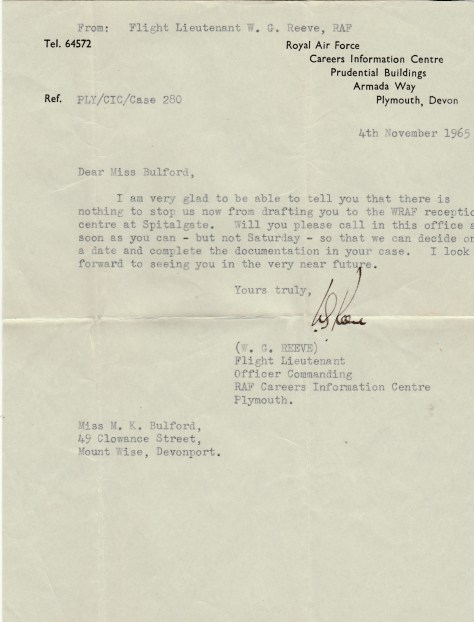

With the following letter, so begins the most exciting period of my life.

It came to a 19 year-year old me still living in Plymouth, Devon England the town of my birth. That version of me wanted something new. Having left school at 15 years and one month hardly qualified me for anything other than low-paid dead-end jobs, until, like most girls around me, marriage beckons. Such was NOT the life I wanted, so I applied to join the Women’s Royal Air Force (WRAF). To my amazement, I got in.

Initially, it seemed a lark and a good way to show off to my friends. Still, joining up offered a chance to leave home with accommodation, a job and an ability to feed myself all at the same time. I had to take the chance!

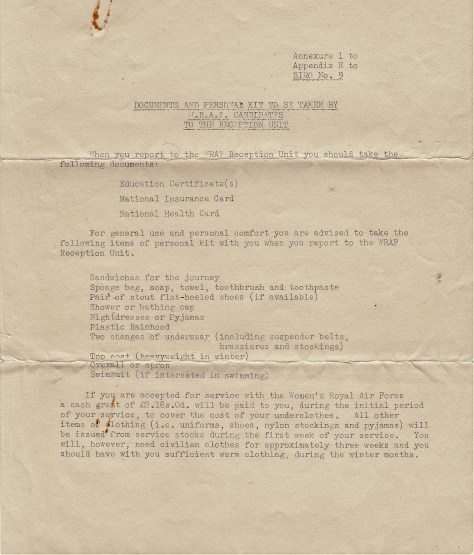

Soon after the initial interview in Plymouth with Flight Lieutenant W. G. Reeve – above – As the letter states, my acceptance was based on passing a medical examination and a selection interview at RAF Spitalgate, In Lincolnshire. To travel there I was issued with travel documents and a kit list including an apron! Stockings! Suspender belt!.

Travel Warrant and Kit List for the journey.

I left my home in Plymouth to Kings Cross railway station in London then a 4 and 3/4 hour journey. From there, another train from Kings Cross to Grantham, Lincolnshire railway station to join several other nervous-looking girls. We discovered a phone on the wall with the first order of our careers. It read:

“RAF SPITALGATE

NEW RECRUITS

PHONE FOR CAR”

Once on ‘camp’, our Corporal introduced herself and we were ushered into a room in a large building known as the barracks. This is where we would sleep and live together, for the next six weeks. It was a vast room with 10 beds either side spaced out with a locker and a wardrobe. Once we had deposited our luggage in our space, the Corporal took us to a cafeteria-like place called a mess for our tea and the food was really good!

The next day the medical assessments began. We had medical exams, Xrays, general fitness tests dental examinations and vaccinations. We started out with about 22 girls which whittled down to 17 after that first day. The next day, those of us who were formally accepted began our training. First, we were taught how to make a bed the RAF way, keep our ‘space’ clean and tidy enough to pass inspections every day.

Our bathrooms and toilets were at the end of the room. For many of us, this was the first experience of hot running water, baths every day plus central heating. After a few days, several of us developed sinus problems. Our bodies were used to cold houses, fires and baths only once a week.

We soon developed a routine. Every Wednesday, we deep cleaned in a tradition called ‘bull night’. We pushed a large heavy flat ‘buffer’ side to side to polish the floors, A cumbersome task but good for the stomach muscles! We finished by putting newspapers on the floors because nobody was allowed to walk on those perfectly polished floors! We wanted everything shiny and bright the next morning at 6 a.m. inspection. Despite the hard work and need to adapt to new realities, we managed to have a lot of fun.

We had parts of our uniforms issued over the next few days, including the laughable ‘passion killer’ knickers. We were each issued three pairs, pale blue, down to the knee and I don’t think anyone wore them at all, except here, for one night only as a giggle. The photo below shows the ‘buffer’ we used to polish the floors to a high gloss. I’m the one holding the dustpan and a cigarette wearing the pale blue ‘passion killers’

For the next 6 weeks, we learned to wear our uniforms properly, tie our ties, make sure hair was off the neck and how to wear our berets and best blue hats. Most importantly, we learned how to salute an officer. That lead to discovering various badges and who to salute and who not to salute.

We were shown the NAAFI (Navy Army Air Force) shop where we were ordered to buy shoe polish, then taught how to clean our shoes to a very high gloss with spit and polish and repeated for hours on end

We learned how to march together, in order. That’s not as easy as it sounds. A few girls began as ‘camel marchers’ They were girls who just could not march at first. They tended to march with the left arm and left leg together, instead of the opposite.

We marched every day, and everywhere from day one, chanting left-right-left-right, halt out loud as we went! Each day we practised marching on the parade ground for one hour, then off to classes.

In class from 9am to 5pm we learned all about the history of the RAF, and the trades available, which uniforms to wear on which occasion (such as ‘fatigues’ and ‘best blue’) and how to keep our ‘kit’ clean. We had hygiene classes informing us how and when to brush our teeth, take a bath and keep ourselves clean. We had Pt classes to keep fit. It was exhausting and exhilarating. The morning after our first bull night, an officer inspected us the next morning with white gloves and ran her fingers along every surface. We had to stand at attention together, whilst she inspected our quarters. The first few weeks everything had to be ‘done over again’ as she ripped out sheets and blankets and shouted at us saying the beds were not made properly. She complained about the dirty surfaces and how dirty the bathrooms were. We could no nothing right those first three weeks. We had no uniforms yet, so every day we marched in ‘civilian’ clothing with just a beret on. We felt silly.

It was a great day when we were eventually issued with our uniforms and full kit.

Our best blue uniforms at last! Me on the left.

After six weeks of basic training came our ‘Passing Out Parade’ and the next day, after our goodbyes, we were all posted to our various trade training camps, but that is another story!