The Webster dictionary gives the following definitions of sauna: A Finnish steam bath is a room in which steam is provided by water thrown on hot stones. The sauna is a small room or hut heated to around 80 degrees Celsius. It is used for bathing as well as for mental and physical relaxation.

There was a time, in the not too distant past when there were more saunas in Finland than there were cars.

*****

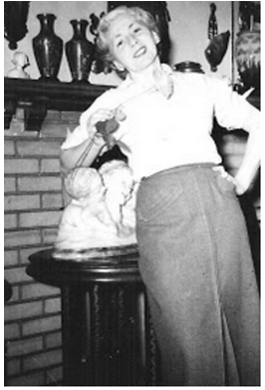

On a bright sunny morning in southern California, the week before Christmas 1967 at the age of eighty-one, Ida Susanna decided to enjoy what had long ago become a ritual. The sauna had been heated. It was ready. She and several family members were enjoying the heat, steam, warmth and comfort of the sauna when suddenly Ida began feeling uneasy and within a short time she succumbed on the spot, right then and there! Her last breath was in her beloved sauna, a Finnish tradition she had enjoyed throughout her life. Now, she had come full circle.

Ida Susanna Karhu drew her first breath and saw the light of day in a sauna on a cold morning in the dead of winter, March 12, 1886, in the rural village of Isokyro, on the banks of the River Kyro, in Western Finland, the Ostrobothnia Region, where St. Laurence Church built in 1304 still stands to this day, twenty minutes from Vaasa, Finland near the Gulf of Bothnia.

As a youngster, she played with friends and watched her younger brother and sister. She went to school and dreamed of a new life in a far-away country where her father was waiting for the family. Johan had left for America several months earlier. At that time the United States was actively recruiting immigrants. He was up to the challenge.

The time had finally come for the family to be reunited. In early spring of 1896 Ida, her mother, Sanna, 42, her brother Jakko and sister Lisa Whilemena, had taken all the necessary steps toward making their way to ‘Amerika’. The Finnish passport containing all four names was in order, having undergone rigorous scrutiny prior to being issued. Four tickets were purchased at the cost of FIM 138 per passenger. The date for departure had been set for May 16, 1896.

It must have been a harrowing thirteen-day voyage for Sanna, with the responsibility of three young children although Ida was able to help with the little ones. They made their way to Hango, Finland, on to Hull, England, aboard the SS Urania, then by train to Liverpool, England. The travellers then boarded the SS Lucania, a Cunard Liner, destination New York City with two thousand eager passengers. Some were either homesick or seasick or both.

They passed the Statue of Liberty as they approached Ellis Island on May 29, 1896, where the lengthy registration process began before they could go down the ‘stairway to freedom and a new life’.

There were new horizons for the ten year Ida, and her family as they made their way to Ashtabula, Ohio. She went to school, was a diligent student who learned to read and write in English while maintaining her Finnish language and heritage.*

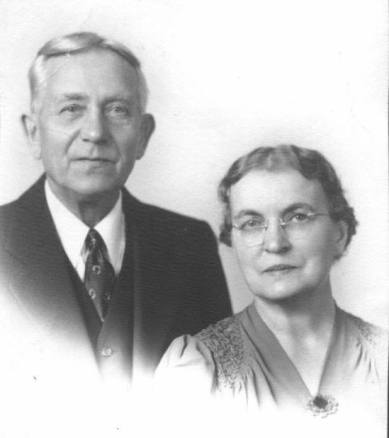

In 1903 at the age of sixteen, she married a fellow Finn, nine years her senior, had nine children. Johan (John), blacksmith, provided for the family for forty years until he was fatally struck by a young fellow driving a forklift. After his passing Ida had several suitors. She remarried, however, her new husband, Herman Haapala died within several years.

Ida Susanna was a lady with sisu*, a Finnish word for perseverance, courage and determination. She married for the third time to a gentleman named Gust Gustafson and enjoyed a good numberof years living on a large dairy farm in Cook, Minnesota. For almost ten years they travelled., One summer they visited her son in Canada, and wintered in Florida.

Was she visiting or had she decided to leave Gust and the cold weather for sunnier climes? We may never know. She made her way to southern California where several of her children were living. It was there in the sauna that she passed away. She had come full circle.

She lived life to the fullest throughout those many years in “Amerika” her adopted country. She is buried beside her first love, her husband of forty years, Johan Hjalmar Lindell, in Edgewood Cemetery in Ashtabula, Ohio.

*Sisu is a Finnish term and when loosely translated into English signifies strength of will, determination, perseverance, and acting rationally in the face of adversity. However, the word is widely considered to lack a proper translation into any other language. Sisu has been described as being integral to understanding Finnish culture. The literal meaning is equivalent in English to “having guts”, and the word derives from sisus, which means something inner or interior. However sisu is defined by a long-term element in it; it is not momentary courage, but the ability to sustain an action against the odds. Deciding on a course of action and then sticking to that decision against repeated failures is sisu.

.

![DSC06981[1]](https://genealogyensemble.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/dsc069811.jpg?w=474)