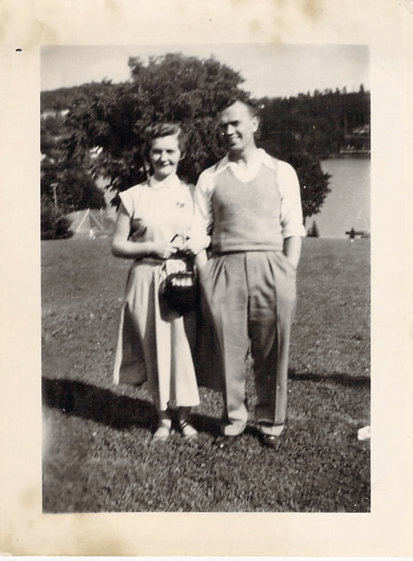

My aunt, Sarah Jane McHugh, was delighted to host the linen shower to celebrate her daughter, Dawna Day’s upcoming marriage to Ralph Dodds. The happy couple announced their engagement in October 1947. Ralph had recently been discharged after serving in the Royal Canadian Navy for over six years. The couple’s wedding would take place in Vancouver, Ralph’s home town. Dawna was from Montreal.

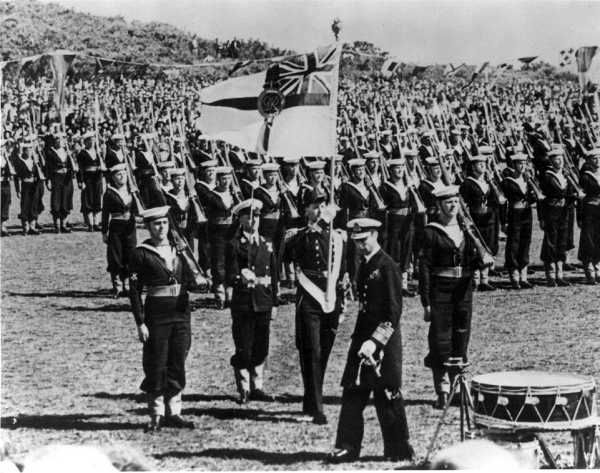

Ralph was just 20 when he started his navy career in Esquimalt, British Columbia in 1939.1 With the advent of World War II, the Esquimalt Navy base became the largest naval training center in western Canada. 2 Ralph Dodds trained to become a signalman would have learned all aspects of military communications in the Canadian Navy. He would have used semaphore flags, read and transmitted morse code messages, and assured radio communications.3 During his training, Ralph would not have predicted that he would participate in the sinking of a German U-boat during the Battle of the Atlantic, that he would be on a destroyer that participated in a sea fight on D-Day, or that the destroyer he was on would be shipwrecked off the coast of Iceland.

While Ralph was assigned to a naval station, and to a corvette (small destroyer), for most of his naval career, he was assigned to the HMCS Skeena.

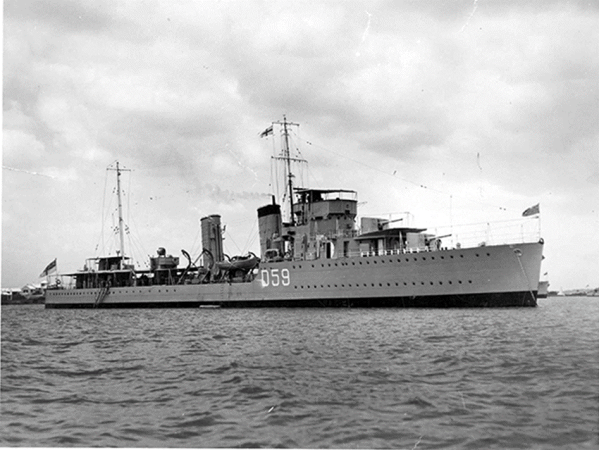

The HMCS Skeena was commissioned in 1931 in Portsmouth, U.K. and was one of the first two ships built to Canadian order. With the outbreak of the war, the Skeena initially performed domestic escort duties. In May 1940, she was sent to Plymouth, U.K. and became part of the Western Approaches Command, taking part in the evacuation of France and escorting convoys in British waters. She was later assigned to continuous convoy duty.

During one of its escort duties in the Atlantic, the Skeena destroyed U-boat U-588. This happened during ON-115 (ON means Outbound to North America). There were twelve escort ships for a trade convoy of 43 merchant ships that left Liverpool on July 12, 1942. On July 29, seven U-boats of the Wolfpack Wolf had spotted them. This Wolfpack was quickly joined by another six U-boats of the Wolfpack Pirat. The Wolf Pack tactic, or the “Rudeltaktik,” was devised to attack the Allied convoy system by forming into position effecting a massed organized attack.4 This particular battle resulted in the loss of three of the ships in the convoy and significant damage to two of the ships in the convoy. One of the damaged ships returned to the U.K. and one was escorted to St. John’s, Newfoundland. The Skeena, on which Ralph was a signalman, and the HMCS Wetaskiwin, an escort corvette, destroyed U-boat 588 with depth charges (antisubmarine missiles) on July 31. The hostilities lasted until August 3 when the U-boats lost contact with the convoy due to misty weather. The convoy with the remaining ships reached Boston on August 8, 1942.5

The Skeena also participated in a hot sea fight in the Channel on D-Day. The Skeena’s assignment was to prevent enemy U-boats from attacking Allied ships while the Invasion of France was being carried out.

“Torpedoes were shooting about in the Channel and missed the Skeena by only a matter of feet,” said Ralph in an interview he gave to the Vancouver Sun.

The destroyer also had to contend with German Dorniers (bombers) that were bombing the destroyers in the Channel. One of the aerial missiles fell so close to the Skeena that shrapnel was later found on the deck.6

After five years of war, the HMCS Skeena met her end as she sheltered from a violent gale with 15-metre waves off the coast of Iceland, at Videy Island on October 24, 1944. Even though the crew had thrown out a second anchor to secure the ship, the Skeena smashed into the rocks. When the crew abandoned ship, the men were unable to hold the lines. Some crew members were smashed into the rocks, while others were tossed into the sea. Fifteen sailors died.7 Ralph Dodds survived.

- Vancouver Sun, D-Day Fight in Channel Recalled by B.C. Sailor, 13 December 1944.

- Vance, Emily. Capital Daily, How Canada’s Pacific Fleet Shaped Greater Victoria Over Two Centuries, 1 May 2021, https://www.capitaldaily.ca/news/canadas-pacific-fleet-greater-victoria-two-centuries, accessed 24 July 2023.

- Wikipedia, Signaller, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Signaller, accessed 24 July 2023.

- Uboataces, German U-Boat, U-Boat Tactics, The Wolf Pack, http://www.uboataces.com/tactics-wolfpack.shtml, accessed 31 July 2023.

- Wikipedia, Convoy ON115, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Convoy_ON_115, accessed 26 July 2023.

- Vancouver Sun, D-Day Fight in Channel Recalled by B.C. Sailor, 13 December 1944.

- Military History Now, HMCS Skeena – Meet One of the Toughest Warships of the Battle of the Atlantic, 12 November 2020, https://militaryhistorynow.com/2020/11/12/hmcs-skeena-meet-one-of-the-toughest-warships-of-the-battle-of-the-atlantic/, accessed 2 August 2023.