When my English-born three-times great-grandfather Robert Mitcheson arrived in Philadelphia from the West Indies in 1817, he was a 38-year-old unattached merchant. Within two years he was married and had started a family, established a new career and was on the way to becoming an American citizen.

Robert (1779-1859) grew up in County Durham, England, where his father was a farmer and small-scale landowner. Robert became an iron manufacturer as a young man, then spent some time in the West Indies. Family stories say he was largely occupied in the West Indies trade. In 1817 he sailed from Antigua to Philadelphia with the intention of settling in the United States. He applied for naturalization – a first step towards citizenship — in July, 18201 and took an oath of citizenship on Sept. 12, 1825.

Perhaps he had met his future wife, Scottish-born Mary Frances (Fanny) MacGregor, on a previous trip to the city. I have not found a record of their marriage, but it probably took place in Philadelphia. The couple’s first child, Robert McGregor Mitcheson, was born on August 15, 1818 and baptized at St. John’s Episcopal Church in north-end Philadelphia.2

In 1819 Robert was listed in a city directory as a distiller, and the following year’s directory clarified that he made brandy and cordials. The business was located at 275 North Third Street, in the Northern Liberties area of the city. The distillery continued to appear in each annual directory until 1835, when Robert was simply listed as “gentleman”, with his home address on Coates Street.

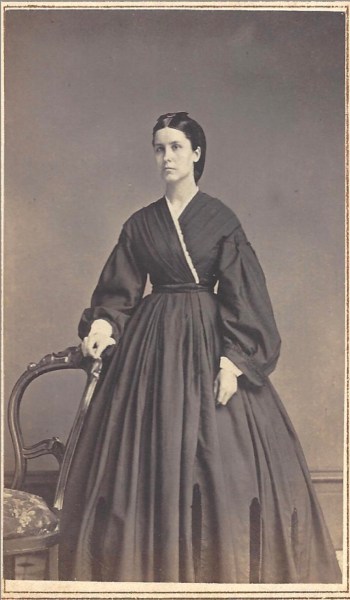

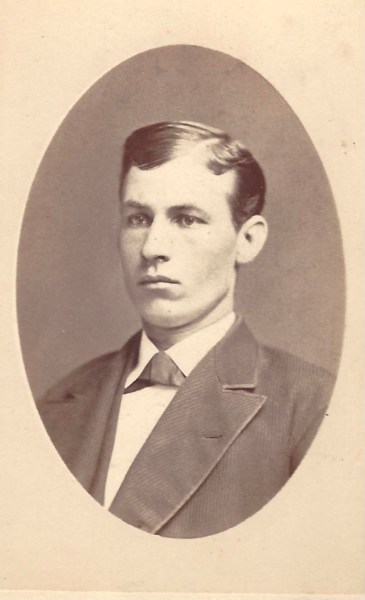

The family appeared in the U.S. census for the first time in 1830,3 living in Spring Garden, then a largely rural part of Philadelphia. Robert owned a large lot bounded by Coates (later renamed Fairmount Street) and Olive Streets, between Eleventh and Twelfth Streets. There, he and Fanny raised their five children: Robert McGregor (1818-1877), Catharine (my two-times great-grandmother, 1822-1914), Duncan (1827-1904), Joseph McGregor (1828-1886) and Mary Frances (1833-1919). Two other children, Sarah and Virginia, died as babies. Two of their sons graduated from the University of Pennsylvania. Robert M. became an Episcopal minister, and Joseph, who went by the name MacGregor J. Mitcheson, was a lawyer.

Robert never became part of city’s elite, despite his financial success. For one thing, he was a newcomer living in an old city. Founded in 1682, Philadelphia was the birthplace of the United States and many of its citizens were known as the descendants of colonial and revolutionary families. Also, Robert appears to have been a low-key person. A search for his name in local newspapers brought up only one article that named a long list of people involved in establishing a refuge for boys.

The only obituary I was able to find appeared in a Montreal newspaper, where daughter Catharine Mitcheson Bagg and her husband, Stanley Clark Bagg, lived.4 It said: “As a citizen of Philadelphia for more than 40 years, he has done much, in a quiet and unostentatious manner, for the advancement of her interests and the relief of the distressed. He enjoyed a well-earned reputation for unwavering integrity in all the transactions of his long life – prolonged almost to his 80th birthday — and his remarkable urbanity of manner which the firm, yet elastic step of his manly person, were but slightly impaired up to the period of his dissolution. He was universally respected and died serenely, with a Christian’s hope and faith.”5

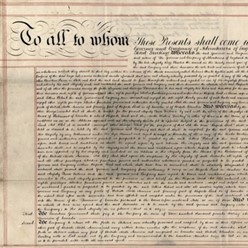

Robert appears to have travelled back to England at least once, probably to visit family members and take care of some business, as he had inherited property in Durham when his father died in 1821. A land transfer document dated September 16, 1835 described him as “Robert Mitcheson, iron manufacturer, late of Swalwell, now of Philadelphia”.6 Several weeks later Robert Mitcheson, gentleman, appeared as a passenger on the Pocahontas, sailing from Liverpool to Philadelphia.7

Perhaps he also visited his brother William, an anchor maker and ship owner in London. A short biography of his son published by the St. Andrews Society in Philadelphia described Robert as a “retired merchant and shipowner,”8 however, I cannot confirm whether Robert owned any ships or perhaps invested in his brother’s business.

After Robert left the distillery business he reinvented himself again, this time as a landlord. The city was rapidly expanding and there was a need for housing. Many people lived in boarding houses and Robert saw rents from boarders as a way to generate income for his grown children after he died. In his will, he left 14 “dwelling houses” located near his house, as well as several nearby other buildings, in trust to sons Robert M. and MacGregor J..9 They were to collect the income and pay certain sums every year to their other three siblings, and to look after repairs to the buildings.

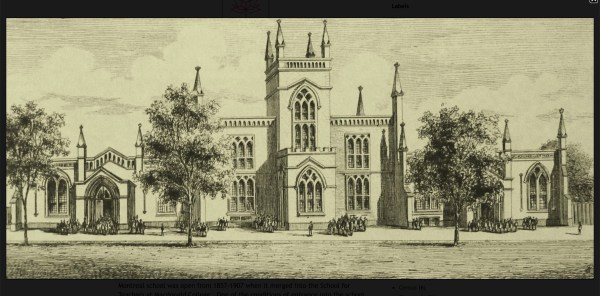

Robert died at age 79 and was buried in the cemetery at St. James the Less, a small, Gothic-style Episcopal church built around 1846 as a chapel of ease for wealthy families in the area. Robert is said to have helped found that church.

His story doesn’t end there, however. Sadly, his estate was the focus of a court battle that took almost 30 years to resolve, by which time both executors had also died. In addition to a dispute between the brothers, the case focused on a legal error in the way the trust was set up10 and who was to inherit the final balance of income.11

To Learn More: Robert Mitcheson’s younger years are the subject of “A Restless Young Man,” Writing Up the Ancestors, Jan. 24, 2023, https://www.writinguptheancestors.ca/2023/01/a-restless-young-man.html. You can also search for articles about Robert’s parents and grandparents in England, his wife, sister Mary and other siblings, and some of his descendants on http://www.writinguptheancestors.ca.

Notes and Sources

1. Ancestry.com. Pennsylvania, U.S., Federal Naturalization Records, 1795-1931 [database on-line]. Original data: Naturalization Records. National Archives at Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Accessed Feb. 15, 2023.

2. I found records from St. John’s Church at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia in 2013.

3. “United States Census, 1830,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:XH5W-MC3, accessed Feb. 16, 2023), Robt Mitchinson, Spring Garden, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States; citing 323, NARA microfilm publication M19, (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.), roll 158; FHL microfilm 20,632.

4. Stanley Clark Bagg (SCB) was Robert’s son-in-law and also his nephew: Robert’s older sister, Mary Mitcheson Clark, was SCB’s maternal grandmother.

5. Montreal Herald and Daily Commercial Gazette, 28 March 1859, p. 2, Bibliothèque et archives nationale du Québec, https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3169230, accessed Feb. 17, 2023.

6. Clayton and Gibson, Ref No. D/CG 7/379, 16 September 1835, Durham County Record Office, https://www.durham.gov.uk/recordoffice.

7. “Pennsylvania, Philadelphia Passenger Lists Index, 1800-1906,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QV9Y-VXJ9, accessed Feb. 17, 2023), Robert Mitcheson, 1835; citing ship Pocahontas, NARA microfilm publication M360 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.); FHL microfilm 419,525.

8. Biography of MacGregor Joseph Mitcheson in An Historical Catalogue of the St. Andrews Society of Philadelphia with Biographical Sketches of Deceased Members, 1749-1907, printed for the Society 1907; p. 287, Google Books, accessed July 19, 2013.

9. Will of Robert Mitcheson, March 5, 1859. Philadelphia County (Pennsylvania) Register of Wills, 1862-1916, Index to wills, 1682-1924. Volume 41, #105, FamilySearch, (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C9B2-5S45-H?i=190&cat=353446, image 191-194, accessed Feb. 18, 2023.)

10. Mitcheson’s Estate, Orphan’s Court. Weekly Notes of Cases Argued and Determined in the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, the County Courts of Philadelphia, and the United States District and Circuit Courts for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania by Members of the Bar. Volume XI, December 1881 to August 1882; p. 240. Philadelphia: Kay and Brother, 1882. Google Books, accessed Feb. 17, 2023.

11. Mitcheson’s Estate, Pennsylvania Court Reports, containing cases decided in the courts of the several counties of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Vol. V, p. 99. Philadelphia, T. & J.W. Johnson & Co., 1888. Google Books, accessed Feb. 17, 2023.

This article is also posted on my family history blog, www.writinguptheancestors.ca