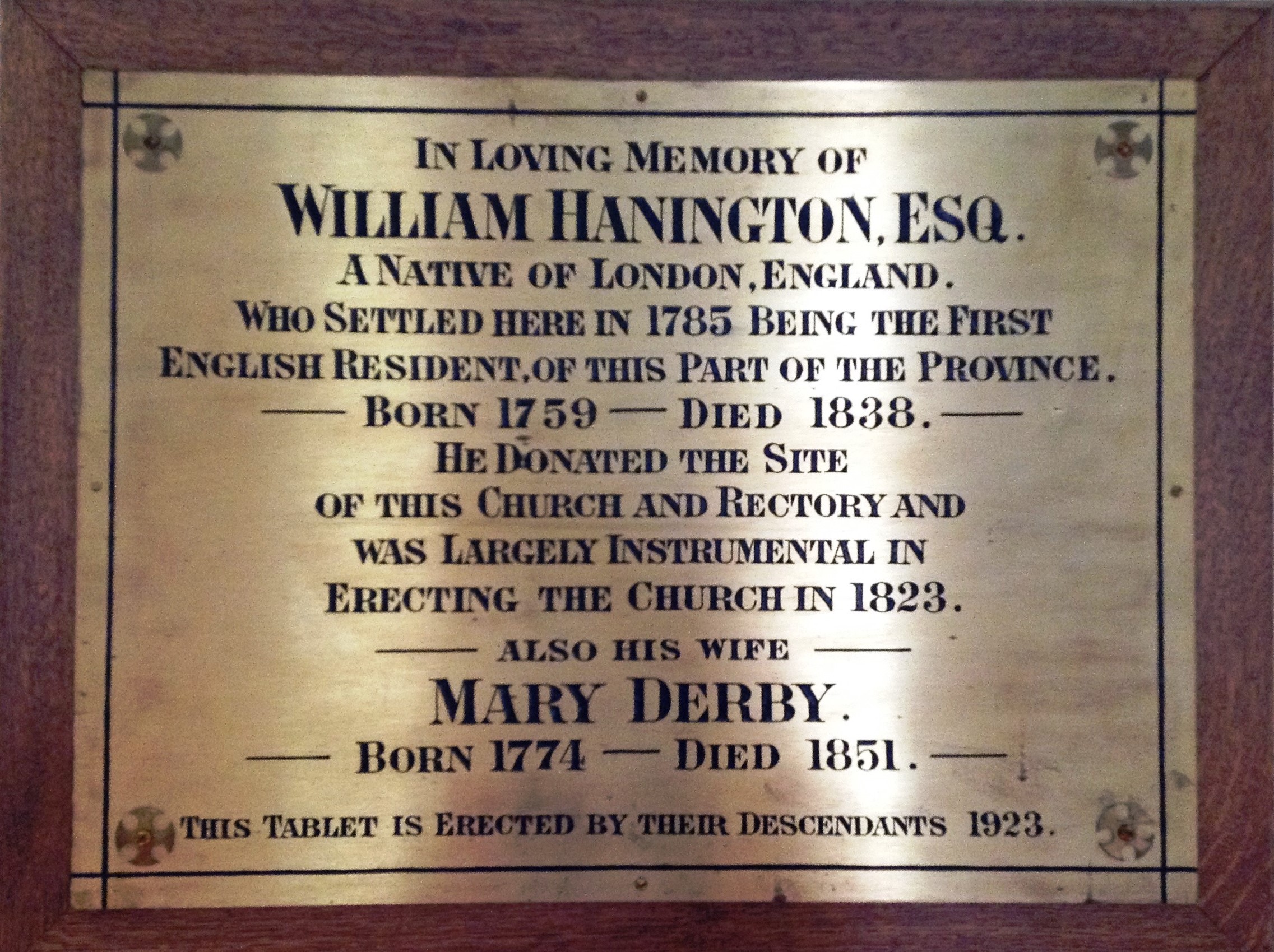

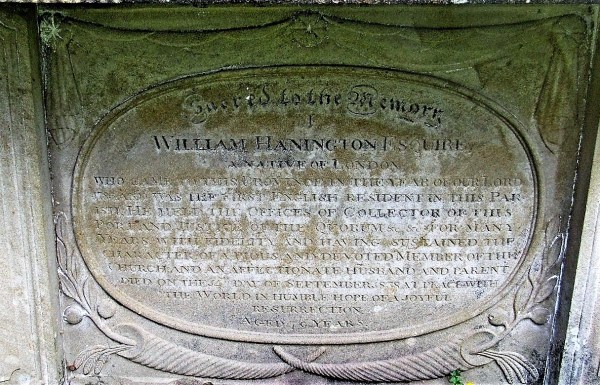

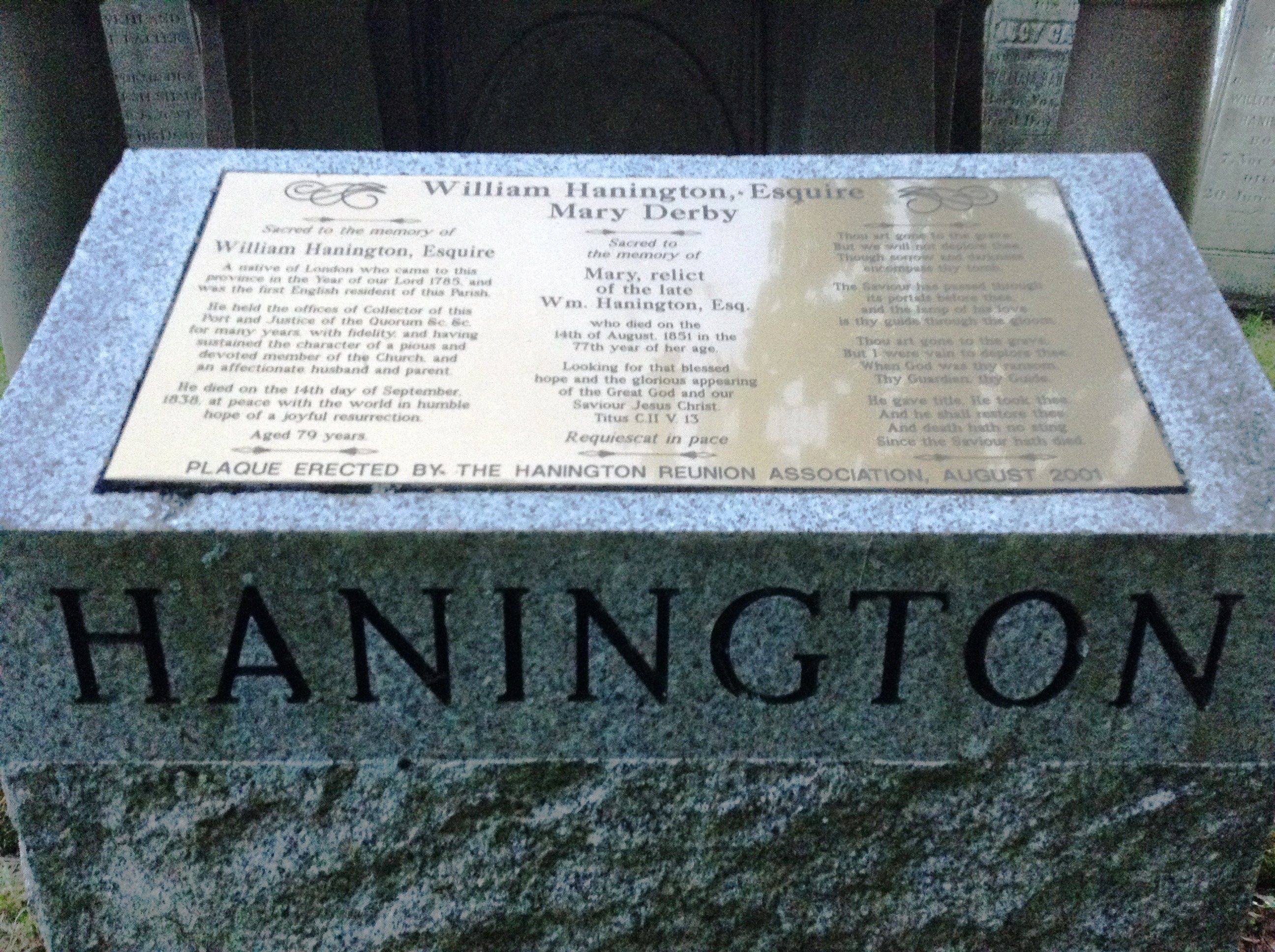

Charlotte was my three-times great-grandmother. Her daughter Margaret Ann Peters married Daniel Hanington and their son James Peters Hanington was my grandmother’s father.

The British government came to the aid of these Loyalists and arranged for transportation for those who wished to leave the new America. Charlotte’s grandparents, Gilbert and Anna Pugsley, rescued young Charlotte and her brother David. Together they sailed from New York for ten days on the “Jason”ii, with 124 other “refugees” as part of the final large scale evacuation and landed in New Brunswick (then still part of Nova Scotia) in October 1783…just in time for the brutally cold winter.

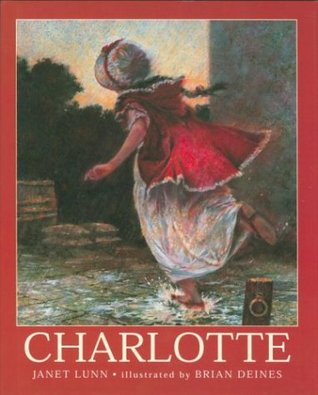

Charlotte has been the favourite subject of a couple of books and several folktales. She warranted her own chapter in “Pioneer Profiles of New Brunswick Settlers”iii and is the main character in a children’s book titled “Charlotte”iv. One folktale claimed that she was the first Loyalist to set foot ashore (not true) and in doing so, she lost her “slipper” in the mud (possibly). The matching slipper (unlikely) was donated to the New Brunswick Museum years later, however, it looks somewhat too big and stylish for a ten-year old girl. But they make wonderful stories and fully recognize young Charlotte as one of the first “petticoat pioneers” of New Brunswick.

Fourteen thousand Loyalists established a new settlement in 1783 along the St. John River and shortly afterwards they petitioned for their own colony. In 1784, Great Britain granted their request and divided Nova Scotia into two — New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. The Loyalists, who made up 90 percent of the population of New Brunswick, became a separate colony with its capital, Fredericton, 90 miles upriver from Saint John.

The Loyalists and their children were entitled to free land once they provided the necessary proof. Charlotte, as the biological daughter of John Haines, a Loyalist on record, appears in 1786 documentation as one of the grantees of 84 lots on Long Island, Queen’s County, along with several other prominent Loyalists – although she was only 13 at the time. I can imagine her grandfather Pugsley nodding discreetly in her direction as he looked after her interests.

For their first three years, the British provided the Loyalists with a few simple tools, blankets, material for clothing and seeds for wheat, peas, corn and potatoes. The rations of basic food supplied by the British supplemented the abundance of game and fish available to them in the forest and streams. Most lived in tents on dirt floors until they were able to build primitive log cabins. Tree by tree, stump by stump, the fertile uplands were cleared to widen the fields making them ready for crops.

The Loyalists kept meaningful social contacts through various community events. Neighbours organized “frolics” whereby the men would work together to clear land, move rocks, build a barn or complete some other task which proved impossible for one or two people. At the same time, the women prepared meals and the children had a chance to play with friends. Women also held their own frolics to make quilts, card wool or shell corn. These Loyalist neighbours were dependent on one another in times of sickness, accidents and childbirth and supported one another at gatherings for weddings, funerals and church services.

Perhaps Charlotte met her future husband at one of these popular frolics. At 17, Charlotte married William Peters (also from a United Empire Loyalist family) in 1791 in Gagetown. Soon afterwards, the happy couple moved downriver, settled in Hampstead and built a home where the St. John River widens to a magnificent view.

At that time, there existed only ten miles of roadway in the whole province and another 20 years would pass before there would be an 82-mile long road linking Fredericton and Saint John. However, in the meantime, the river served as a “highway” enabling the transport of passengers and necessary goods between the two cities.

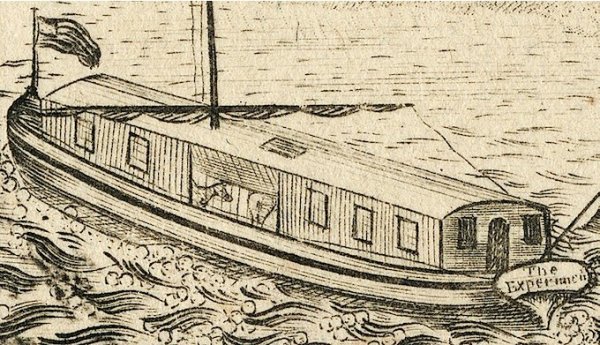

When the steamboats first chugged noisily up the river in 1816, William decided to compete with them and he built a 100-foot long side wheeler powered by 12 horses walking up and down the deck and propelling the boat along.

William actively pursued his interest in politics, and as the first representative of Queen’s County in the New Brunswick Legislature, he spent a lot of time in Fredericton (50 miles away) attending the sessions of Parliament.

Meanwhile, back home, Charlotte managed their entire land-holding on her own. Eventually they had 15 children, five sons and ten daughters. She bore her last child at 50 years old according to the baptismal certificate. They all survived except their son John who drowned at 21 attempting to save another man’s life.

Not only did she clothe, feed and care for them all (including the servants) but also provided much of their early education as well. On Saturday evenings in the summer, the fiddlers would play rollicking tunes and the tapping of dancing feet could be heard in big houses and cabins alike. When winter shut down the fields, and with food plentifully stored in the cellar, the spinning wheels would begin to hum during those coldest months.

By the time William died in 1836, they had recently relocated to Woodstock (100 miles upriver from Hampstead) with two of their younger children, James and Caroline. Their older children were married with homes of their own scattered along the St. John River Valley. Around this time, she wrote a letterv to her daughter Susan, Mrs. Thomas Tilley:

I take my pen to address a few lines to you to inquire after the health of you and all of your family. The grate distance we are from you prevents me from hearing. You heard of the death of your Father at Woodstock.

Charlotte described William’s death in some detail and then continued:

I hop [sic] this may find you all well. I am not well. My head troubles me very much. There is not one day that it don’t ake [sic] so that I cant hardly stir. My cough is something better. James and Caroline is well and harty [sic] and quite contented hear. I like the place and if your Father has lived and been hear to see to it we might have made a good living. It is pleasant and a good place for business but we must try to due the best we can. The place is out of repair and soon would have been a common if we had not come hear. I should be glad if my friends was near to us. I don’t know as ever I shall see you all again. I thought to have gon [sic]to see you all before I came up hear but I was so sick that I could not go down to see you. James and Caroline wishes to be remembered to you and all the family. I desire to be remembered to Thomas and the children and tel them I should be glad to see them and you. Give my love to all inquiring friends and except a share for yourself.

This from you afectionet [sic] Mother, Charlotte Peters

Although she had her share of aches and pains at that time, she lived another 15 years and ultimately enjoyed the blessing of 111 grandchildren.

She had a powerful influence over all her family for she believed that their heritage carried a great responsibility to others. When the grandchildren would visit, her graceful hands were always busy winding yarn or knitting a sock while patiently answering their questions and reciting passages from the bible.

One of her grandchildren, Samuel Leonard Tilley, later known as Sir Leonard, served as Premier of New Brunswick and went on to became one of the Fathers of Confederation.

A common tale states that Tilley proposed the term “Dominion” in Canada’s name, at the London conference in 1866, which he gleaned from Psalm 72:8 – “He shall have dominion also from sea to sea, and from the river unto the ends of the earth”. Ultimately, as Minister of Finance in the federal government, he was also instrumental in seeing the transcontinental railway completed.vi

Young Charlotte Haines might have felt all alone in the world at age ten but, when she died 68 years later, the epitaph on her tombstone proclaimed her legacy: “…Lamented by a large circle of descendants and friends by whom she was universally beloved and respected.”

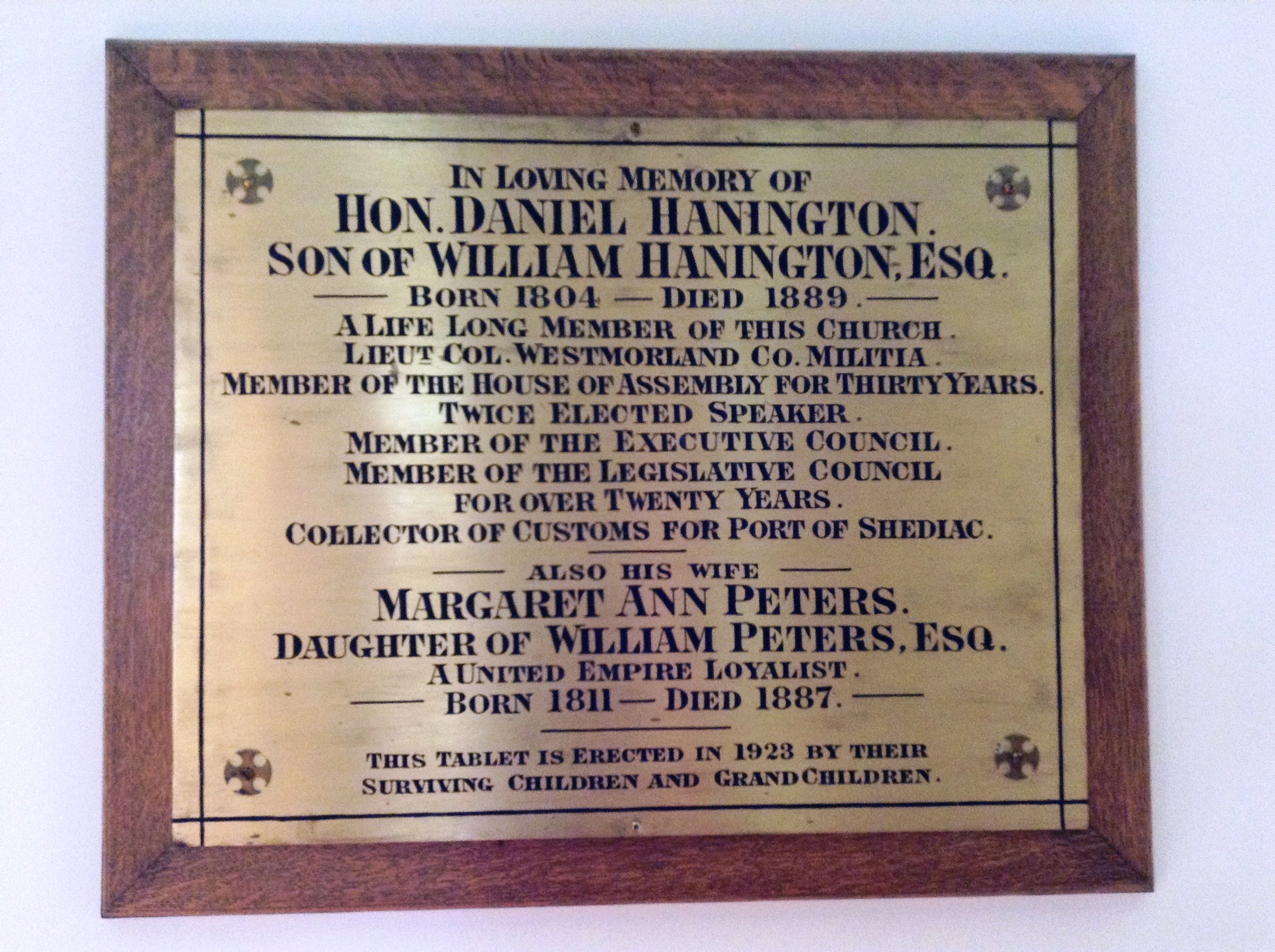

Charlotte’s daughter Margaret Ann Peters and her husband Daniel Hanington “Roaring Dan” (my great great grandparents).

Notes:

iCharlotte’s mother, Miss Pugsley, died when she was very young. Charlotte’s father remarried Sarah Haight before he died. Then Sarah remarried Stephen Haviland who was Charlotte’s stepmother’s husband (step step father?)

iiThe Ship Passenger Lists, American Loyalists to New Brunswick, David Bell, http://www.uelac.org/Loyalist-Ships/Loyalist-Ships.php as seen 2020-03-28

iiiCharlotte Gourlay Rovinson, Pioneer Profiles of New Brunswick Settlers, (Mika Publishing Company), 1980, p.143.

ivJanet Lunn, Charlotte, (Tundra Books), 1998.

v https://queenscountyheritage.wordpress.com/2011/09/28/loyalist-of-the-day-charlotte-haines-peters/ as seen 2020-04-02

vi Conrad Black, Rise to Greatness: The History of Canada, (Random House), 2014.

Image – https://wiki2.org/en/Experiment_(horse-powered_boat) as seen 2020-06-11