By

Claire Lindell

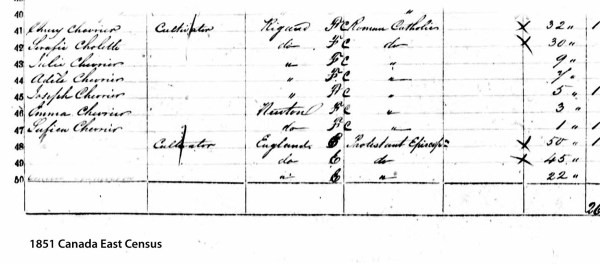

Several years ago, on a pleasant drive home from Ottawa, the thought of stopping in Rigaud to visit the cemetery seemed like a good idea with the hopes of finding Emerie Chevrier, one of my ancestors.

There were so many Chevriers in the cemetery it seemed impossible that one would find Emerie! Every second or third headstone was a Chevrier. It became apparent that more specific information would be required to find the father of my great-grandmother, Marie Philomene Adele Chevrier, one of Emerie’s twenty-one children.

At the age of almost twenty, on the 20th of August 1839, he married young eighteen-year-old, Seraphie Cholet. Together they had fourteen children. One every year! In August of 1852, tragedy stuck and at the age of thirty-one she died, leaving him with a heavy heart, hands full, and a home filled with young children.

Upon Seraphie’s passing, Emerie realized he had a major problem that required immediate attention. How could he tend to his farm and a home with fourteen children and no mother to care for them? One can surmise that the community came forward with a helping hand and introduced him to a new partner. It did not take very long before he was able to find a young woman willing to tackle the overwhelming task of helping him raise his family. She was one Mary McCarragher, almost twenty years old, of Irish descent. She and Emerie, still a young man of thirty-three, were married in the nearby village of Ste Marthe on January 11. 1853, less than six months after the death of his first wife.

Over the years Mary and Emerie had seven more children and he continued to farm the land. The family moved to Ste Justine de Newton, a small village near the Quebec-Ontario border not far from Rigaud.

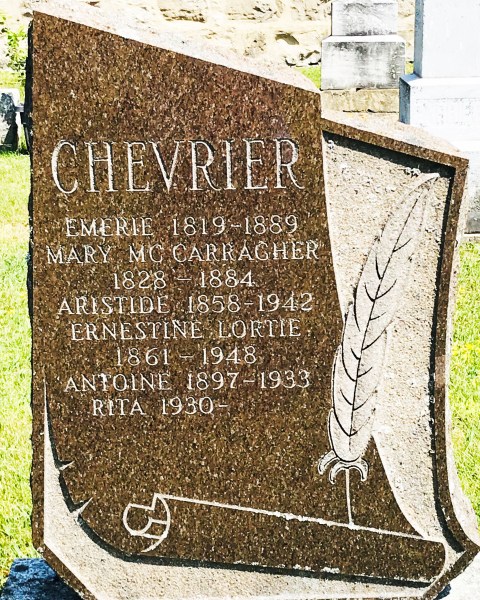

After numerous searches to find information about Emerie’s death. 3 I was able to find his “sepulture”, the French church record of his death indicating where he is buried, a small burial ground, a fraction of the size of the Rigaud cemetery. This was the key to finding Emery. The headstone is situated beside the Catholic Church in Ste-Justine-de-Newton.

Using Google Earth helped to determine the exact location of the cemetery. Armed with the details, with camera battery charged and ready for action, it was time to take a drive to the quaint village sixty kilometres from home.

Arriving in the small community, I parked near the church and walked to the graveyard, opened the gate and began the search. Much to my surprise, the headstone was about six paces to the left, inside the gate!

Although Emerie had passed away in 1889 and his wife Mary in 1884 their headstone was certainly not one that had endured the weather over one hundred years, but rather, it was a beautiful new headstone.4.Indeed, a fine tribute!

Footnotes:

1. https://www.nosorigines.qc.ca/genealogie.aspx

2. Ancestry.com, 1851 Census of Canada East, Canada West, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia (Ancestry.com Operations Inc), Ancestry.com, http://www.Ancestry.com, Year: 1851; Census Place: Rigaud, Vaudreuil County, Canada East (Quebec); Ancestry.com

3. Ancestry.com, Quebec, Canada, Vital and Church Records (Drouin Collection), 1621-1968 (Provo, UT, USA, Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2008), Ancestry.com, http://www.Ancestry.com, Institut Généalogique Drouin; Montreal, Quebec, Canada; Author: Gabriel Drouin, comp

4. Photograph of Emery Chevrier’s headstone taken by the author.

o galvanize her strength. She collected the books from the bankrupt stores and set about running a lending library from her home.

o galvanize her strength. She collected the books from the bankrupt stores and set about running a lending library from her home.