This post is an update from an earlier version. In the attached 161-page research guide to the seigneuries, notaries and cemeteries of Montreal, I have enlarged the content of the notaries.

Here is the link to the updated compilation (as a PDF): Seigneuries Region of Montréal rev

If you had ancestors in Quebec before 1854, chances are they lived on a seigneury. The seigneur (the owner of the seigneury) granted the land to tenants, who were usually called habitants or censitaires. The seigneurs and the habitants owed certain obligations to each other. The system, based on a feudal one, dates back to the mid-1600s when the government of France was trying to ensure its colony of New France would be settled in a systematic manner.

Seigneurs were usually people of noble backgrounds, military leaders or civil administrators, or they were religious institutions. Some seigneuries were well run, other seigneurs were absentee landlords or excessively demanding. In 1854, the seigneurial system was abolished and the tenants were allowed to acquire the land they farmed. The seigneuries had a lasting impact on Quebec society and geography and the names of many seigneuries and seigneurs live on in the names of towns and streets.

In the days of New France, Montreal was a small city on the shores of the St. Lawrence and the rest of the Island of Montreal was rural farmland. For many years, the priests of Saint Sulpice were the seigneurs of most of the island. The seigneurial system began to disappear from the Montreal region before it did elsewhere because it held back development of the growing city.

The compilation in the attached PDF includes links to a variety of articles related to seigneuries and seigneurs who lived in the Montreal region, both on and off the island. Some articles are in English, others are in French. If you cannot understand the French, copy and paste the text into a translation app such as Google Translate. Included in the compilation are links to articles from the Dictionary of Canadian Biography about some of the leading figures in the history of Montreal, as well as background information about the seigneuries, Catholic parish churches and cemeteries in the region.

This compilation provides links to information on the many seigneuries, fiefs, arrière-fiefs on the island of Montreal and in nearby areas. Various historians work have described these fiefs under different names. For example, from various sources in the City of Saint-Laurent in 1720, the following seigneuries and fiefs were named: Seigneurie Saint-Laurent, Côte Saint-Laurent, Côte Notre-Dame-des-Vertus , Notre-Dame-de-Liesse and Côte-du-Bois-Franc.

In 1854, the Assemblée nationale in Québec issued a decree which halted new seigneuries from being created in the province. However, in order to satisfy the concerns of many of the existing seigneurs, the censitaires, or tenants, continued to pay rents on an annual basis. Finally, in 1935, the Assemblée nationale du Québec issued a new law. The first URL address on the attached research guide links to the rent abolition act which facilitated the freeing of all lands from constituted rents. From 1854 to 1901, the government of Québec issued payments to large land owners (seigneurs). These payments were referred to as Créanciers de rentes.

Up to 1935, notaries were involved in the creation of new documents addressing lands. This is the main reason I have extended the content of this compilation: to include notaries during this late period of time.

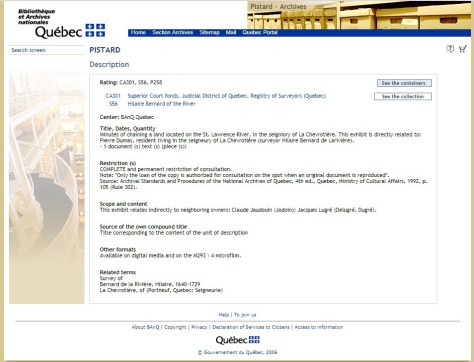

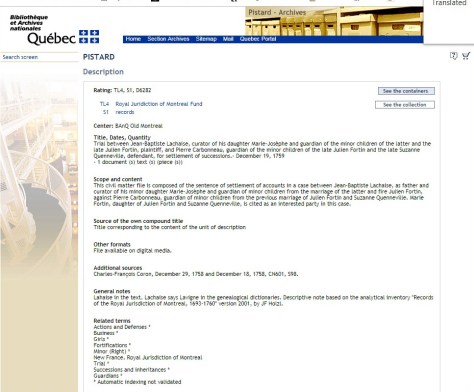

The largest portion of this revised research guide refers to notaries. In this update, I verify the notaries whose dossiers were digitized and are available on the Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (BAnQ) database of notaries http://binnum2.banq.qc.ca/bna/notaires/. Additional notarial acts can be found online on Ancestry.com, FamilySearch.org and Généalogie Québec (Drouin Institute).

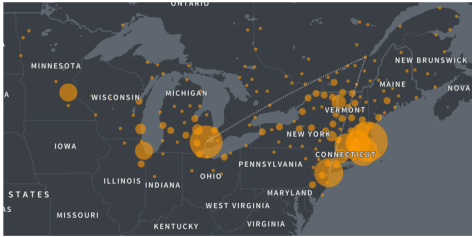

In the regions served by the BAnQ Gaspé, BAnQ Gatineau, BAnQ Rimouski, BAnQ Rouyn-Noranda, BAnQ Saguenay, BAnQ Sept-Îles, BAnQ Sherbrooke, BAnQ Trois-Rivières, about 70% to 80% of the acts written by local and regional notaries can be accessed online at BAnQ, Ancestry, FamilySearch and/or Drouin online.

The BAnQ Montréal and BAnQ Québec (City) are the two largest repositories of the Archives nationales du Québec, and they get the most visitors. With regard to notarial acts being accessible through the BAnQ online database, probably only 40 percent of the notaries who served within the judicial districts of these two cities have had their files digitized as of 2018.

Furthermore, I have noticed over the years that the BAnQ Montréal and BAnQ Québec have not included many of the Royal Notaries (Notaires royaux), either under the French Regime of Nouvelle-France or under British military rule prior to the Lower Canada period of 1791, in the BAnQ database. However, some of the acts of Royal Notaries in the Montreal and Quebec City Judicial Districts, can be found on Ancestry.com and FamilySearch.org. Other notaries can simply not be found online at all.

Here is an overview of the contents of this research guide:

p. 1 Seigneurs, governors, religious and civic leaders of Montreal

p. 7 Seigneuries of the Montreal region, including those owned by religious orders. The seigneuries include Lachine, Riviere des Prairies, St. Anne de Bellevue, Ahuntsic, St. Leonard, Chateauguay, Boucherville, St. Rose, Longueuil, Ste. Therese, Mille-Iles, Vaudeuil.

p. 7 Regional cemeteries

p. 45 Notaries who worked in the area from the beginning of settlement until 1954, and where to locate their acts.

p. 157 Repositories for archival material and other resources, such as books and databases.

p. 159 Authors and online historical resources.