The old notebook has a scuffed brown cover, but its pages are full of poetry, transcribed in neat handwriting. Clearly, this notebook once belonged to a woman who admired Lord Byron and other early 19th century English poets. Her name was Frances – or Fanny – McGregor, and she may have been my ancestor.

I came across it while searching for the name McGregor in the online catalogue of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. The first result to pop up was “Frances McGregor autograph book, 1825.” In response to my query, the society forwarded a digitized copy of the entire notebook.

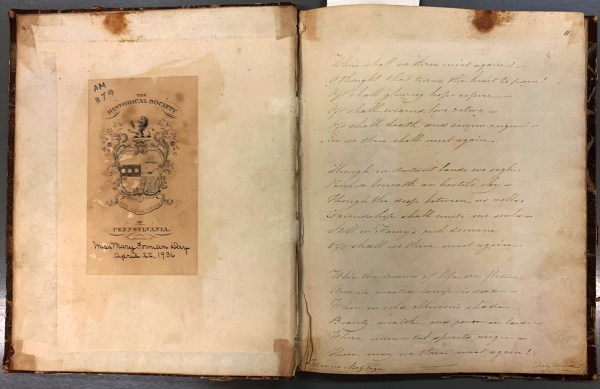

There’s a note clipped to the front, “Frances McGregor? selections from English poets,” which is a more accurate description of it. The label inside the cover indicates it was given to the historical society by “Miss Mary Forman Day, April 22, 1936,” more than 100 years after the last entry was made in 1829.

Who was Mary Forman Day? She could have been a friend of one of Fanny’s grandchildren.1 Born in Philadelphia in 1860, and died in 1950 in Washington, D.C., she was probably the person who gave many documents pertaining to her Forman ancestors — early Maryland settlers — to area historical societies.2

As for my three-times great-grandmother Mary Frances McGregor, she was born near Port of Menteith, Perthshire, Scotland around 1792. She usually went by her nickname, Fanny. According to family lore, she finished her education in Edinburgh and then came to America. She married English-born Philadelphia merchant Robert Mitcheson, and the census shows they lived in the Spring Garden district, on the outskirts of Philadelpia. I am descended from her eldest daughter, Catharine, who was born in 1822.

I tried to eliminate the possibility that another Frances McGregor owned this notebook, but that proved difficult. Only the head of the household was named in census records and city directories at that time, making women especially hard to find.

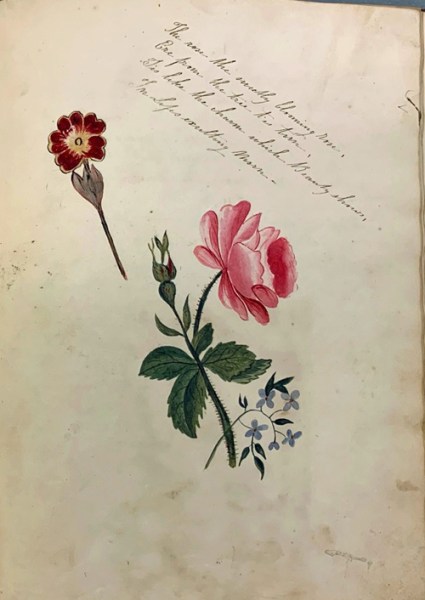

If a title page ever existed, someone tore it out long ago, and the notebook begins on page 11. Nevertheless, Frances’s name appears three times: she signed “Fanny” on a small botanical painting on the last page, and she wrote “Frances” on the inside back cover.

Her name also appears on page 11, at the bottom of a poem that begins, “When shall we three meet again?” Those words were spoken by the three witches in Shakespeare’s Macbeth, but this is a different poem, expressing the sadness of friends about to be parted. Perhaps Fanny included this poem because she knew she would be leaving her life in Scotland for a new one in the United States.

Many of the poems Frances included in the notebook were written by Lord Byron. She also included a passage from Milton’s Paradise Lost, a short excerpt from an opera and “A Canadian Boat Song, written on the River St. Lawrence”, written by Irish poet Thomas Moore and first published in 1805. The notebook ends with several poems about England’s Princess Charlotte. In 1817, her baby was stillborn and the princess also died. These tragic events inspired much public sympathy at the time.

Frances seems to have written at least one of the notebook’s entries herself. “A Poem – On Home, written by a Young lady at School in the Year 1814” described memories of a loving mother and a happy childhood, but complained of loneliness and disillusionment as the young author moved toward adulthood.

Besides poetry, Frances included several “puzzles” such as, “Why are your eyes like coach horses?” and “Why is a washerwoman like a church bell?” and “How is a lady of loquacity like a lady of veracity?” She did not include the answers.

My other favourite entries are the botanical paintings: simple but colourful images of wild geraniums, wild violets and roses.

Whoever created this notebook, it is clear that she was well educated, probably from the upper middle class, and had a quirky sense of humour. The more I think about it, the more strongly I suspect it belonged to my Frances McGregor, but I can’t prove it.

Photo credits: “Frances McGregor autograph book, 1825,” courtesy the Historical Society of Pennsylvania

Notes

1. Grandchildren of Fanny McGregor Mitcheson who could have known Mary Forman:

Joseph McGregor Mitcheson (1870-1926) WW1 navy officer and Philadelphia lawyer;

Mary Frances (Mitcheson) Nunns (1874-1959);

Robert S. J. Mitcheson (1862-1931) Philadelphia physician and art collector;

Helen Patience Mitcheson (1854-1885);

Fanny Mary (Mitcheson) Smith (1851-1937) wife of Philadelphia lawyer and collector of historical documents Uselma Clarke Smith.

Fanny had five other grandchildren in Canada through daughter Catharine Mitcheson Bagg.

2. For example, Mary donated the Forman papers, MS 0403. H. Furlong Baldwin Library., Maryland Center for History and Culture, https://mdhistory.libraryhost.com/repositories/2/resources/49

This article is also posted to https://writinguptheancestors.ca