When I discovered that my Great-Uncle, John Hunter died at the age of 20 in either France or Belgium in 1917 during World War I, I assumed that he had died in battle. He was a gunner, which mean that he either served the guns, handled ammunition, or drove the horses. My first thought was that this seemed like a particularly dangerous assignment.1 With further research, I discovered that it was almost inevitable that he would die.

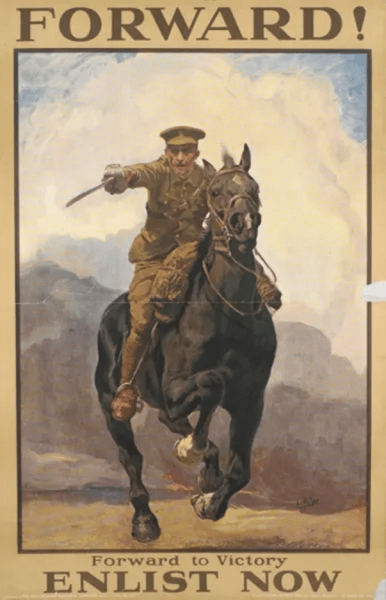

John was assigned to the 87th Brigade of the Royal Field Artillery (RFA). He lived in Fife, Scotland and the RFA was actively recruiting there. In World War I, the minimum age was 19 to sign up, so John would only have seen a year of active fighting before his death. 2 He either enlisted voluntarily or was forced to as the Military Service Act was passed in 1916, requiring the conscription of unmarried and widowed men without any dependents.3

The 87th Brigade was an infantry brigade formation of the British Army. By the time John would have joined the Brigade, it was serving on the Western Front.4 John would have likely participated in the Battle of the Somme and Passchendaele.

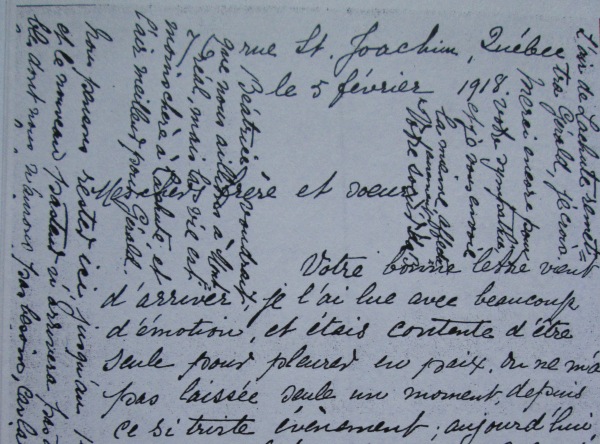

John was taken ill when he was in the theatre of war. He was sent to the Lord Derby War Hospital in Winwick, Borough of Warrington, Chesire, England. He was in a diabetic coma when he died on September 7, 1917, with my grandmother, just 16 years old at the time, at his side. Their mother had died in April 1917 and their father was also serving in World War I and was positioned in France at the time of his son’s death. My grandmother would have been summoned to his bedside and she would have had to make the journey from Lumphinnans, Scotland to Chesire, England by herself.5

Imagine the terror of being diagnosed with diabetes prior to 1921, the year insulin was discovered by a team of doctors, Charles Banting, Charles Best, and J.B. Collip and their supervisor, J.J.R. Macleod, working at the University of Toronto.6 The symptoms would have included a terrible thirst, excessive urination, lethargy, and perhaps confusion. A urine analysis would have been done and a high glucose level would have confirmed diabetes but there was nothing to be done before the discovery of insulin except a strict dietary regime. We now know that diabetes can be triggered by trauma in someone with a genetic predisposition. There Is no doubt that the trauma of trench warfare would have had its toll on John.

When my grandson was diagnosed with diabetes when he was 16 months old, the doctors questioned whether type 1 diabetes was in the family. We could not think of any relative who had type 1 diabetes. We now know that we were wrong. My grandson will live a normal life with the help of a pump that provides insulin as he needs it. But John did not have a chance. He was living through traumatic circumstances, had a genetic predisposition, and life-saving insulin was not yet discovered.

- Wikipedia, Gunner (rank), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gunner_(rank), accessed 17 June 2025

- War Museum, https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/voices-of-the-first-world-war-joining-up, accessed 17 June 2025

- War Museum, https://www.iwm.org.uk/learning/resources/first-world-war-recruitment-posters, accessed 18 June 2025.

- Wikipedia, 87th Brigade, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/87th_Brigade_(United_Kingdom)#:~:text=The%20brigade%20was%20assigned%20to,the%20rest%20of%20the%20war., accessed 17 June 2025.

- Death certificate, John Hynd Hunter, issued 22 April 2025, Grace Hunter, sister, was the informant.

- The Canadian Encyclopedia, The Discovery of Insulin, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/the-discovery-of-insulin, accessed 18 june 2025