Some of the most interesting information about my ancestors comes from documents detailing what they ate.

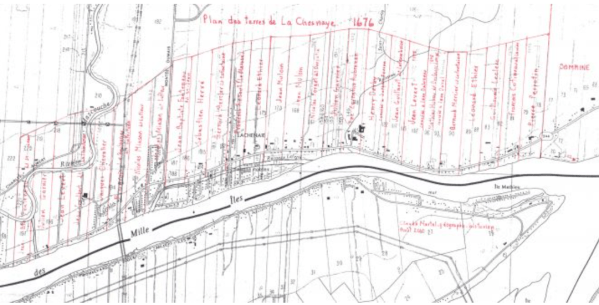

The 1686 Acadian Census, for example, shows my ancestor Alexis Doucet at four years old living in Port Royal with his parents and seven brothers and sisters on “5 arpents of cultivable land with 9 cattle, 10 sheep and eight pigs.”1

The census detailed our ancestors’ cattle and livestock along with the cultivated land because those elements were the primary elements of wealth in North America at that time. The settlers’ ability to nourish themselves determined whether they would be able to thrive, multiple, and permanently inhabit a place on behalf of whichever European colony to which they belonged.

Doucet’s family and their neighbours were ingenious at this task, as Caroline‐Isabelle Caron points out in her delightful booklet about Acadians in Canada.

Indeed, the Acadians set roots in the marshy salines left untouched by the First Nations, in the tidal flood plain which they proceed to dry and put into culture thanks to a complex system of dykes (levées) affixed with drying valves called aboiteaux. This technology was imported from France, probably from the Loudunais region where some early settlers originated. The vast network of dykes the Acadians created inside and beyond the marshlands before 1755, ensured the fertilization of vast meadows for the culture of wheat but also the growth of salt‐hay pastures, a particularly attractive source food for cattle. At this time, Acadian agriculture ranked among the most fertile in the world, boasting near constant, abundant crops.

A typical Acadian farm consisted of one house with one or two rooms on the first floor, a barn, outdoor latrines, a cellar, and a well. Dwellings were usually built up from the ground without foundation, the walls sided with whitewashed cob walls surmounted by a thatched roof. In addition to an enclosure to keep farm animals (chickens, sheep, pigs), the courtyard contained a fenced garden to grow legumes and root vegetables (carrots, turnips, radishes, but not potatoes), herbs (for both cooking and apothecary), and berries. The Acadians planted, among a vast array of fruit trees, the first apple trees the Annapolis valley is reputed for today.

Abundant food supply stimulated strong demographic growth. It is believed that between 1650 and 1755, the growth rate of the population increased annually by 4.5 percent. Birthrates alone explains this growth, the result of a near 100 percent marriage rate and very high fertility rates, as well as low mortality rates due to the quasi absence of epidemic diseases or famine, and easy access to arable land and drinking water. Despite tentative estimates, experts agree that the Acadian population grew from over 400 people in 1671 to more than 1400 in 1730, for a total of 10,000 to 18,000 people in 1755.2

By the way, the dykes made by Acadians like my ancestor, still exist today. The most successful examples allow only a third of the territory to be farmed, with the other two thirds dedicated to natural wetland rejuvenation and rough cover.3

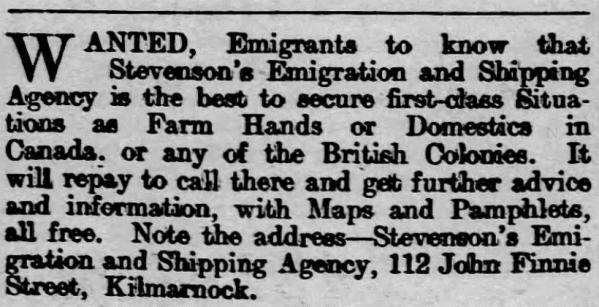

These early settlers’ ingenuity at bringing old world technology to their new circumstances enabled them to cultivate land that wasn’t already being farmed by the First Nations communities already in the area. That fact meant that they weren’t seen as a threat by their First Nations neighbours and became friends and neighbours. Some of the French settlers fell in love with First Nations people, as Alexis’ grandmother had. According to recent DNA research, Germain’s last name “Doucet” is presumed to be an adopted name, because his father, Germain Doucet, definitely descended from First Nations.4

But that’s a tale for another day.

1Hebert, Tim , Transcription of the 1686 Acadian Census, at Port-Royal, Acadie 1686 Census Transcribed. The original census can be found at Acadian Census microfilm C-2572 of the National Archives of Canada “Acadie Recensements 1671 – 1752,” p 30.

2Caron, Caroline‐Isabelle. The Acadians. Immigration and Ethnicity in Canada 33, 2015. http://archive.org/details/the-acadians.

3Fundy Dykelands and Wildlife | Novascotia.Ca.” Accessed February 7, 2024. https://novascotia.ca/natr/wildlife/habitats/dykelands/.

4Estes, Roberta. “Germain Doucet and Haplogroup C3b.” DNAeXplained – Genetic Genealogy, September 18, 2012. https://dna-explained.com/2012/09/18/germain-doucet-and-haplogroup-c3b/.