Update: January 24, 2024

Since this story was originally published, the City of Montreal has added a poster next to Metro Champs de Mars to make it clear that Marie-Josèphe Angélique’s park will be within the Place de Montrealais!

Thanks to Annie for letting me know, and thanks for everyone who made sure that her story is not forgotten!

For an hour on the first cold day of the year last month, I wandered around City Hall looking for the memorial park named after an enslaved woman whose torture led to her conviction for arson in 1734. She was then ridiculed, hanged, and her body was burned to ashes and thrown to the wind.

I couldn’t find it.

I’m not sure what happened from the time the park was created in 2012 to today, thirteen-and-a-half years later, but the one-time park still appears on Google Maps. In person, I couldn’t find anything to indicate where it might be.

According to various articles on the web, a green space just west of Champs de Mars métro station honours Marie-Josèphe Angélique’s memory. The official inauguration of the park took place on Aug. 23, International Day for the Remembrance of the Slave Trade and its Abolition, 2012.

As I walked through the area last month, the one-time park seemed to be encompassed in a massive construction site underway for Place des Montréalais, a new public space being created next to the Champ des Mars metro on Viger Street. The posters on site explaining the current project included nothing about Marie-Josèphe Angélique.

Despite being honoured with an award-winning film, a bronze plaque, lilies and a presentation by Governor General Michaelle Jean in 2006, and a public park created by the city of Montreal in 2012, she’s disappeared again.

Before this experience, I was already struggling to see Angélique as the symbol of freedom and resistance she serves for many, but I don’t want her to be forgotten. Did she set the fire or was she a convenient scapegoat? If she didn’t, who did? As I began exploring her story last month as part of a project for NANOWRIMO (the National Novel Writing Month), she served as a reminder of the kind of unnecessary suffering a biased political, policing and justice system can create. Despite the fact that she was a victim of slavery, hatred, spite, racism, class bullying and the worst that a mob could throw at her, her spirit remained strong and unrelenting.

Angélique proclaimed her innocence until the day she was tortured, throughout the court case, and through questioning. Despite that, three weeks after the fire, she was hanged, ridiculed publicly, then burned with her ashes tossed into the wind. Clearly, the authorities at the time wanted her punishment to be seen and remembered.

I read the details about Marie-Josèphe Angélique’s case on Torture and the Truth, a fabulous website set up in 2006 by multiple people, including one of my genealogical mentors, Denyse Beaugrand-Champagne and one of my historian mentors, Dorothy W. Williams. Both of these women have researched, written, spoken and taught many people about the history of Montreal and why studying it is so important.1

The site is one of thirteen different “historical cold cases” established for classrooms across Canada. It was created through the work of six writers, a photographer, an artist, and two translators collaborating with six funding agencies, seven production partners, and 15 archive and museum partners.

It is one of the best historical websites I’ve ever read. If you do nothing other than read through this site, you will get a good overview of the community, the victim arsonist, and life in early Montreal.

As I read about Angélique’s story, she sounded like just the kind of person anyone would like to get rid of. She was a woman who told people she would burn them alive in their homes. She said so to her owner for refusing to grant her freedom, to other slaves for making her work harder than she wanted and to others too. To anyone who slighted her, she threatened the worst thing she could think of. She would burn their homes down.

When 45 houses in her small community did in fact burn down, people blamed her. In retrospect, it may have been an accidental kitchen fire that caused the flames, but her words came back to haunt them all.

The fire began at 7 p.m. on a Saturday evening in spring, April 10, 1734. In only three hours, it destroyed 45 homes and businesses on Rue Saint Paul. Even the Hôtel-Dieu hospital and convent, where people initially took shelter, burned to the ground. Hundreds of people were left in the cold; supplies from many merchants burned, never to be seen again.

Plus, who knows how many caches of fur got wiped out. At that time, Montreal was the centre of the fur trade, more than half of which was illegal trading with the Dutch and English communities in Albany, Boston and other communities to the south. According to a 1942 thesis by Alice Jean Elizabeth Lunn, furs were stored in the backs of shops and even buried just beyond the Montreal wall, which was still under construction at that time, in order to be shipped without being seen by New France authorities. A lot of money went up in smoke that day.2

Everyone in Montreal knew about the fire, given that all the church bells throughout the city began ringing when it started and continued until it was over and people were safe again. Although stone buildings existed at the time, most of the buildings were made of wood; fire could destroy them all.

I had ancestors who lived in Montreal then, the Hurtubise clan on my father’s mothers side. One of them, Jean Hurtubise, the grandson of Étiennette Alton and Marin Hurtubese, was thirty-nine years old, ten years older than Angélique when the fire took place. He and his wife Marie-Jeanne (Marie-Anne ou Marianne) Tessereau had been married for seven years in 1734.

Jean was born in Ville Marie and lived in Montreal for his entire lifetime, so he and his family would have experienced the fire, at least from a distance. They certainly would have seen the ordinance compelling witnesses to appear, given that “it was posted and cried out everywhere in the city and its suburbs.”

Jean and his family farmed a 3×20 arpent property they bought three years earlier from Raphael Beauvais and Elisabeth Turpin on Rue Côte Saint-Antoine.”3 The property was in a part of Montreal that was considered the countryside at that time. Their home was then one of four wood houses on Côte Saint-Antoine in 1731.4

Given that the area was still very rural, and on a major hill, I can’t help but wonder. Did they see the smoke rising into the sky as the hospitals and 45 other buildings in Ville Marie were destroyed?

They certainly had strong links to Ville Marie, particularly the hospital. His grandmother, Etionnette Alton, had died there in her 84th year twelve years earlier. They couldn’t have helped wondering what would happen to others like her, being treated in the hospital that the fire destroyed. Were they among the crowd clamouring for revenge? Did they go to Ville Marie to see Angelique hanged? Did they watch her corpse burning? Did they see her ashes spread into the wind? Did they care at all?

I can’t help but imagine that the controversial hanging effected all 2000 people who lived on the island that year. Five years after Angélique’s death, Jean built Hurtubise House, a storey-and-a-half fieldstone structure on land originally rented by his father in 1699 on Mount Royal. The family built the gabled home out of stone to protect themselves from fire, as required by a law passed the summer after Angelique’s death. You can still visit the home today.5

1 Beaugrand-Champagne, Denyse, Léon Robichaud, Dorothy W. Williams, Marquise Lepage, and Monique Dauphin, “Torture and Truth: Angélique and the Burning of Montreal,” the Great Unsolved Mysteries in Canadian History Project, 2006, https://www.canadianmysteries.ca/sites/angelique/accueil/indexen.html.

2 Lunn, A. J. E. Economic Development in New France, 1713-1760. McGill University, 1942, https://books.google.ca/books?id=rtcxvwEACAAJ.

3 Roy, Pierre-Georges,, Inventaire des greffes des notaires du Régime français, Québec, R. Lefebvre, Éditeur officiel du Québec, 1942, 28 vol. ; 25-27 cm, Collections de BAnQ.

4 MacKinnon, J. S. The Settlement and Rural Domestic Architecture of Côte Saint-Antoine, 1675-1874. Université de Montréal, 2004. https://books.google.ca/books?id=IEJ4zQEACAAJ.

Written by Janice Hamilton, with research by Justin Bur

Note: there were three generations named Stanley Bagg, so for the sake of brevity I use their initials: SCB for generation two, Stanley Clark Bagg, and RSB for generation three, Robert Stanley Bagg.

Be careful what you wish for, especially when it comes to writing a will and placing conditions on how your descendants are to use their inheritance. That was a lesson my ancestors learned the hard way.

It took a special piece of provincial legislation in 1875 and what appears to have been a family crisis before these issues were finally resolved many years later.

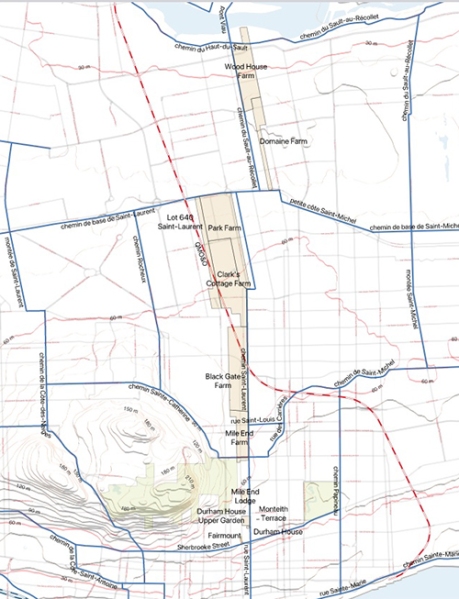

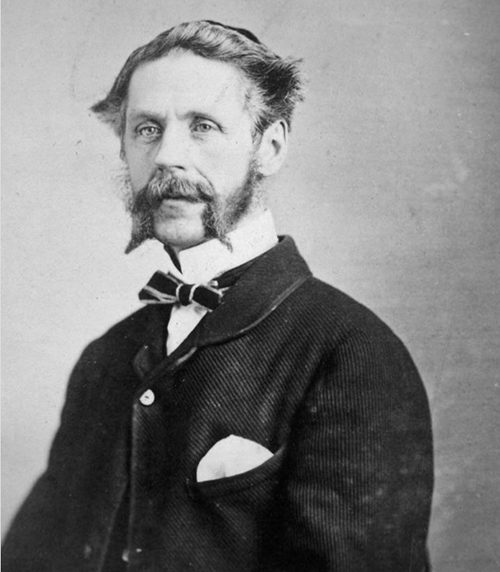

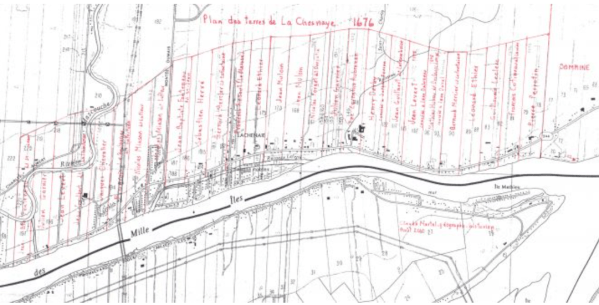

The estate at the heart of these problems was that of the late Stanley Clark Bagg (1820-1873), or SCB. He had owned extensive properties on the Island of Montreal. Several adjacent farms, including Mile End Farm and Clark Cottage Farm, stretched from around Sherbrooke Street, along the west side of Saint Lawrence Street (now Saint-Laurent Boulevard), while three other farms extended along the old country road, north to the Rivière des Prairies. SCB had inherited most of this land from his grandfather John Clark (1767-1827). Although he trained as a notary, SCB did not practise this profession for long, but made a living renting and selling these and other smaller properties.

At age 52, SCB suddenly died of typhoid. In his will, written in 1866, he named his wife, Catharine Mitcheson Bagg (1822-1914), as the main beneficiary of his estate, to use and enjoy for her lifetime, and then pass it on to their descendants. He also made her an executor, along with his son Robert Stanley Bagg (RSB, 1848-1912). There were two other executors: Montreal notary J.E.O. Labadie and his wife’s brother, Philadelphia lawyer McGregor J. Mitcheson.

But SCB’s estate was large and complicated, and no one was prepared to handle it. RSB had recently graduated in law from McGill and was continuing his studies in Europe at the time of his father’s death. As for Catharine, she became involved in decisions regarding property sales over the years, but she must have felt overwhelmed at first.

Notary J.A. Labadie spent two years doing an inventory of all of SCB’s properties, listing where they were located, their boundaries, and when and from whom they had been acquired, but he did not mention two key documents. One of these was the marriage contract between SCB’s parents, the other was John Clark’s will.

In the marriage contract, John Clark gave a wedding present to his daughter, Mary Ann Clark (1795-1835), and her husband, Stanley Bagg (1788-1853): a stone house and about 22 acres of land on Saint Lawrence Street. Clark named the property Durham House. But it was not a straight donation; it was a substitution, similar to a trust, to benefit three generations: Mary Ann’s and Stanley’s child (SCB), grandchildren (RSB and his four sisters) and the great-grandchildren. Each intervening generation was to have the use and income from the property, and was responsible for transmitting it to the next generation. That meant SCB could not bequeath it in his will because his children automatically gained possession, and so on, with the final recipients being the great-grandchildren.

In his 1825 will, Clark had made an even more restrictive condition regarding the Mile End Farm. This time the substitution was intended to be perpetual “unto the said Mary Ann Clark and unto her said heirs, issue of her said marriage and to their lawful heirs entailed forever.”

Perhaps Clark imposed these conditions on his descendants for sentimental reasons. Durham House was his daughter’s family home, and Stanley Bagg had probably courted Mary Ann on the Mile End Farm while he was running a tavern there with his father. Or maybe Clark simply believed that these provisions would give the best financial protection to his future descendants. SCB must have thought this was a good idea because his will also included a substitution of three generations.

Clark and SCB did not foresee, however, that the laws regarding inheritances would change. In fact, the provincial government changed the law regarding substitutions a few months after SCB wrote his will. This new law limited substitutions to two generations. Meanwhile, when SCB died in 1873, no one seems to have remembered that the substituted legacies Clark had created even existed.

Real estate sales practices also changed over the years. Clark had written a codicil specifying that any lot sales from the Mile End Lodge property, where he and his wife lived and which he left to her, were subject to a rente constituée. The buyer paid the vendor an amount once a year (usually 6% of the redemption value), but it was like a mortgage that could never be paid off. In the early 1800s this had been a common practice in Quebec, designed to provide funds to the seller’s family members for several generations.

SCB similarly stipulated that nothing on the Durham House property could be sold outright, but only by rente constituée. By the time he died, some of the properties located near the city outskirts were becoming attractive to speculators and to people wanting to build houses or businesses, but the inconvenience of a rente constituée was discouraging sales. It became clear that the executors had to resolve the issue.

They asked the provincial legislature to pass a special law. On February 23, 1875, the legislature assented to “An Act to authorize the Executors of the will of Stanley C. Bagg, Esq., late of the City of Montreal, to sell, exchange, alienate and convey certain Real Estate, charged with substitution in said will, and to invest the proceeds thereof.” (According to the Quebec Official Gazette, this was one of about 100 acts that received royal assent that day after having been passed in the legislative session to incorporate various companies and organizations, approve personal name changes, amend articles in the municipal and civil codes, etc.)

This act allowed the executors of the SCB estate, after obtaining authorization from a judge of the superior court, and in consultation with the curator to the substitution, to sell land outright, provided that the proceeds were reinvested in real estate or mortgages for the benefit of the estate. In other words, the rente constituée was no longer required, and sales previously made by the estate were considered valid.

No more changes were made until 1889, when family members realized that part of SCB’s property actually belonged to his children, and not to his estate, and a family dispute erupted. The story of how they resolved this issue and remained on good terms will be posted soon.

This article is also posted on my personal family history blog, http://www.writinguptheancestors.ca

Notes and Sources:

I could not have written this article without the help of urban historian Justin Bur. Justin has done a great deal of historical research on the Mile End neighbourhood of Montreal (around Saint-Laurent Blvd. and Mount Royal Ave.) and is a longtime member of the Mile End Memories/Memoire du Mile-End community history group (http://memoire.mile-end.qc.ca/en/). He is one of the authors of Dictionnaire historique du Plateau Mont-Royal (Montreal, Éditions Écosociété, 2017), along with Yves Desjardins, Jean-Claude Robert, Bernard Vallée and Joshua Wolfe. His most recent article about the Bagg family is La famille Bagg et le Mile End, published in Bulletin de la Société d’histoire du Plateau-Mont-Royal, Vol. 18, no. 3, Automne 2023.

Documents referenced:

Mile End Tavern lease, Jonathan Abraham Gray, n.p. no 2874, 17 October 1810

Marriage contract between Stanley Bagg and Mary Ann Clark, N.B. Doucet, n.p. no 6489, 5 August 1819/ reg. Montreal (Ouest) 66032

John Clark will, Henry Griffin, n.p. no 5989, 29 August 1825

Stanley Clark Bagg will, J.A. Labadie, n.p. no 15635, 7 July 1866

Stanley Clark Bagg inventory, J.A. Labadie, n.p. no 16733, 7 June 1875

Quebec legislation: 38 Vict. cap. XCIV, assented to 23 February 1875

See also:

Janice Hamilton, “Stanley Clark Bagg’s Early Years,” Writing Up the Ancestors, Jan. 8, 2020, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2020/01/stanley-clark-baggs-early-years.html

Janice Hamilton, “John Clark, 19th Century Real Estate Visionary,” Writing Up the Ancestors, May 22, 2019, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2019/05/john-clark-19th-century-real-estate.html

Judging from her family tree, my late mother, Marie Marthe Crepeau was a bona fide French Canadian de souche.1

Her father, Jules Crepeau, son of an entrepreneur painter from Laval and her mother, Maria Roy of Montreal, daughter of a master-butcher, have trees that go right back to the boat in France – and yes, mostly to Normandy, Poitou and Ile de France. Classic!2

And yet, according to Ancestry’s (beta) chromosome browser, my mother was not 100 percent “French.”

I’ve provided my own spit to the platform and apparently chromosomes 3 and 12 on her side are English (but that does include the North of France) and chromosomes 17 and 18 are Norwegian (Norsemen -Northmen-Normandy, perhaps?) And a swath of chromosome 2 is indigenous American, making me less than one percent indigenous.

Lately, I’ve subscribed to an interesting infotainment3 website that really dives into a person’s ethnicity from all angles and over a slew of time periods: Ancient, Bronze , Iron and Modern Ages. Sure, I get Eure, Finistere and Vendee (Normandy, Brittany and Poitou) in spades, but I get just about every other area of France, too – as well as some Spanish, French Corsican and French Basque.4

My mom’s French Canadian family tree supports some of this. From the ten percent sample I traced back to France I get natives of Limousine, Aquitaine, the Mid-Pyrenees, Picardy, Bourgogne, Haute-Marne, Bayonne, Les Rhones Alpes, as well as the Canadian North (Innu).5

And let’s not forget my ancestor the legendary pioneer river pilot Abraham Martin dit L’Ecossais (he of the Plains of Abraham fame) who may have been from Scotland. My mom has him at least twice in her tree.

A while back, I figured out that my Mom’s paternal Crepeau line (father’s father’s father, etc.) can be traced back to Vendee but it is likely of Sephardic Jewish ethnicity and hails originally from Spain. 6

In New France, my grandpapa Crepeau’s maternal tree can be traced to the original families at the Lachenaye (Terrebonne) Seigneury (est.1673) north east of Montreal, four founding farmer families in particular: Ethier (Poitou-Charentes), Forget (Normandy), Hubou (Ile de France) and Limoges (Rhones Alpes). My mother’s DNA is largely a mish-mash of these families’ genes, for they inter-bred down through the centuries. Basil Crepeau my mom’s 4 x GG was a slightly later arrival at Lachenaye who moved in beside the Hubous.

Now DNA distributes down the generations in very complicated and irregular ways especially where endogamy or founder effect is concerned8 and judging from my many French Canadian ‘cousins’ on Ancestry, my mom may have gotten a disproportionate amount of her genetic material from the Hubou founder family at Lachenaye Seigneury. A great majority of my DNA cousins on that platform are connected to me through her 2nd great grandfather, Michel Hubou dit Tourville.9

As it happens, Michel’s pioneer ancestor was one Mathieu Hubou dit Deslongchamps, a master-armourer from Normandy who was married to one Suzanne Betfer who was…wait for it… a gal from Gloucester, UK.

Now, ain’t that fun! A bona fide English Fille de Roi!!

THE END

1. de souche a controversial label that means from the roots.

2. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.07.20.500680v1.full.pdf On the genes, genealogy and geographies of Quebec. According to: French Canadians come from 8500 founder families in 17th and 18th century, with only 250 of these founder families, the majority from Perche, leaving behind the majority of genetic disorders that passed down through the ages. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41464974

(Hereditary disorders in the population of Quebec II Contribution of Perche)

The very first pioneers, the 2,700 super founder families, 1608-1680, were 95 percent French. The later 17th and 18th century founder families were 80-85 percent French but the non-French includes Acadians.) The first 2,700 founder families contributed to 2/3rds of the modern gene pool of French Canadians, but geography and natural boundaries kept families within even smaller gene pools. Indigenous DNA contributed one percent of French Canadian DNA. Regions can have super-founder families that contributed even more to the modern gene pool.

3. Your DNA Portal

4.These ethnicity estimates are based on complex science but the various results have to be taken with a grain of salt. Even if the original science is spot on, these results depend on what sample of your DNA is taken and how far back the algorithm is examining. I liken it to making a complicated stew from various ingredients, letting it simmer for a long time and then trying to deconstruct what it was made from. Maybe you put parsnips, carrots and parsley in the recipe, but these ingredients are already related genetically so it’s not easy to pull apart. Still, taken as a whole the results I get are telling: My mother’s ancestors were mostly from Gaul, especially the tribes Redones and Veneti in Brittany. Hardly a surprise as that’s what my Mom had always been told, that her people were from Brittany. I also get Gaul Santones who lived in Charentes. So spot on!

5. Nos Origines and Drouin

6.My mother is no outlier French Canadian in this respect, at least according to a recent paper that maintains that the Huguenot and Acadian populations are largely made-up of Sephardic Jews escaping the Inquisition. Investigating the Sephardic Jewish ancestry of colonial French Canadians through genetic and historical evidence. Hirschman.

https://nameyourroots.com/home/names/Crespo (Spanish roots likely Sephardic) The name means Curly Haired One. My mom knew that. She did have very curly hair as did her father so that trait passed down through the ages.

The Crepeaus (Crespeaus, Crespo’s Crepspin) are not the only possible Spanish line my mother has in her tree. For instance, her mother’s maternal Gagnon line goes back to one Lily Rodrigue in Normandy, a surname some say is Spanish derived. Another line goes to a Domingo in Bayonne, near the Spanish border. That name is Spanish/Italian and found in Southern France. I also have Navarre or Navarro. ADDED August 2025. I recently got two distant cousins – not related themselves on Ancestry Crespo and Crespim. Both mostly Spanish (very little 2 percent French) with 3 percent Sephardic Jew. Seems to prove my point.

7. Roy is the second most common surname in Quebec. http://leroy-quebec.weebly.com/the-surname-leroy.html . Gagnon is the third most common name and my direct pioneering ancestor hails from Perche in the North of France where he was a leading citizen, apparently.

8. Supposedly, all things being equal, we have only a 47 percent chance of inheriting DNA from an 8th GG, and inherited DNA from 8th GG’s amounts to a fraction of 1 percent but a high degree of endogamy or ‘founder effect’ clearly changes that, judging from the info in the studies in the links I have posted here.

9. On Ancestry, 60 percent of my closer DNA cousins are connected to me through Michel Hubou Tourville and his wife, but it should be noted that a full 400 family trees on Ancestry contain his name. It appears that his descendants moved to the US and did their family trees! Also, these ‘cousins’ tend to have my other Lachenaye names like Ethier and Forget and Limoges in their trees, so impossible to parse.

“This article explains the very thing I’m talking about: https://www.legacytree.com/blog/dealing-endogamy-part-exploring-amounts-shared-dna?fbclid=IwAR1veE4wNTc9gLGtx33Z8qphXmRdtTH2fREANxrenVDgx2NRqs1SznCAV0 “In one of our research cases, we found that an individual descended 12 different times from the same ancestral couple who lived in the late 1600s in French Canada. Although they were quite distant ancestors in every case (within the range of 9th-11th great grandparents), he had inherited a disproportionate amount of DNA from them due to their heavy representation within his family tree.”

Endogamy or consanguity? I’ve discovered that my grandfather Jules Crepeau likely had some double first cousins: his mother Vitaline Forget Despaties married Joseph Crepeau and Vitaline’s brother Adolphe Forget Despatie married Joseph’s sister, Alphonsine. I wonder if this happened further up the line. Wouldn’t that have messed with the DNA estimates! If such cousins marry it is closer to consanguinity than endogamy.

https://www.historyfiles.co.uk/KingListsEurope/BarbarianRedones.htm

The Celtic Tribes in France were described by the Romans as the GAULS.

I recently discovered two photos of “Amy” in my dusty old boxes of family memorabilia. The first captured her elderly wrinkled face with a twinkle in her eye and a flower corsage adorning her left shoulder and the other portrayed a 29-year old Amy dressed in a formal gown complete with a silk fan also with a flower corsage on her left shoulder. Inscribed on the reverse side of this second photo, written in Amy’s scrawl, was “Bob with love Amy – Xmas 1894.”

It turns out that Amy C. Lindsay (1865-1960) was my great grandfather Robert Lindsay’s (1855-1931) half sister. His mother Henrietta Dyde died within months of losing her fourth child and, a couple of years later, his father Robert A. Lindsay (1826-1891) married a young Charlotte Vennor (1843-1912) who became stepmother to his three boys – Robert, Charles and Percival – all under the age of ten. Over time, Robert A. and Charlotte had five more children, with Amy being their first born and ten years junior to Robert.

Who the heck was “Bob”?

Amy never married, so “Bob” could not have been a lost love in WW1, as she was 50 years old at that time. The most plausible explanation could be a gift to her older half brother Robert – “Bob” – and that’s the reason why the photo ended up in with my family.

My guess is that she idolized her oldest half-brother and gifted him that special photo which somehow survived the test of time to be found by me in my dusty old boxes. Mystery solved!

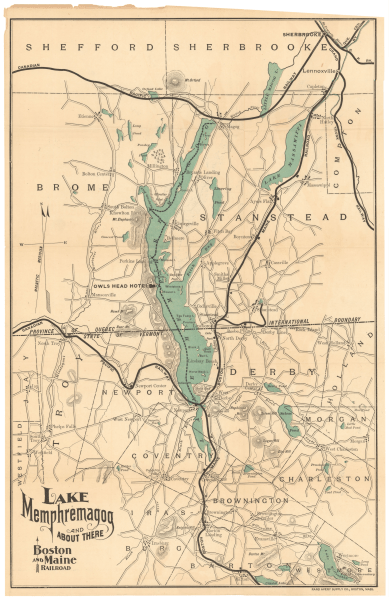

In 1873, when Amy turned eight, her parents bought a huge summer estate property called Woodland on Lake Memphremagog just south of Georgeville, Quebec. Lake Memphremagog1 is in the Eastern Townships just 72 miles east of Montreal, Quebec. It is 31 miles long, from north to south, spanning the international border between Quebec and Vermont but is predominately in Quebec.

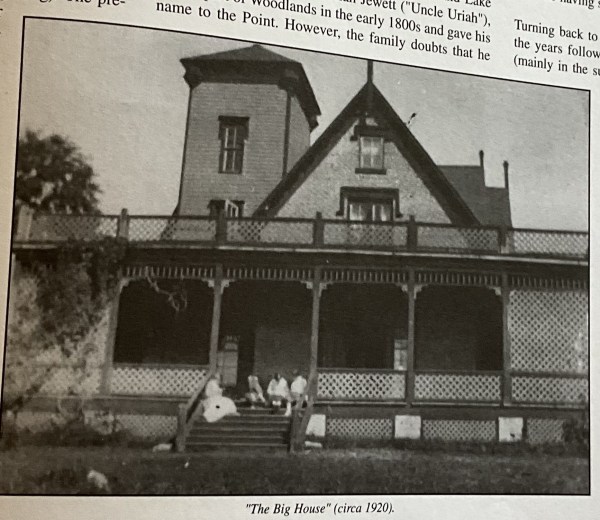

Amy’s father acquired “Woodland” from the original owner William Wood and it consisted of 280 acres of land bordering on the waterfront. William Wood had built a large red brick manor house that a neighbour described as a “barrack with a steeple.” Regardless of how it looked, it became home to several generations of the Lindsay family until the early 1960’s when it was replaced. They affectionately called it “The Big House.”

During this time, several other wealthy English speaking families acquired farm properties in the area and established their summer residences there as well. Woodland became a full functioning farm complete with livestock and crops all managed by hired hands. Over time, various third parties managed the farm until well into the 20th century, which left the family with plenty of free time on their hands.

The Lindsay family took up residence in the Big House every summer. Amy’s father worked as an accountant for the Bank of Montreal and evidently could be spared for the long summer months to enjoy time with his family. “Apparently Robert Lindsay followed a daily routine of walking around the property with his entire family in tow according to size.” On another special occasion the whole family dressed up in fancy costume clothes for a party.

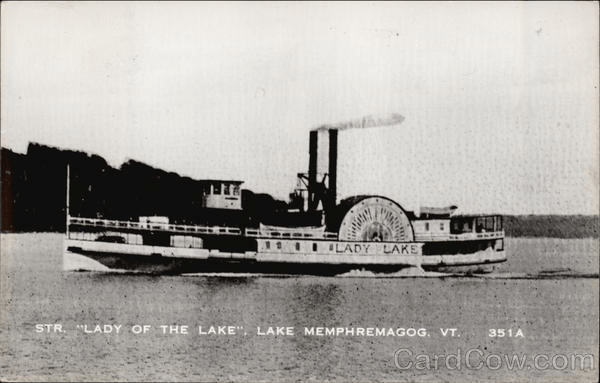

The grand “Lady of the Lake” steamer would sail twice daily on Lake Memphremagog stopping at private docks and thus providing the family with lake excursions right from the front doorstep of the “Big House.”

The Lindsay family (including mother-in-law Vennor who rescued Woodland financially in 1885) enjoyed the property until Robert’s death in 1891. Mrs. Vennor died four years after him and the property devolved to the four surviving grandchildren: Amy, Douglas, Cecil and Edith. (Their brother Sydenham died young while trying to save a drowning victim.)

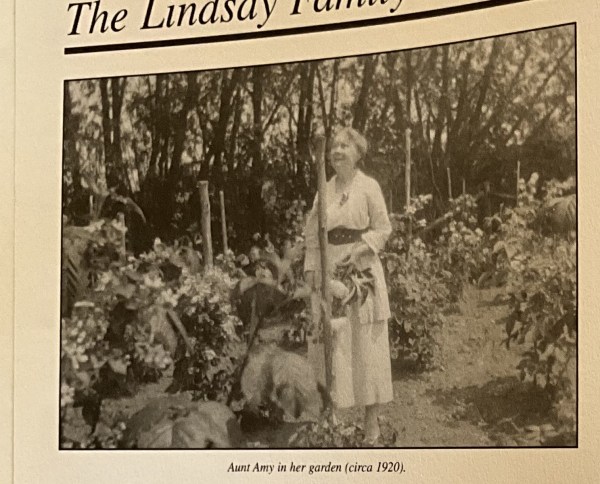

According to her family, “Amy was a small lady, well liked and well respected by most… She loved the lake and Georgeville and spent almost all her summers there… She lived in the Big House and had a beautiful English country garden nearby where she liked to spend many hours puttering about.”2

Although Amy never had children of her own, her many nieces and nephews doted on their “Aunt Amy.” After her mother died in 1913, her nephew took her to Paris and they stayed at the Hotel Pas de Calais, a four-star boutique hotel, right in the heart of tourist Paris. Nothing but the best for Aunt Amy!

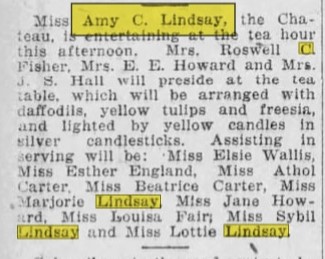

According to an article in the Montreal Star, when Amy hosted a social tea at The Chateau (across from the Ritz-Carlton Hotel), “the tea table was arranged with daffodils, yellow tulips and freesia and lighted by yellow candles in silver candlesticks.” What made it even more special were her five adult nieces assisting her in the serving of tea. She must have been very proud!

Woodland stayed in the Lindsay family until 2020 with several generations enjoying the spectacular property and family legacy. The road leading to their property was aptly named “Chemin Lindsay” and remains so today.

Although Amy spent extended summers with the multi-generational Lindsay family at Woodland, she lived the rest of the year in the downtown area in Montreal known as “The Golden Square Mile.”3 She seemed to move around quite a bit but always within the same area first staying with her mother until her death and then sometimes with her sister Edith (Carter) after that. Although in 1920 she enjoyed “wintering” at the Ritz-Carlton Hotel!

Amy eventually settled for her last 20 years in the Maxwelton Apartments on Sherbrooke Street near McTavish across from the McGill University campus while summering at Woodland until she died in 1960 at age 95.

According to the family, she obtained her first TV late in life and became an avid hockey fan! What a thrill it must have been to watch that first televised hockey game in 1952!

Amy on the Georgeville dock 1955 at age 90

In her last will and testament, written in 1896 when she inherited one quarter of Woodland, she bequeathed “Bob” her cherished set of Waverly books by Sir Walter Scott. He died long before her and, unfortunately, they were not to be found in my dusty old boxes!

1https://wiki2.org/en/Lake_Memphremagog – as referenced 2023-10-18

2The Lindsay Family and Woodlands – “Georgeville 200th”

1901 Lake Memphremagog map” by Rand Avery Supply Co. – Ward Maps. Licensed under Public Domain via Commons – https://wiki2.org/en/File:1901_Lake_Memphremagog_map.png#/media/File:1901_Lake_Memphremagog_map.png

3https://wiki2.org/en/Golden_Square_Mile?wprov=srpw1_0 – as referenced 2023-10-18

Notes:

A map of Grand Trunk Railway route Mtl to Portland, the train appears to have stopped in Sherbrooke:

https://digitalarchive.tpl.ca/objects/353690/map-of-grand-trunk-railway-system-and-connections

Archival photos of Georgeville:

https://www.townshipsarchives.ca/georgeville-quebec

Janice Hamilton’s story about the Baggs in Georgeville:

Summer in Georgeville

In the 1871 census in the United Kingdom, categories of disability were added to the census questions. These categories included the deaf and dumb, blind, imbecile or idiot, and lunatic.1 Imbecile, idiot, and lunatic are pejorative terms today but in the 19th century, they were medical terms used to indicate mental health conditions. Idiots and imbeciles had learning disabilities. Lunacy was a term used broadly to denote anyone with a mental illness.2

James Kinnear Orrock, my 2X great-uncle, was committed to the Dundee Royal Lunatic Asylum on December 9, 1888. Superintendent James Rorie declared that he was a pauper and that he was delusional. James’ mother, Mary Watson, my 2X great-grandmother, requested that he be committed.4 Not unlike today, the police were involved. A constable declared that he had been violent and incoherent. It is obvious from the notice of admissions that James was experiencing psychotic episodes.

James was just 30 when he was admitted to the asylum. Sadly, he remained there until his death in 1930 when he was 72.5 It is distressing that he lived in this institution more than half his life. While little was known about mental illness at the time, the asylum offered the patients safety and hope. Specialist registrar Amy Macaskill states “What is clear is that they wanted to offer a degree of care and protection and containment for people who were causing difficulty at home and were in some level of distress.”6 The asylums cared for people who were depressed, anxious, delusional, as well as those suffering from other conditions such as epilepsy, alcoholism, and syphilis.7

The Dundee Royal Lunatic Asylum had separate quarters for men and women. The pauper wards for men each had a day room, with a number of single rooms with windows overlooking the airing court. The windows provided the only ventilation. The rooms were not heated but there were open fire places in the corridors. There were weaver shops in a separate building where some patients made packing cloth. Male patients also did stone breaking and some worked on the grounds. They were paid with tobacco and beer. There was a billiard room and dancing parties for the patients, attended by both men and women. A chaplain provided services on Sundays.8

When James was admitted, he was certified a pauper lunatic. This certification gave him access to psychiatric care, but it does not necessarily mean that he was a pauper. His admission records indicate that he was a seaman and he could have been gainfully employed. The Board of Governors of the asylums assessed each patient’s finances. If any financial assistance was required, then the patient was declared a pauper. If the patient or their family was assessed as being able to entirely finance their own care, they were classified as private patients. Private patients benefitted from better food, were able to wear their own clothes, and could be discharged if the person paying for their care wanted their discharge. Unfortunately, while a technical and legal label, the term “pauper lunatic” carried a stigma and deterred people from seeking help.9

We have come a long way in our care for those suffering from mental illness since the 19th century. The Lunacy (Scotland) Act 1857 formed mental health law in Scotland from 1857 until 1913. Its purpose was to provide official oversight of mental health institutions and to ensure that they were adequately funded.10

Genealogy Ensemble, ( https://www.genealogyensemble.com) our collaborative blog began almost a decade ago. To this day it is still going strong. Nine ladies and one gentleman participate regularly. We, ladies, write stories about our ancestors, while our friend, Jacques Gagne, compiler and researcher prepares informative databases for posting on our blog.

The ladies meet once a month during the school year to discuss our stories. Over the years as our blog has grown with our published stories, we have come to realize that there are several among us who have common ancestors. Janice Hamilton and Lucy Anglin are cousins, Barb Angus and Sandra McHugh have ancestors in Scotland and Marian Bulford writes about hers in the United Kingdom. Dorothy Nixon, Mary Sutherland, Tracey Arial, and I, along with Jacques Gagne have French Canadian ancestors. Great diversity!

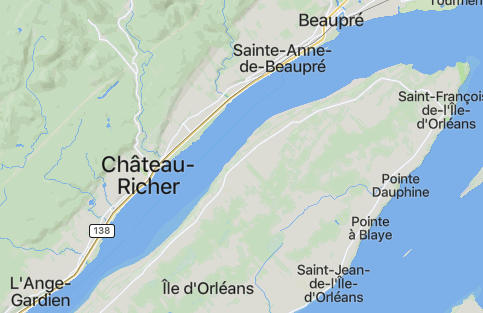

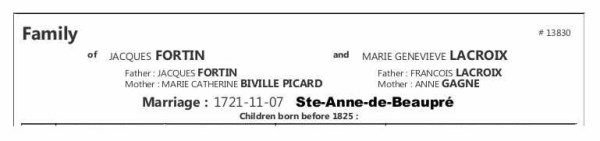

Jacques and I have discussed our ancestors knowing that they came to New France within a few years of each other and settled in the Sainte Anne de Beaupre area.

Initially, being a neophyte writer, and researcher, better skills were required, and completing the branches of our family trees was needed before tackling the relationship between Jacques’ ancestors and mine.

”That time has come”.“

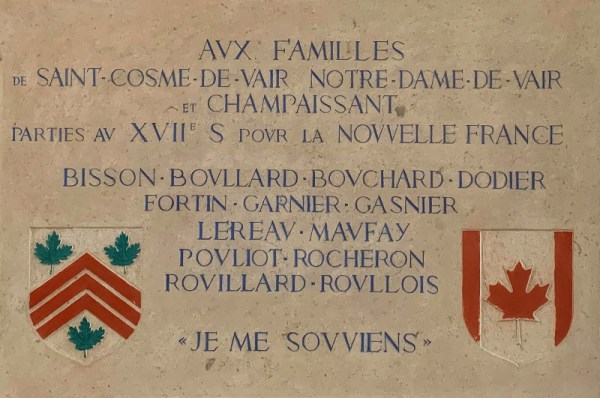

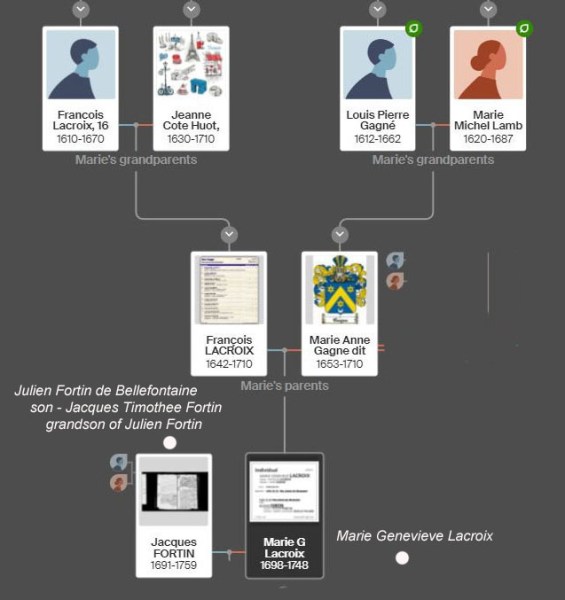

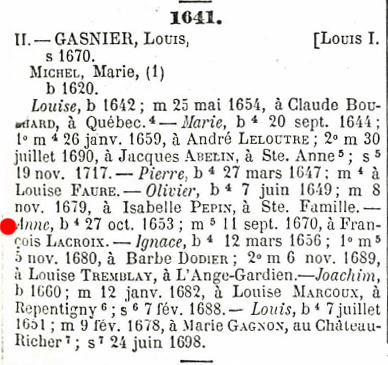

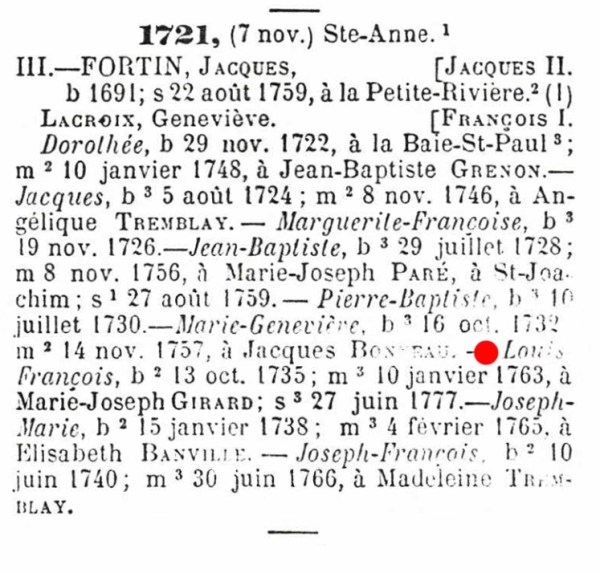

Yes!” We are related going back more than 372 years when Julien Fortin, my 7th great-grandfather, a butcher, who in 1651, followed in the footsteps of Louis Gagne, the baker, Jacques’ great-grandfather who sailed to the New World in 1644 and settled in New France. Both men had occupations that would be welcomed in small communities.

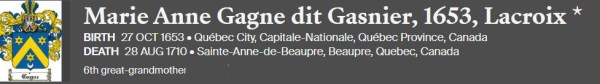

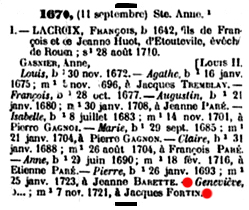

The following graphics and details below tell the story of our ancestors; Jacques’ and mine. I have chosen to use the graphics from my private Ancestry.ca family tree to indicate these connections.

The stories of our 7th Great Grandfathers and their families are intertwined.

Louis Gagné, Marie, Michel, Julien Fortin, Genevieve Gamache, Francois Lacroix, Jeanne Huot, and their son, Francois Normand were born in France.

The others were born when their families arrived in New France.

Louis Gagné married Marie Michel in France and arrived here in 1644.

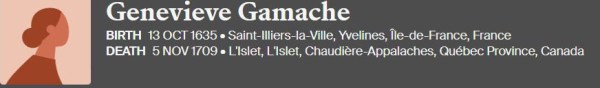

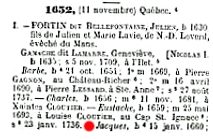

In 1651 Julien Fortin arrived and in 1652, married Geneviève Gamaache “ une fille a marier’ who had arrived with her brother, Nicolas Gamache.

Louis Gagné and Julien Fortin along the way eventually found themselves and their families living around Chateau Richer and Saint Anne de Beaupre, east of Quebec City. Both families owned land along the shore of the St. Lawrence River.

GAGNE

FORTIN

Jacques Fortin is the son of Jacques Timothee Fortin and the grandson of Julien Fortin and Geneviève Gamache.

LACROIX

MARRIAGES

François Lacroix was a “domestique.” Servants working in a home, agricultural servants and personal servants.

Any person at the service of another, without specifics. François Lacroix was employed as a domestic for Pierre Gagnon.

Genevieve Lacroix was the daughter of François Lacroix and Anne Gagné.

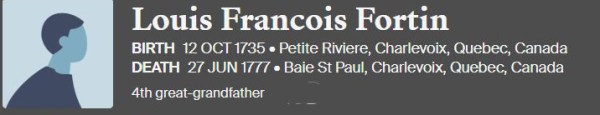

Louis François Fortin is the son of Jacques Fortin and Geneviève Lacroix

Continuing the relationship chart to the Author

François Xavier Fortin – 3rd gg Montebello, Quebec

Moyse Hypolite Fortin – 2nd gg Rigaud, Quebec

François Evariste Fortin – 1st gg Pembroke, Ontario

Louise Seraphina Fortin’s – my grandmother, Louis Joseph Jodouin – my grandfather Sudbury, Ontario

Estelle Anita Lindell – my Mother & Author – Sudbury, Ontario

Sources:

Ancestry.ca – Personal family tree is the source of the research and graphics.

http://www.gagnier.org/p0000353.htm

https://www.genealogiequebec.com/fr/

Notes

Dedicated to our good friend, Jacques Gagné who has recently moved to British Columbia to be near family. He will continue to grace our blog with his databases. We at Genealogy Ensemble wish him well.

Some branches of family trees flourish while others wither and die out. I have traced one branch of my tree back to Pierre Gadois and Louise Mauger, two of my one thousand and twenty four 8th great-grandparents who arrived in Quebec in 1636. This couple has many thousands of descendants alive today, probably even more. But even though some of my great-grandparents had many children there aren’t the expected number of cousins. I have only seven first cousins while a friend says she has more than fifty. My granddaughter has only two so far.

Barnabé Bruneau and Sophie Marie Prudhomme my two-times great-grandparents had 13 children. They all survived to adulthood. One would have expected that they would all marry and have a number of children. Even if they each had only four children, that would be 52 cousins but that is not what happened.

These 13 siblings only had 17 children with 10 of the children born to Ismael Bruneau and Ida Girod. Seven of their ten children have descendants alive today. I haven’t counted up how many relatives this is but quite a number. It is hard to keep track of your second and third cousins and those once removed as they marry and have children.

When my great uncle Herbert Bruneau, Ismael’s son, drew up a family tree in the 1960s, he wasn’t able to find a record of any of his cousin’s children. He thought that he and his sibling’s descendants were the only branches.

When I had my DNA analyzed by Ancestry, one of my matches, “Shedmore” rang a bell. Ancestry said he was a 4th – 6th cousin but in fact, his great-grandmother Elmire Bruneau was my great-grandfather Ismael’s sister and so we are third cousins. The tree did have another branch.

Elmire, born in St-Constant, Quebec, immigrated to the United States in 1864 and worked in New York City as a French governess. She is said to have met Andrew Washington Huntley around 1867 in the choir of the Plymouth Church in Brooklyn Heights. His family lived in Mooers, New York. He was a veteran of the Civil War having served in a number of units from 1862-1865. This couple moved many times during their marriage according to census records. First to Wells, Minnesota, then to Bridport, Vermont to farm, then Chicago, Illinois where he was a ticket agent on the Electric Railroad and finally to Los Angeles, California. Elmire died there in 1922. Her body accompanied by her daughter Faith, went by train back to Bridport, Vermont where she was buried beside her son Howard.

Howard died at 18 without children. It was her daughter Faith, who married Smith C. Shedrick and had four children, Etta Elmere, Howard S., Helena F. and Howard H. who kept the family tree growing. “Shedmore” turned out to be Etta’s son. He does not have any children but his brother had three children, five grandchildren and some great-grandchildren so Elmire’s Bruneau line lives on. Both Helena and Howard also married so there might be even more twigs on those branches.

It is nice to have cousins. Some might not be close but you do have a family connection. Reach out to your cousins, you never know who you will find or what they may know.

Notes:

All photographs are from Ismael Bruneau and Ida Girod’s albums in the possession of the author.

Elmire Huntley Obituary: Middlebury Register, Middlebury Vermont. Dec. 1 1922, Friday page 7. Newspapers.com accessed Mar 29, 2022.

Year: 1870; Census Place: Clark or Wells, Faribault, Minnesota; Roll: T132_3; Page: 1440 Ancestry.com. 1870 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2009. Images reproduced by FamilySearch.Accessed Nov 22, 2021.

Year: 1880; Census Place: Bridport, Addison, Vermont; Roll: 1340; Page: 20A; Enumeration District: 002Ancestry.com and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. 1880 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2010. 1880 U.S. Census Index provided by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints © Copyright 1999 Intellectual Reserve, Inc. Accessed Nov 22, 2021.

Year: 1900; Census Place: Chicago Ward 21, Cook, Illinois; Roll: 271; Page: 17; Enumeration District: 0638 Ancestry.com. 1900 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2004. Accessed Mar 29, 2022.

Year: 1910; Census Place: Oak Park, Cook, Illinois; Roll: T624_239; Page: 21b; Enumeration District: 0077; FHL microfilm: 1374252 Ancestry.com. 1910 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2006. AccessedNov 22, 2021.

Year: 1920; Census Place: Los Angeles Assembly District 73, Los Angeles, California; Roll: T625_114; Page: 17A; Enumeration District: 393 Ancestry.com. 1920 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. Images reproduced by FamilySearch. Accessed Nov 22, 2021.

“Obviously a club does not change from a dump of second hand books to a pan-Malaysia institution without care and attention.” Malaya, 1966. British Malaysia Association. Tribute to Dorothy Nixon, former secretary of the Kuala Lumpur Book

One morning not long ago, I received an email from a young woman in Malaysia. She wanted to know about my grandmother, also Dorothy Nixon, who had been ‘secretary’ of the Kuala Lumpur Book Club back in the day. The woman was a librarian-in-training and she told me that “Granny” was a great inspiration to her.

I wasn’t at all surprised because about ten years earlier I had received a similar email from the former Director of the Malaysian National Library. This illustrious person was researching my grandmother’s life as a retirement project.

It seems that my County Durham born grandmother, Dorothy Forster, who moved to Malaya in 1921 to marry Yorkshireman Robert Nixon1, a rubber planter, is something of a legend in modern Malaysia, at least among librarians.

In 2003, sheer serendipity led me to start my own research into my colonial grandmother. I was a prolific freelance writer back then and it was my habit to enter my name “Dorothy Nixon” into Internet search engines to check out where my essays and articles may have landed.

On this occasion, I stumbled upon a mention of another Dorothy Nixon, my father’s mother. It was on Amazon.co.uk in a review of a book by historian Margaret Shennan about Colonial Malaya “Out in the Midday Sun”. In the book Shennan mentions my grandmother but only once and only in connection with an ugly incident at Changi internment camp during WWII. She gets her name wrong, too: Dorothy Dixon. The reviewer, a Mr. Smith, corrected this typo and described my grandmother as ‘the endlessly helpful secretary of the Kuala Lumpur Book Club.”

I had met Dorothy only once in 1967 at 12 years old when she came to visit us in Montreal. She was cranky and super-critical of all things Canadian – especially of my ‘shrill’ playmates skipping or biking out on our Snowdon area street – and we did not hit it off at all, so you can imagine how confused I was by this description of her.

So, I tracked down Mr. Smith, a former rubber planter. He told me all about the KL Book Club’s subscription arm where book-boxes were assembled and sent out to people holed up in the jungle in their far-away plantations, a service much appreciated during the 1950’s Communist Emergency.

He further described my grandmother as having a fine and nuanced understanding of literature. She always studied the members’ tastes, he said, in order to recommend books to them.

I eventually wrote a story about “Granny” that got published in the Globe and Mail. That’s how the Director knew to contact me. In return for my help this nice lady mailed me an article from the Malaysia Library Review 1952 co-written by my grandmother about history of the KLBC: “The Kuala Lumpur Book Club: A Pioneer.”

The article explains how the Book Club started out as an informal back-room book exchange for Brits and evolved over the decades into a full-fledged government funded community resource, housed in a two story air-conditioned art deco building near the famed Royal Selangor Club in Kuala Lumpur.

Between the wars there were four libraries in Malaya, including the KLBC and the Raffles Library in Singapore. Although these places were set up for Britishers, members were debating whether it was time to allow locals to join, if only government officials.

The newspaper record 2 reveals that my grandmother, who worked at the Book Club from 1937 to 1966, was instrumental in opening up the library to Asians, male and female, especially students. This is likely why she is so admired today in Malaysia.

In the 1930’s and 40’s, the KLBC had a reputation among some Colonials as a light-weight institution that provided low-brow literature to rubber planters’ wives, who were bored to death with servants to do everything and their school-age children away in England.3

Dorothy, who attended a co-educational Quaker school in England, did indeed have many Tamil and Chinese servants at her husband’s Selangor rubber estate, some of whom watched over my father until he was sent away to school in Cumberland at five years old.

She did, indeed, attend many drunken garden parties and polo matches in the 20’s and 30’s – but eventually during the Great Depression she found something more important to do. For a smidge under three decades she worked at the Book Club 7 days a week, 9 am to 7 pm. In the evening she strolled over to the Royal Selangor Club (in the company of her male friend, an eminent lawmaker) where she scored their cricket games!

Today, if you google “Dorothy Nixon” and “Kuala Lumpur Book Club” many many MANY citations will come up from scholars and journalists thanking my grandmother for help researching their books.

These authors are especially grateful for access to her personal collection of Malaysiana. Apparently, my grandmother was an expert in all things Malayan, a real scholar herself who was always invited to Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman’s birthday bashes, and who at mid-20th century repeatedly made the Malaysia Who’s Who.

So, not lazy at all

END

1) Men working in Malayan plantations were encouraged (forced) by their Companies to go home to find a British wife even if they were happy with other arrangements. My grandfather, Robert, found Dorothy Forster, the daughter of an itinerant Primitive Methodist Preacher who had circulated through his hometown of Helmsley, North Yorkshire in 1912-1914. When she arrived in Malaya, late 1921, Dorothy discovered Robert had an Asian ‘mistress’ as they said back then. Upon his marriage, he did not give her up,apparently. (Re: my Aunt Denise.) She got pregnant with my father immediately.

2. The Malaysia Straits Times is online with a database and many articles citing my grandmother, some with photos, most of them in connection with the Cricket. This link to an article, written in 1966, is a tribute to her work as KL Book Club Librarian and in Montreal in 1967 when she visited us she wasted no time in showing it to my mother. She was obviously in search of respect from us. Indeed, judging from her ‘diary’ searching for respect seems to have been her life’s goal.

https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/digitised/article/straitstimes19660514-1.2.105.12

3) British Colonial wives were much looked down up in rubber country, described as undeserving parvenus, women who would be sweeping out a three bedroom cottage back home in Somerset were they not in Malaya lazing in their airy bungalows, waited on hand-and-foot by servants. Yet, these Colonial Wives were given little to do and forbidden to meddle in local affairs in fear they would cause scandal or upset the entrenched hierarchy of the British, Malays, Chinese Tamils. The British believed it was necessary to send their children away to England as soon as possible for schooling and to avoid their contracting a tropical illness. By the time my father’s younger brother was born, he got to go to a British school in Malaya set up in the hills, considered a healthier milieu.

https://www.theglobeandmail.com/life/my-crotchety-grandmother-deciphered/article955859/

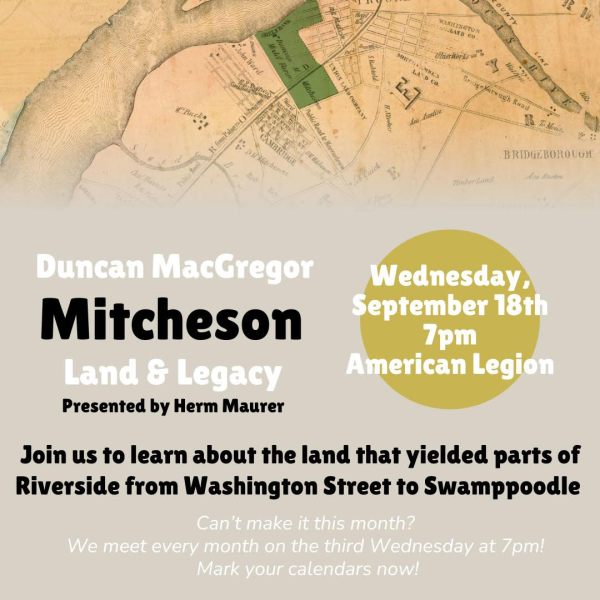

with research from the Riverside Historical Society

updated Nov. 11, 2024

Occasionally someone who knows more about one of my ancestors than I do finds my family history blog and gets in touch. That is what happened this summer when Herman Maurer, a member of the Riverside Historical Society in New Jersey, reached out to tell me that my ancestor had founded his town.

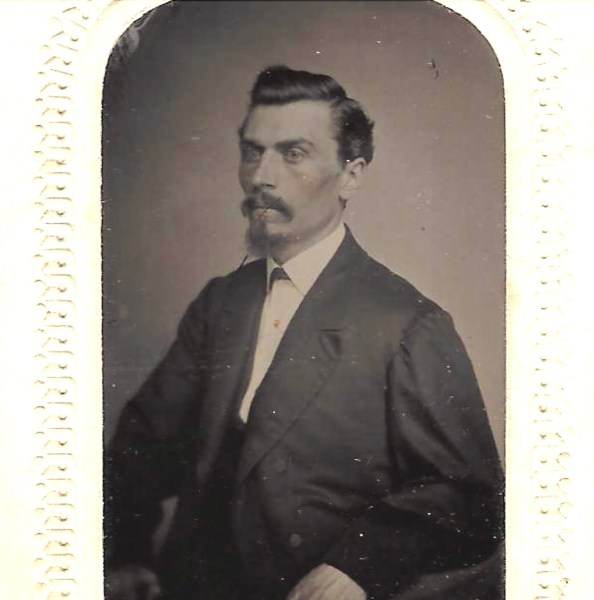

Three years ago, Herman wrote a book called Progress to Riverside: A Story of Our Town’s Past to mark Riverside Township’s 125th anniversary. In the course of his research, he ran across 19th century Philadelphia real estate agent Duncan M. Mitcheson.1

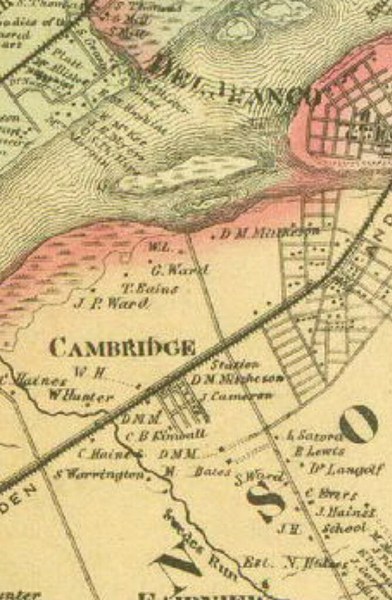

Riverside, New Jersey is a suburban township located across the Delaware River from Philadelphia. In the early 1850s, Duncan and his brother McGregor J. Mitcheson purchased property next to Riverside and subdivided it into cottage lots. This area became the village of Cambridge. Duncan planned the street layout, including today’s busy Chester Avenue, Front Street, Brown, Main and Arch Streets still carry the names that Duncan chose 170 years ago.

Numerous Cambridge deed transfers recorded in the local county clerk’s office between the 1850s and mid-1880s, with the signatures of both Mitcheson brothers on them, convinced Herman that Duncan and his brother McGregor were the primary developers of the village of Cambridge.

This was a surprise to me since I knew very little about Duncan. Now it became clear that he was a successful businessman who embraced modern ideas at a time of rapid changes in society.

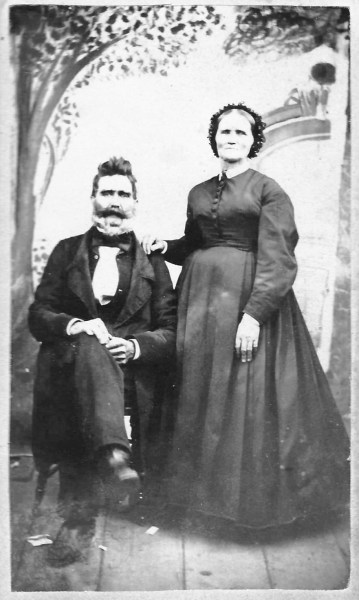

Duncan McGregor Mitcheson (1827-1904) was the middle child of Robert Mitcheson and Mary Frances McGregor. Born in northern England and in Scotland, they were married in Philadelphia around 1818. Duncan’s older sister, Catharine Mitcheson Bagg, was my two-times great-grandmother.

The Mitcheson family lived in Spring Garden, in the northern part of Philadelphia. The family’s home was large and, after their parents died around 1860, Duncan’s older brother, Reverend Robert M. Mitcheson, and his wife and children lived there. Duncan lived with them until Robert died in 1877. In the 1880 census, when he was age 53, Duncan appears to have been staying in a rooming house. Later Philadelphia city directories show that he lived on Spruce Street, near the old part of the city, and had an office nearby on Walnut Street. He never married. Like his two brothers, Duncan attended the University of Pennsylvania, but unlike them, he did not graduate.3 He dropped out in 1842, at the end of his second year. University attendance was rare then: there were only 26 students, all male, in Duncan’s freshman class.

Duncan began his career as a merchant, but an 1861 Pennsylvania business directory identified him as a conveyancer: someone who draws up deeds and leases for property transfers. He was listed as a real estate agent for most of his career.

The Riverside Historical Society’s research revealed that Duncan invested $5000 in land in New Jersey, with an initial purchase of 80 acres, in 1853. He and his brother then formed a real estate partnership to develop the village of Cambridge. An advertisement for these building lots appeared in the Philadelphia newspaper Public Ledger on March 24, 1853. The lots were “located on the Camden and Amboy Railroad, about one mile below Rancocas Creek and the Town of Progress and within a quarter of a mile of the River Delaware, upon a very healthy, dry and level site that will require no filling up, nor grading and can be reached in about half an hour from the Walnut Street Wharf.”

The lots were advertised at the “remarkably low rates” of $25 and $30 each. The $30 lots were 20 feet by 100 feet, while the $25 lots were slightly smaller. A few larger lots were available at $60 and $100 each.

On November 4, 1854, another ad in the Public Ledger noted that the Cambridge lots were near the water, opposite the splendid riverside mansions of Philadelphia’s 23rd Ward. Duncan also reassured potential buyers that the lots were a safe investment. “From the continued increase of the population of Philadelphia, and the consequent increased demand for Houses and Lots, and as well as from the fact that thousands now living in this city could not only have more room, enjoy better health, but live less expensively at Cambridge.”

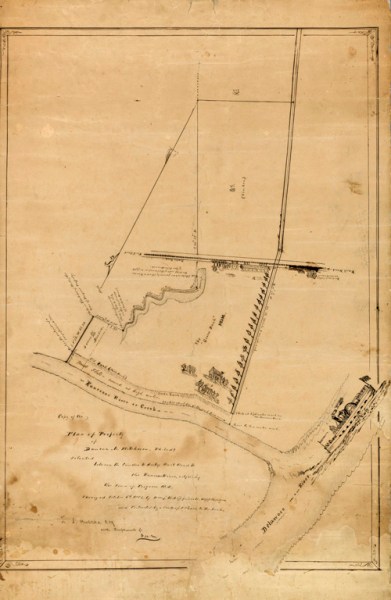

Duncan also owned farmland on three sides of Cambridge, and he was one of the larger landowners in the town of Progress in the 1850s. In January, 1854 he purchased 180 acres of vacant land for $15,000. That property, located between Rancocas Creek, the railroad, Chester Avenue and Tar Kiln Run, was known as Green Bank Farm, or Duncan M. Mitcheson’s Model Farm.

This was a period of technological and scientific innovation. The Great Exhibition, held in London, England in 1851, had showcased developments in many fields, including agriculture. These advances were badly needed: food production had to become more efficient to feed growing urban populations. Duncan’s model farm may have featured agricultural innovations such as a McCormick reaper that could rapidly harvest large quantities of crops. And perhaps Duncan was a member of the Model Farm Association, formed in 1860 to establish a model farm, botanic garden and agricultural school in Pennsylvania.

In the spring of 1854, Duncan purchased another 80 acres of vacant land for $6000, extending Green Bank Farm past the railroad tracks. In addition, he, or possibly his brother, owned a nearby property named Rob Roy Farm, after the famous Scottish outlaw and folk hero Rob Roy McGregor.

How the Mitcheson brothers acquired the funds to buy so much land is not known, but their father owned properties in England and in Philadelphia. Robert Mitcheson senior died in 1859 and in his will, he forgave an $8000 mortgage he held on Duncan’s farm.

In 1859, the Drake Well, the first commercial oil well in the U.S., was drilled in north-western Pennsylvania. That well sparked the first petroleum boom in the United States, creating a wave of investment in drilling, refining and marketing. Duncan saw an opportunity to make money. In February, 1865 he placed the following ad in the Philadelphia Inquirer: “OIL LANDS FOR SALE—located in Venango and Clarion Counties (Pennsylvania). Companies are about to be formed, secure choice lands by addressing or writing to: Duncan M. Mitcheson, real estate office at the northeast corner of Fourth and Walnut Streets, Philadelphia. Also 1,000, 20,000 and 50,000 acres in West Virginia.”

He placed another ad a month later: “CHOICE Oil Tract…Eighty Acres. For sale in fee simple lots situated on the Bennyhoff Creek, Venango County, of which the greater part is boring grounds. This eighty-acre tract will be divided to suit and sold fee simple, with unquestionable titles…”

In July, 1866 Duncan advertised another speculative deal in the Philadelphia Inquirer: 1250 interests, valued at $100 each, in The Virginia Gold Mining Company of Colorado. The company’s property was located near Central City, Colorado, founded in 1859 during the Pike’s Peak Gold Rush.

In 1893, when he was 70 years old, Duncan sold almost 1000 vacant building lots in Cambridge for the sum of one dollar to his deceased brother McGregor’s two grown children, Joseph McGregor Mitcheson and Mary Frances Mitcheson. During the first two decades of the 20th century, they sold many of the Cambridge properties to families who had recently emigrated from Poland.

Joseph, a bachelor, was a Philadelphia lawyer and a commander in the U.S. naval reserve. Mary Frances married accountant Arthur L. Nunns in 1904. The couple were childless and when she died in 1959, at age 84, she gave a million dollars to the Protestant Episcopal Diocese of Pennsylvania. It was the largest bequest it had ever received.4 During my 2013 visit to Philadelphia, the head of St. James School, a tuition-free, private Episcopalian middle school, told me that gift Is still benefiting the community.

As for Duncan, the 1900 census showed that he had retired. He died in 1904 and was buried, along with his parents and other family members, at St. James the Less Episcopal Church Cemetery in Philadelphia.

Note: The images of both maps were provided by the Riverside Historical Society. The Green Bank Farm map was recently conserved through a 2023 grant funded by the Burlington County Board of Commissioners.

See also:

Janice Hamilton, “Robert Mitcheson, Philadelphia Merchant”, Writing Up the Ancestors, March 1, 2023, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2023/03/robert-mitcheson-philadelphia-merchant.html

Janice Hamilton, “The MacGregors: Family History or True Story?” Writing Up the Ancestors, March 21, 2014, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2014/03/the-macgregors-family-legend-or-true.html

Janice Hamilton, “Philadelphia and the Mitcheson Family” Writing Up the Ancestors, Nov. 22, 2013, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2013/11/philadelphia-and-mitcheson-family.html

Sources:

This article is also posted on http://www.writinguptheancestors.ca