On September 15, 1943 Police Inspector James Scales stopped my father, Edward McHugh, on the road between Easingwold and Tholthorpe. It was the middle of WWII and my father was probably in a hurry to get back to the RCAF base in Tholthorpe, Yorkshire, England. As he was part of the maintenance ground crew of RCAF Iroquois Sqaudron 431, he may have had to get up early to prepare the aircraft for an early morning sortie.

Officer Scales stopped my dad while he was riding a bicycle in the dark. He had left Easingwold, a small village about a half hour bicycle ride from the base. More specifically, it was 10:15 p.m. I have the Summons that he received to report to the Court of Summary Jurisdiction in Easingwold.1

Dad was riding a “certain pedal bicycle” during the hours of darkness. He had unlawfully failed to attach the “obligatory lights” in conformance with the Lighting (Restrictions) Order, 1940.2

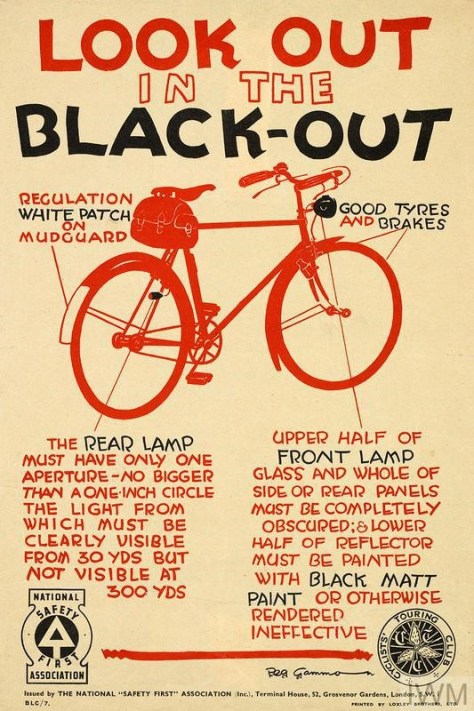

Great Britain, together with France, declared war on Nazi Germany on September 3, 1939.3 By January 1940, the Lighting (Restrictions) Order established a country-wide blackout during the hours of darkness.4 This restricted and forbade public lighting in towns. It required that street lamps be dimmed and that business and private residences black out their windows with blackout curtains so that light could not seep out. It also provided specifications for dimming the lights of motor vehicles and bicycles.5

Here is a poster that gives instructions on how to outfit a bicycle so that the lights are dimmed and facing the ground.6

My father would have known that the blackout was important and all his life he scrupulously followed the law. So he was not stopped because he didn’t care about the blackout. He was stopped because he didn’t have any lights at all.7

Once Britain imposed a country wide blackout through the Lighting (Restrictions) Order, car accidents increased and pedestrian fatalities doubled.8 Citizens were discouraged from nights out at the pub and were told to carry a newspaper or a white handkerchief so that they could be seen.9 Police Inspector Scales had decided to impose the letter of the law.10

I like to imagine that my dad had cycled into Easingwold for an evening out at the pub for a pint and a game of darts. He learned to play darts during the war and he continued to enjoy the game his whole life. Bicycles were used on the base, so I assume that he borrowed one of them.11

In any event, while he must have been frustrated at being summoned to court for failing to have a light on the bicycle, it does seem a little dangerous to be travelling on a country road with no lights during a total blackout. But surely a smaller risk than fighting in a war that lasted five years.

- Summons to Edward McHugh, LAC, No. R. 6278 of 431 Squadron, RCAF Station Tholthorpe dated September 21, 1943, in author’s possession.

- Ibid.

- Wikipedia web site, “Declarations of war during World War II,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Declarations_of_war_during_World_War_II, accessed April 22, 2018.

- Wiggam, Marc Patrick, The Blackout in Britain and Germany in World War II, Doctoral thesis, University of Exeter, March 2011, page 107.

- The Guardian, online edition, “Life during the blackout,” November 1, 2009, https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2009/nov/01/blackout-britain-wartime, accessed April 22, 2018.

- Used with the kind permission of the Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents. rospa.com.

- Summons to Edward McHugh, LAC, No. R. 6278 of 431 Squadron, RCAF Station Tholthorpe dated September 21, 1943, in author’s possession.

- Spartacus Educational web site, Blackout World War 2, http://spartacus-educational.com/2WWblackout.htm, accessed April 22, 2018.

- The Guardian, online edition, “Life during the blackout,” November 1, 2009, https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2009/nov/01/blackout-britain-wartime, accessed April 22, 2018.

- Summons to Edward McHugh, LAC, No. R. 6278 of 431 Squadron, RCAF Station Tholthorpe dated September 21, 1943, in author’s possession.

- Joost, Mathias (Major), The unsung heroes of the Battle of Britain: The ground crew of No. 1 (RCAF) Squadron, September 11, 2017, Royal Canadian Air Force web site, http://www.rcaf-arc.forces.gc.ca/en/article-template-standard.page?doc=the-unsung-heroes-of-the-battle-of-britain-the-groundcrew-of-no-1-rcaf-squadron/idw3fd9t, accessed April 22, 2018.