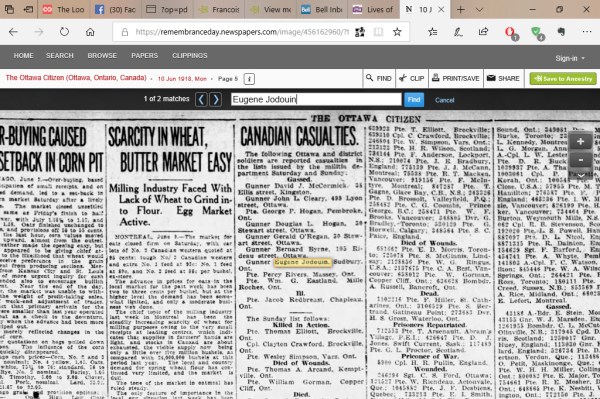

Attestation papers include declarations or oaths military recruits said out loud

Fourteen days after Canada declared War on Italy and the same day France signed an armistice with the country, my grandfather Richard Charles Himphen left his job as a baker’s helper to enlist in The Irish Regiment of Canada.

He said a declaration out loud, in front of someone whose name looks like Mr. Armstrong Cafo, although it might also be Captain M. Armstrong.

…I hereby engage to serve in the Canadian Active Service Force so long as an emergency, ie, war, invasion, riot or insurrection, real or apprehended, exists, and for the period of demobilization after said emergency ceases to exist, and in any event for a period of not less than one year, provided His Majesty should so require my services.”

Then he said:

I Richard Charles Himphen do solemnly promise and swear (or solemnly declare) that I will be faithful and bear true allegiance to His Majesty.”[1]

I know he said those words because they’re on his attestation papers. Although since no one crossed out one or the other I don’t know whether he “solemnly promised and swore” or “solemnly declared.” I suspect he did both because he was reading from the paper and it says both, but I don’t know.

(Note: If you want to read more about Richard Himphen, I have stories about his life here and here.)

Good Stories Need Quotes

Unless you have an ancestor who participated in a court case or worked as an actor, singer or writer, it can be difficult to obtain quotes from his or her life.

Military recruits, however, usually had to say declarations and oaths out loud in front of a witness and both had to sign to make enlistment legal. If that happened, the declarations and oaths will be on their attestation papers.

You also have the name of the witness if you can read his or her signature.

World War II

Most attestation papers include declarations and/or oaths, but not all. The attestation paper of Harry Denis Davy who enlisted in the Royal Canadian Air Force on February 14, 1919 doesn’t include either an attestation or an oath. Then again, it’s possible that there was a third page missing from his service record.[2]

James Fredrick Devitt served with the same unit and his attestation papers included a declaration and oath.

I James Patrick Devitt do solemnly declare that the foregoing particulars are true, and I hereby engage to serve on active service anywhere in Canada, and also beyond Canada and overseas, in the Royal Canadian Air Force for the duration of the present war, and for the period of demobilization thereafter, and in any event for a period of not less than one year, provided His Majesty should so long require my services.”[3]

Soldiers in other wars said different things.

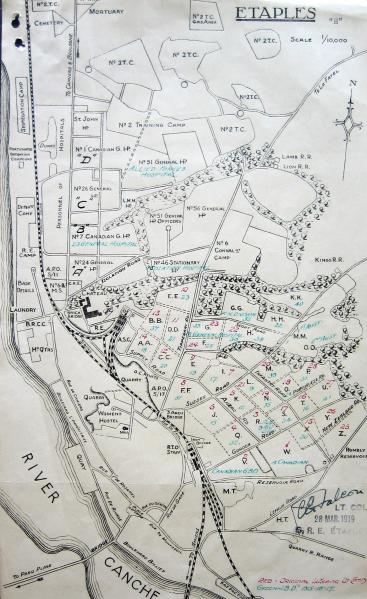

World War I

During WWI, on October 29, 1915, bank clerk John Glass said:

I hereby engage and agree to serve in the Canadian Over-Seas Expeditionary Force, and to be attached to any arm of the service therein, for the term of one year, or during the war now existing between Great Britain and Germany should that war last longer than one year, and for six months after the termination of that war provided His Majesty should so long require my services, or until legally discharged.”

Boilermaker Arthur Luker said the exact same thing on June 24, 1916.

Steamfitter William Wright said the same thing on September 21, 1914.

Henry Hadley Jr.’s file doesn’t include an oath or declaration. He signed a Officers’ Declaration Paper on December 9, 1915 instead.

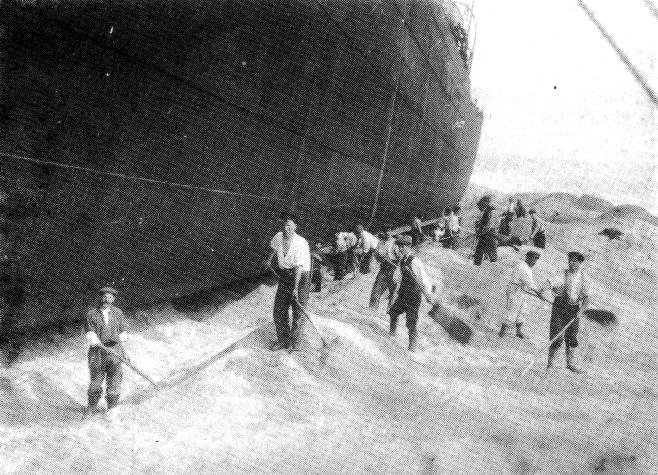

South African War

South African war recruits swore at least two declarations and two oaths. Farmer Henry Smith Munro, for example, swore on October 6, 1899 that he would:

…well and truly serve our Sovereign Lady The Queen in the Canadian Contingent for Active Service, until lawfully discharged, and that I will resist Her Majesty’s enemies, and cause Her Majesty’s peace to be kept on land and at sea, and that I will in all matters appertaining to my service faithfully discharge my duty, according to law. So help me God.[4]

Then, on December 24, 1901, he said:

I Henry Smith Munro, do sincerely promise and swear (or solemnly declare) that I will be faithful and bear true allegiance to His Majesty, King Edward VII, His Heirs and Successors and that I will faithfully defend Him and them in Person, Crown and Dignity, against all enemies and will obey all orders of the Officers set over me.[5]

Abbreviations Can be Tricky

As you go through the form, you definitely want to refer to a Canadian Archives’ abbreviations page to understand everything on the form.

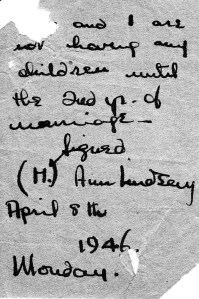

Pay careful attention to marital status. Often, wives or husbands had to send letters to the recruiting office giving permission for someone to enlist. These letters are wonderful sources of direct information about your ancestor.

Also, look carefully for typical fields that remain blank. This might indicate that your ancestor intentionally left the field blank to make sure they would not be rejected. Eliza Richardson describes why nurses left several blanks on their attestation forms during World War I.

The Nursing Sisters who did not fit the camc requirements of age, education, and marital status bypassed regulations by deliberately abstaining from marking down pertinent information on their attestation forms. It is only through pairing Toman’s statistics with the personal accounts of Nursing Sisters in the form of letters, memoirs and photographs that these inconsistencies become clear and a more accurate picture of the composition of the Nursing Sisters becomes possible.”[6]

Look for Historical Context

After collecting information from the attestation papers of your relatives, you may want to do a search of academic papers on Google scholar to figure out how the information you learn fits within common assumptions about historical trends.

Now that attestation papers have been more widely digitized, historians have been examining them for health and sociological information. New interesting papers are constantly appearing.

A simple search informed me about a decades-long discussion questioning why statistics show soldiers at the beginning of World War I being shorter than those who served in the Anglo-Boer War even though there were only 14 years between the beginning of one war and the end of the second.

Last February, Martine Mariotti, Johan Fourie and Kris Inwood from the Australian National University and the universities of Stellenbosch and Guelph came up with a theory to explain the discrepancy in their article Military Technology and Sample Selection Bias.

We posit that new technologies, and the changes in military strategy entailed by those technologies, explain the difference. The Anglo-Boer War, also termed ‘the last gentleman’s war’, was the last war to use cavalry lancers, a military strategy where height is a particular advantage. In contrast, the mechanization of weapons during WWI meant that soldiers’ heights were no longer so important. In this case, improvements to military technology help to explain the apparent decline in stature between the two wars.[7]

If you have an ancestor who served as a soldier in WWI or the Anglo-Boer War, you might want to mark down his height and compare it to the average height of soldiers at that time. Then you can comment on whether he fits the general trend or not. You might also try to figure out whether his task was height-dependent.

Next Steps

If you want help writing stories about your ancestors using attestation papers, I’m offering a course that begins at the end of the month. You can find more information on my Teachable page. There’s also a free course about my four-step system for writing profiles on that same page.

In the meantime, I’d love to hear what you discover about Canadian military attestation papers in the comments.

Sources

[1] Himphen, Richard Charles; Library and Archives Canada, R112, volume 30826.

[2] Davy, Harry; Library and Archives Canada, RG-24, volume 25178.

[3] Devitt, James Frederick; Library and Archives Canada, RG-24, volume 25203.

[4] Munro, Henry Smith; Department of Veterans Affairs fonds, RG38, volume 11170, T-2079, p1.

[5] Munro, Henry Smith; Department of Veterans Affairs fonds, RG38, volume 11170, T-2079, p10.

[6] Richardson, Eliza. “Sister Soldiers of the Great War: The Nurses of the Canadian Army Medical Corps (Book Review)” by Cynthia Toman,” Canadian Military History: Vol. 27 : Iss. 1, Article 9. Available at: http://scholars.wlu.ca/cmh/vol27/iss1/9, accessed January 5, 2019.

[7] Fourie, Johan, Martine Mariotti and Kris Inwood. “Military Technology and Sample Selection Bias,” Stellenbosch Working Paper Series No. WP03/2018, February 2018, https://www.ekon.sun.ac.za/wpapers/2018/wp032018