A piece of speculative genealogy fiction

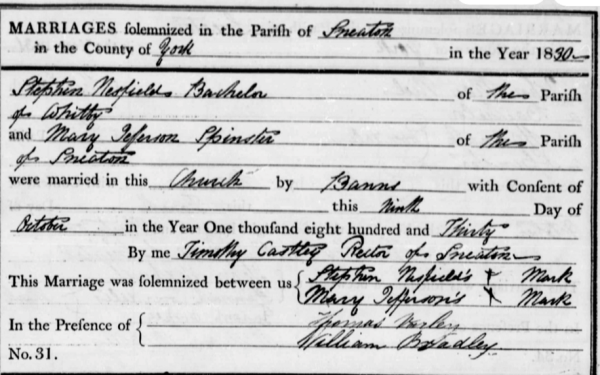

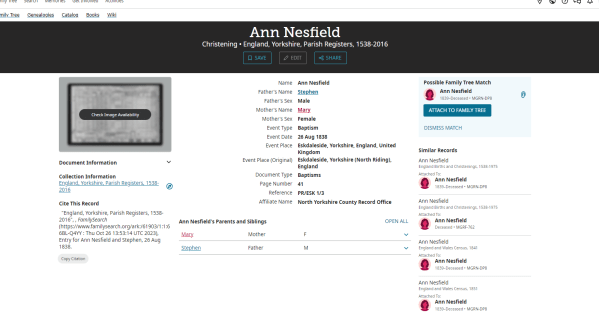

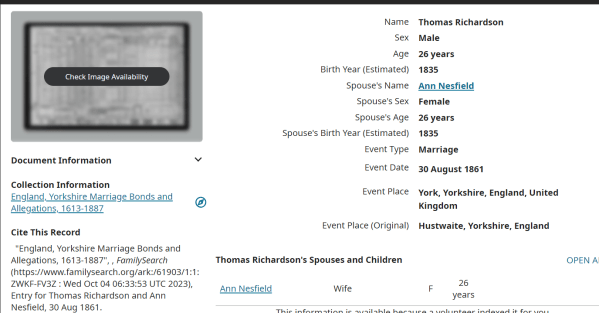

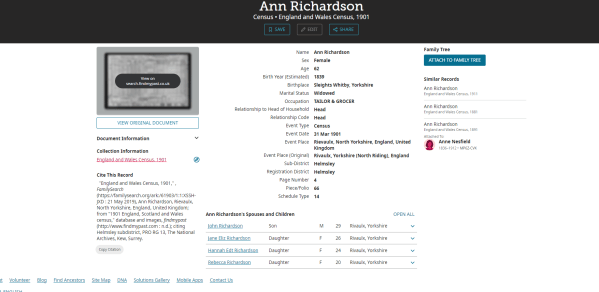

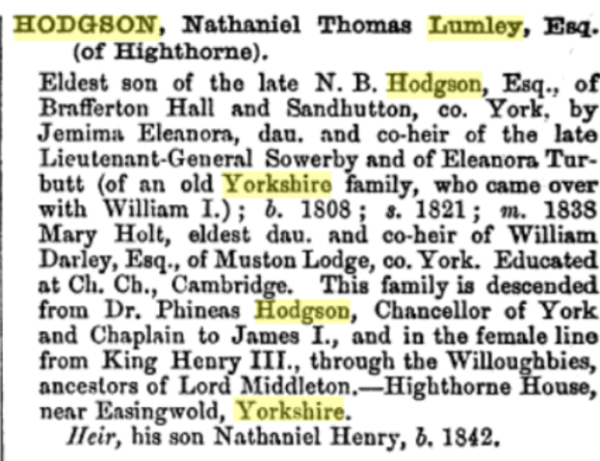

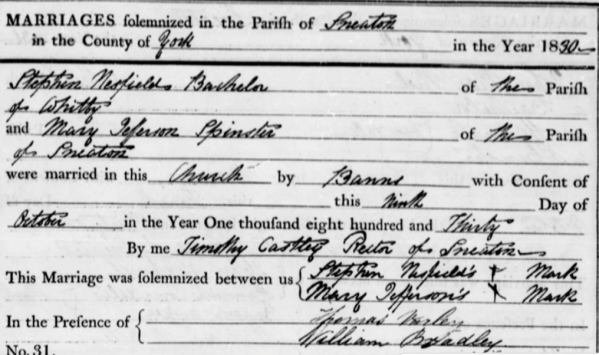

As is typical, I know little about the life of my great great grandmother, Ann Nesfield, a cook from North Yorkshire, UK except the basics: birth (1838), death (1912) marriage (1861) and children (10) but thanks to the Internet I know a great deal about her employer, Nathaniel Thomas Lumley Hodgson, a member of the landed gentry. So, just for fun, I have strung together this little fiction about my great great grandmother from some intriguing facts about Mr. Lumley Hodgson found online.

August 23, 1861. “Happiness in marriage in entirely a matter of chance.” I read that in a book by Miss Austen.

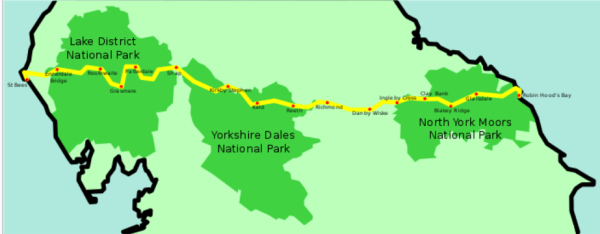

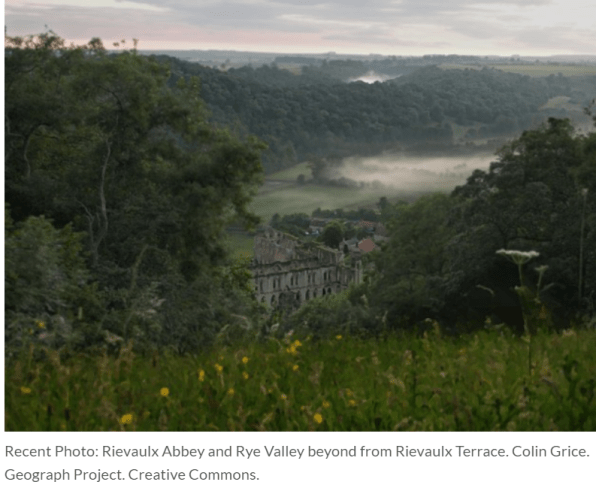

As it happens, I am getting married in less than a week to a tailor from the tiny village of Rievaulx, a man I hardly know, a Mr. Thomas Richardson. He visits my place of employ twice a year in the spring to make up my Master’s riding clothes.

Although most of my Master’s clothing is bought in London, he prefers Mr. Richardson, who lives only 12 miles away, for his country apparel.

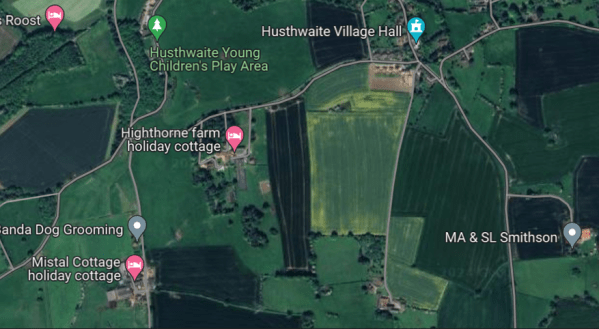

My name is Ann Nesfield. For many years now, I have been engaged as a cook at Mr. Nathaniel Thomas Lumley Hodgsons’ farm estate, Highthorne, near Husthwaite. It is a leisurely employment. I feed his small family, the household staff and the three farmhands. It is rare that important visitors come to stay, and if they do they come on business and sup at the local inn where they can haggle in manly fashion.

You see, Mr. Lumley Hodgson is a breeder of fine horses, of field hunters and of race horses. He trades mostly in the strong reliable Cleveland Bay, a local breed of which he is reet fond.

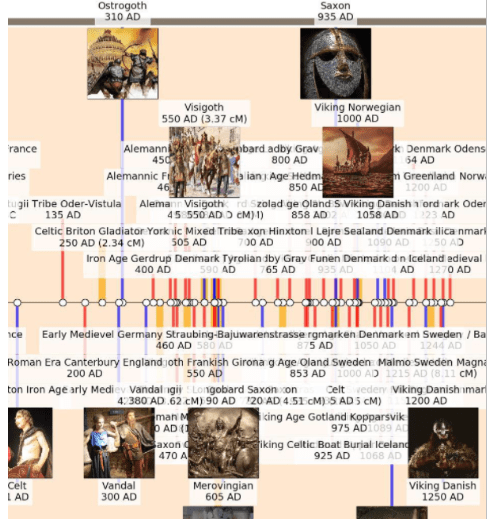

The Cleveland Bay, he informs everyone, was originally bred centuries ago by the local Cisterian Monks as a pack horse. Later, after the dissolution, the Cleveland was bred with some fleet and graceful Turkman stallions.

Today the Cleveland Bay is used in the field, both to hunt and to plow.

Mr. Hodgson seldom fails to tell his customers how 30 years ago he rode his own Cleveland Bay the one hundred and seventy five miles to and from Cambridge where he attended university.

If that doesn’t impress, he then relates the story of how another local man rode his Cleveland mare 70 miles a day for a week for jury duty in Leeds. Or how another man once burdened his beast with 700 pounds and rode 45 miles to Ilkley and back.

“The breed is being ruined,” Mr. L.H. likes to say, “by the London fashion for flashy carriage horses of 16.5 or 17 hands. Leggy useless brutes they are. All action and no go.”

Mr. L.H. calls himself a farmer but he is a gentleman-farmer with a pedigree as impressive as his osses’. At Cambridge he shared lodgings with the great scientist Charles Darwin. This is also summat he usually tells a prospective client, for Mr. L.H. is a canny businessman and this association can only help him, considering his occupation.

There are rows and rows of stables on his 107 acre farm near Husthwaite that sits on one of the seven hills in the area. The main house, they say, was given as a reward many years ago to one of William the Conqueror’s faithful knights.

As I said, my Master’s household is small, made up of his wife Mary Darley (whose family owns many yackers of land in Yorkshire) two daughters, Julia, 22 and Emma, 8, as well as a nurse, a housemaid and a cook, yours truly.

At 23, I have been summat of a sister to Julia, who is sharp-witted but shy in company. She is destined never to marry. At least, there is never any talk of it, not since 1857 and the bachelor’s ball at the Yorkshire Union Hunt Club. So, on fine evenings, I am the one to accompany Julia out riding. We take two bay mares who she says are descended from the Darley Arabian, the daddy of all Thoroughbreds.

I am told I have a better seat than she does, but only by the groom, a Mr. Jack Bell. At breakfast time he likes to call out to me “Mornin’ Milady, grand day i’n’it”- a bit of a jape – and then he laughs showing a great gap where his front teeth should be.

A signed copy of the Voyage of the Beagle lies in a place of honour in Mr. Lumley Hodgson’s private library and has for decades. You can be sure I have never read it, but Julia has and told me all about it. She is the one who had me read Pride and Prejudice. She likes to lend me her favourite novels so she can explain them to me.

Over the years, I have heard (mostly overheard) so much about this Beagle book I feel as if I have read it and even been on the great sea voyage myself to the GA-LA-PA- GOS Islands and seen with my own eyes the strange and colourful creatures there.

Mr. Darwin has lately published another book called, I think, the Origin of Species. A copy arrived by messenger to Highthorne late last year.

This new book of Mr. Darwin’s has caused quite a stir locally. At a Methodist church service a month ago the minister bellowed that Darwin’s theory of evolution is blasphemous. Flippin’ ‘eck! The theory says we all come from monkeys! Mr. Lumley Hodgson – not in attendance – later told the minister that the theories in the book apply only to animals not to humans, but the minister was not satisfied. He said the question of the origin of all species was decided long ago and by an infallible source. He meant the Bible, of course. “God made the animals of the earth after their species as explained by Noah’s Ark.”

So, my Master, who can’t escape this connection with Mr. Darwin now, has decided to quit the farm for a while.

A few days ago he assembled the staff in the south hall and told us he is selling off his best hunters and other stock (including Emma’s comely Cobb pony and his prize Nag stallion) and moving his family to town for the winter. His excuse is that some of his horses have the equine flu (two have already been put down) and he thinks it might be catchin’ to humans.

No matter what the real reason for his takin’ his family to town, the result is that I am left in the lurch with no employment and no place to stay.

But just yesterday, Mrs. L. H. called me into her sitting room, the one with all the paintings of Julia’s frightsome-lookin’ ancestors, and pronounced, “Ann, you must marry Mr. Richardson, the tailor from Rievaulx. He is a respectable man who needs a wife. His sister, who has been housekeeping for him, has suddenly left for abroad. He says he is comfortably settled now in his own cottage and ready to marry and raise a family.”

I must have looked very confused because she continued: “You remember Mr. Richardson from the spring? He waxed ecstatic over your Lamb’s Tail Pie and Tipsy Trifle.” (I did. Seems to me he had eyes for Julia back then.) “He says he needs a wife schooled in numbers to help him keep the accounts. And as Rievaulx is an isolated place, he requires a strong healthy girl who can walk the trails back and forth to Helmsley herself on market day. He is often on the road, so you will not have the use of his carriage as you do here to go to market in Easingwold. Yes, you must marry Mr. Richardson and very soon, too. We can have the ceremony right here in Husthwaite. But first you must visit him in Rievaulx. You can stay at our cousins the Lumleys who have a big farm there.”

So, it is set. My days of making simple Yorkshire meals for a small, ‘appy family in a reet bonnie setting near Husthwaite- and cantering over the dales at darkening with my almost sister Julia – are over.

I am off to Rievaulx to marry and make childer with a stranger. Otherwise, all that is left for me is to flit home to Whitby and that I cannot do. My mother is long dead and my father is in line to finish off his days at the workhouse should none of my half-siblings take him in.

Mr. Lumley Hodgson, his ‘ead filled with other worries, has no objections and no opinions on the subject either, although he jokes, “It’s either Mr. Richardson or Mr. Bell for you, I fear.”

But, I ‘ave watched Mr. Bell as he slips the belly-band around the more skittish horses in his care with a firm but gentle hand, keepin’ his voice soft and melodious all the while and I ‘ave noticed how his muscular shoulders glisten after an honest day’s work and I do not think the joke to be as funny as that.

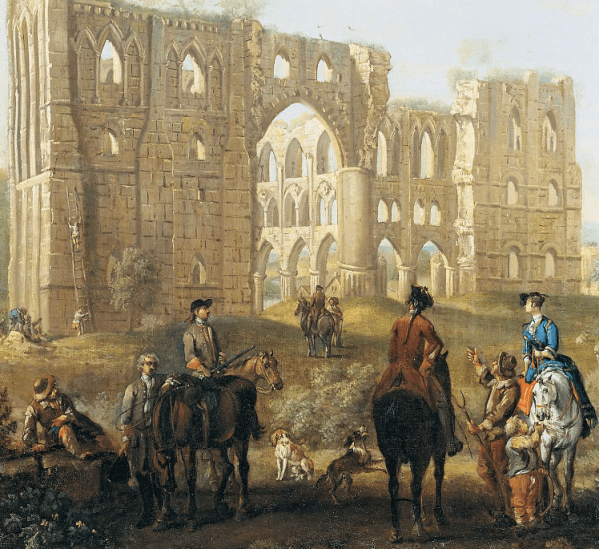

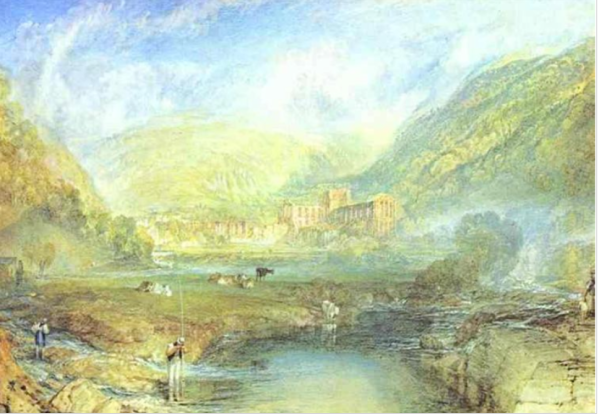

But Jack is a lowly farmhand and Mr. Richardson is a country tailor with a ready clientele and a sweet sunny cottage of his own, Abbot’s Well, with a fine prospect of the Rievaulx Monastery ruins. As I trot along on foot to Helmsley, my poke brimmin’ with dragonwort balm, tansy oil and other home-made potions to sell at market, I can watch from a distance as the Earl of Feversham’s family and friends go a-huntin’ o’er the heathery moors outfitted in all their finery on their own spirited Cleveland Bay/Thoroughbred crosses.

That is the selling point, according to Mrs. Hodgson: The cottage (complete with a little garden for growing my special herbs) and the mannerly profession.

But as Mrs. L. H. was quick to explain, this alliance is a major step up for me. I am but the daughter of a day labourer.

So, I hope Miss Austen is right, that it is ‘best to know as little as possible about the defects of your marriage partner,’ because I know almost nowt about this Mr. Thomas Richardson, except that he enjoys my tipsy trifle. (The trick is to use a lot of high quality whiskey). Still, that is as good a start as any, I reckon.

END

childer: children

Summat: something

Poke: bag

darkening: dusk

reet: very

nowt: nothing

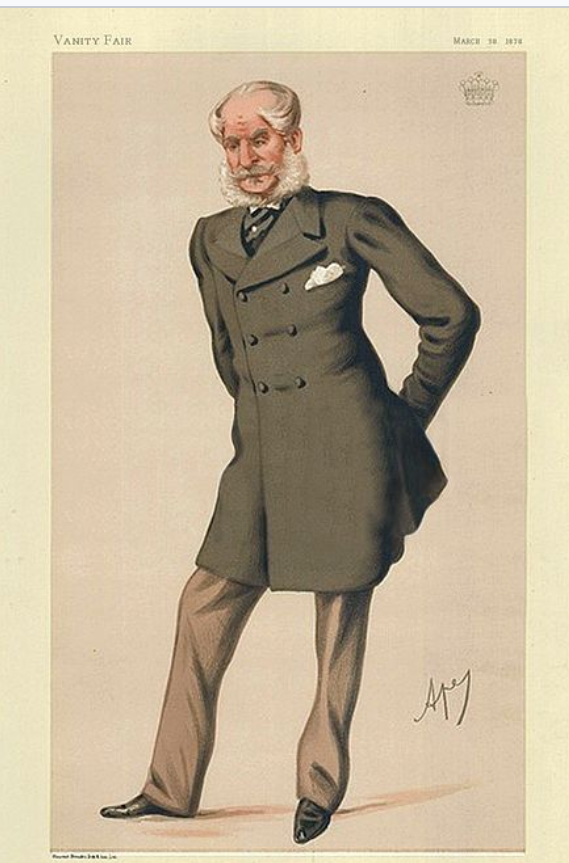

Almost all of the entries for the Lumley-Hodgson’s in the press, mostly Yorkshire press, were related to Mr. L. H.’s businesses, horse and cattle breeding. By the 1870’s he was considered an expert ‘from the old school’ so his curmudgeonly opinions on the ‘horse question’ were much in demand and have left a long paper trail.

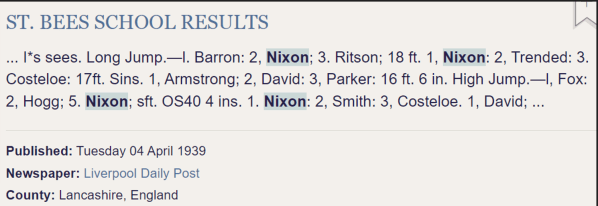

Yes, a notice in the paper in August 1861 said Mr. Lumley Hodgson was leaving Highthorne for ‘the health of his daughters.” (The girls were likely not frail, since Julia lived to a ripe old age and Emma was playing competitive doubles tennis in her thirties, I think.) And, yes, a week later, my great great grandmother, Ann Nesfield got married at Husthwaite.

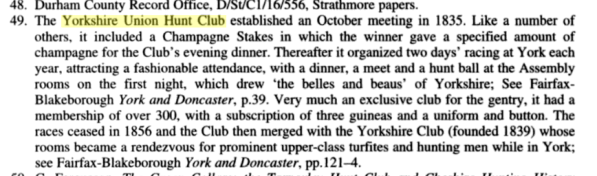

There aren’t many entries in the ‘social notes’ for the ladies of the family despite their good breeding; In 1857, Julia Lumley-Hodgson attended the last? hunt and supper at the Yorkshire Union Hunt Club, (a horse-racing club) where the fashionable young could mingle.

A hunt ball was given in 1867 at Highthorne. And in 1875, Mrs. Lumley Hodgson and Miss Hodgson (likely the much younger Emma) attended a bachelor’s ball in York.

Mr. Lumley-H died in 1886. A notice to creditors was put in the paper, his farm stock, ‘valuable hunters’, and effects put up for auction and his farm “in excellent condition” advertised for let… perfect “for a gentleman fond of rural pursuits.” In 1891 his wife (and girls?) were at Birdsall Manor near Malton (owned by Lord Middleton, a L.H. relation) and Mrs. L.H. was seeking a groom of good character, who must be single to work there. In 1911, her son Captain Hodgson, a widower, was at Birdsall Manor with Julia and Emma, both still single ladies with “private income’ listed where occupation should be.

- A few reports suggest Mrs. Lumley Hodgson dealt in fine art. The portait above was owned by her, found on Archive.org in A History of the Works of Sir Joshua Reynolds, Getty Museum publication. The weirdest entry about Lumley-Hodgson was that as an infant he sued his mother, Jemima, for land. Another online entry about Highthorne says he leased it in 1815. He would have been seven!

The Darley Arabian was brought to England from the East by the Alton, Yorkshire branch of Darley’s. Mary was from the Muston Lodge branch. They come from the same family originally.