When Robert left Ireland for Canada in 1829, young William Anglin (my great-great-grandfather) missed his older brother terribly. For the next 14 years, he wrote letters frequently as the only way to keep him close to his heart. Upon hearing of the rebellions in 1838 in Upper Canada and near Kingston, Ontario, where Robert had settled with his family, William wrote a worried letter:

Another reason why I have not written is the very disturbed state of your country – you cannot think the feelings of my mind on account of you my dear brothers and family for fear you should suffer loss of property, or life. I pray that you may receive this and that it will find you all well. I was afraid that a letter may not pass from here to you, and was kept in awful suspense to know how it would terminate – and anxiously waiting for every account – and you cannot imagine what joy it gave me to hear that the Rebels are in a great measure defeated. ..… I was glad to know from the papers that they did not get up to Kingston, and I hope that you in that city do still enjoy peace. We were glad to hear the stand the Protestants have made with the Army against them. Things may be worse than we know with you but do hope our next account will bring us satisfactory news. A good deal of the Army sailed from England and Ireland for America and do hope they have safely arrived before this date. I forbear to say any more on this, to me, painful subject, and know that you are better acquainted with it than I can be. I only mention what I have said to let you know what I have heard about the agitated state of your country. Under such circumstances as these I hope you will write as soon as you receive this, for I long to hear from you or to see you.

– Excerpt from a letter from William to his brother Robert in Kingston – Feb 23, 1838

In 1843, William at age 28, arrived in Kingston, Ontario, where he finally joined two of his older brothers, Robert and Samuel, in business. William, the youngest of four brothers and one sister, was born in 1815 in Bandon, County Cork, Ireland. He hadn’t seen his brother Robert in 14 years.

Before long William branched out into business for himself, partnering with an iron-gray pony named ‘Fanny’. He travelled along the Rideau Canal as far north as Big Rideau Lake, and also along Lake Ontario to Hay Bay near Adolphustown, purchasing cordwood as fuel for the mail boats operating between Toronto and Montreal – steamers named ‘Passport’, ‘Spartan’, ‘Corsican’, ‘Corinthian’, and ‘Algerian’[1].

Later he purchased his own powerful tug, named ‘Grenville’, as well as two barges and continued to manage the cordwood contract with his young son’s help. The cordwood was then freighted up on scows and barges, and piled on the Long Wharf in Kingston, later known as Swift’s Wharf.[2]

In 1847, four years after his arrival in Kingston, William married Mary Gardiner who had been born in County Durham, England, in 1817, and had also immigrated to the Kingston area with her family.

William and his wife first had two daughters, Mary Frances, who died shortly after her birth in 1850, and Annabella ‘Annie’ Jane.

Annie was born in 1853. Sadly, on July 1, 1878, while watching a fireworks display in the Cricket Field from the roof of a neighbors’ house, she took ill and developed pulmonary tuberculosis. She was only 26 years old when she died on April 18, 1879.[3]

Then came two sons, William Gardiner Anglin (my great-grandfather), in 1856, and James Vickers Anglin, in 1860. They grew up in the house at 56 Earl Street where they moved as young boys with their parents in 1865.

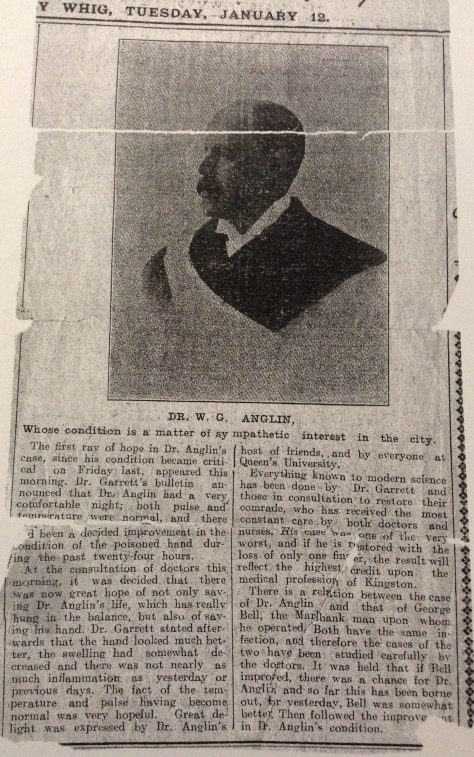

Both sons eventually studied medicine at Queen’s University and became well respected surgeons in Kingston. William, however, also built an extension on his father’s house at 56 Earl Street which served both as his own home and medical office. To this day, the name “Dr. W.G. Anglin” is still etched on the window at 56 Earl Street.[4]

When William’s mother died in Ireland, in 1863, twenty years after William’s arrival in Kingston, his eldest brother, John, was finally able to move to Upper Canada to join the rest of the family.

The Anglin brothers were re-united once again.

[1] http://www.Images.maritimehistoryofthegreatlakes.ca

[2] The Anglin Family Story – Part 2 – www.billanglin.com

[3] The Anglin Family Story – Part 2 – www.billanglin.com

[4] Helen Finlay, owner-operator of 52 Earl Street Cottages, Kingston, Ontario

He served as a civil-surgeon with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel until 1916 when he became ill with Malta fever and phlebitis. He was given a medical discharge and sent back home.

He served as a civil-surgeon with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel until 1916 when he became ill with Malta fever and phlebitis. He was given a medical discharge and sent back home. The story told was that by using his “thought-reading” skills, he was able to physically draw down the infection in his right arm to his middle finger. The amputation of that one finger removed all traces of infection from his body probably saving his life… and enabling him to continue his work as a surgeon.

The story told was that by using his “thought-reading” skills, he was able to physically draw down the infection in his right arm to his middle finger. The amputation of that one finger removed all traces of infection from his body probably saving his life… and enabling him to continue his work as a surgeon.